Click here for the latest version of our 50-state maps showing the status of legislation to roll back or strengthen child labor protections.

Early this year, we detailed the continued state legislative attacks on child labor protections as well as bills to strengthen child labor standards. Despite the recent rise of child labor violations and several high-profile child labor cases, the industry-backed effort to roll back child labor protections state by state continued, with state bills targeting youth work permits, work hours, and protections from hazardous work. At the same time, many state legislators have recognized the urgent need to strengthen standards and have instead proposed legislation to improve state child labor laws and their enforcement.

Now that most state legislative sessions have ended for the year, here is a look back at how these child labor proposals fared.

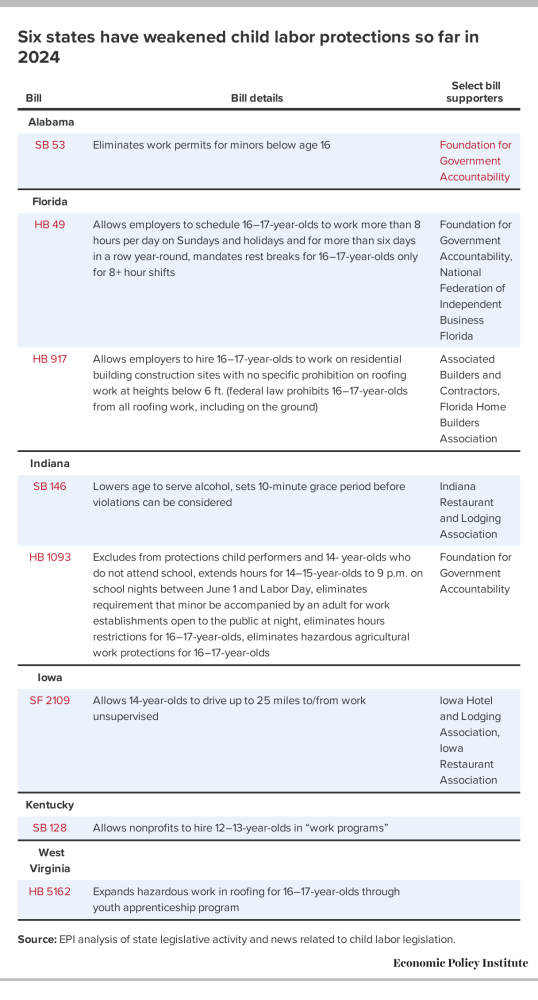

Six states have rolled back child labor protections in 2024

Alabama, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, and West Virginia all enacted legislation to weaken child labor protections this year. The content of these bills spanned the issues of youth work permits, youth driving, minimum work ages, maximum work hours, rest break protections, and hazardous work protections for minors (see Table 1). In Louisiana, a bill to eliminate rest breaks for minor workers has been passed and awaits the governor’s signature. In many cases, the bills targeted areas of state law that were stronger than federal standards, or areas where there are no federal mandates (such as youth work permits). Like last year, supporters for these bills included the Florida-based, right-wing think tank—Foundation for Government Accountability (FGA)—as well as lobbying groups representing the restaurant, hospitality, grocery, and construction industries.

Florida and Indiana enacted two rollback bills each. Both states took aim at hours protections for 16- and 17-year-olds, an area of the law on which the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)—the federal law which articulates most federal child labor protections—is silent (the FLSA passed 86 years ago when fewer than half of students completed high school). Both states also weakened restrictions on hazardous work for teens. And, in both states, very extreme bills were heavily amended between introduction and final passage due to sustained advocacy by in-state groups, such as the Florida Policy Institute and Indiana Community Action Poverty Institute.

- In Florida, SB 460 would have allowed employers to hire 16- and 17-year-olds for work on dangerous commercial and residential construction sites, including in one of the most dangerous occupations (roofing)—in violation of federal law. After advocates sounded the alarm about this harmful provision, the final bill (HB 917) allows employers to hire 16-and 17-year-olds only in residential building construction, only at heights under six feet, and only for work that does not violate federal law. HB 49 would have allowed employers to schedule 16- and 17-year-olds for unlimited hours, overnight, and without breaks during the school year. However, after vocal opposition, some of the bill’s most harmful provisions were amended. The final bill preserves nightwork protections, a cap on hours per day and per week, a prohibition on work during school hours, and rest breaks for 16- and 17-year-olds.1

- In Indiana, SB 146 initially proposed giving employers complete immunity in the case of injury or death of a minor employed in a work-based learning program. That disturbing provision was scrapped in response to significant opposition.2 Unfortunately, Indiana’s other rollback bill (HB 1093), which eliminates many protections for 16- and 17-year-olds among other harmful provisions, was enacted and represents one of the most harmful bills signed into law this year.

Kentucky, West Virginia, and Iowa each considered two child labor rollback bills, and in all three states, one bill was enacted and the other failed.

- In Kentucky, state legislators succeeded in passing a bill (SB 128) to allow nonprofit employers to hire children as young as age 12 (the minimum age for most employment under federal law is 14, but nonprofits are often exempt from FLSA coverage). However, an even more harmful bill in Kentucky was defeated. The version of HB 255 under serious consideration would have eliminated all hours protections for 16- and 17-year-olds, allowing employers to schedule these teens for unlimited hours per day or per week, including on school days. The bill also would have allowed employers to hire 14- and 15-year-olds for hazardous jobs prohibited for this age group under federal hazardous occupation orders. Fortunately, this harmful bill failed after groups like the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, the Kentucky Labor Cabinet, and their union allies organized in opposition to the bill.

- West Virginia lawmakers passed a bill to expand hazardous work for teens through a youth apprenticeship program. While the language was modified to encourage compliance with federal law in response to advocate concerns, the final bill nonetheless contains unclear language likely to confuse both employers and workers and weakens existing hazardous work standards in the state. Though youth apprentices are still protected by federal law, the roofing exemption stipulated in the bill does not exactly match federal language designed to protect youth apprentices from exposure to hazardous work; moreover, the small subset of youth hired by employers not covered by the FLSA will no longer be protected by state law. Fortunately, another bill in West Virginia (HB 5159), which proposed eliminating youth work permits for 14- and 15-year-olds, was defeated after advocates like the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy raised awareness about the importance of youth work permits in preventing violations and aiding in enforcement of child labor laws.

- On the heels of a disastrous child labor rollback bill enacted last year, Iowa signed into law an additional bill to allow 14-year-olds to obtain a special permit to drive unaccompanied 25 miles to and from work. The bill, which further weakens Iowa’s already weak commitment to the graduated driver licensing standards that have been shown to significantly reduce driving-related fatalities, will put even more teens at risk of traffic fatalities in service of employers’ access to low-wage labor. Iowa also considered, but did not pass, a bill to further weaken child labor standards in child care settings by expanding on a bill passed in 2022 (HF 2198). The 2024 bill would have allowed 16-year-olds to be charged with the care of four infants, seven toddlers, or 10 three-year-olds without direct supervision.

Further, Alabama ended youth work permits for 14- and 15-year-olds. And, in Wisconsin, a bill to eliminate youth work permits for 14- and 15-year-olds passed both chambers of the legislature but was vetoed by Governor Tony Evers in a public display of support for workers and opposition to ongoing attempts to weaken child labor protections in the state.3

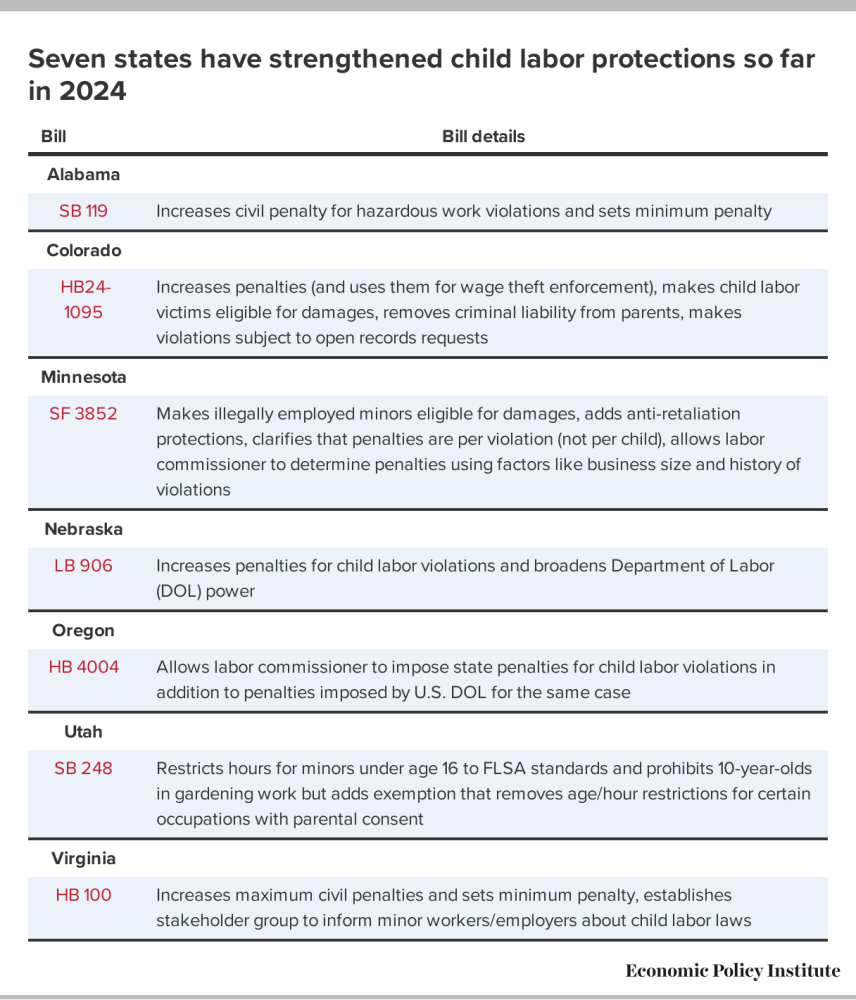

Seven states have strengthened child labor protections in 2024

However, in response to sustained attacks on child labor protections, lawmakers in an increasing number of states introduced legislation to strengthen protections for children in the workplace and improve enforcement of child labor laws. Lawmakers in 20 states and the District of Columbia introduced such bills in 2024, and governors in seven states signed stronger protections into law: Alabama, Colorado, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, Utah, and Virginia (see Table 2). Meanwhile, Illinois passed a comprehensive bill to strengthen child labor protections, but it has not yet been sent to Governor JB Pritzker for his approval.

Alabama, Colorado, Nebraska, Oregon, and Virginia passed legislation increasing penalties for child labor violations or, in the case of Oregon, allowing the state to pursue penalties against an employer in addition to penalties imposed by the federal Department of Labor (DOL). And in Utah, the same month that the U.S. DOL fined a Utah Baskin Robbins franchisee for violating federal law after erroneously following weaker state laws, the Utah legislature passed a bill bringing state child labor laws in line with the FLSA. For instance, previous Utah law allowed employers to schedule 14-year-olds to work four hours on a school day and until 9:30 p.m. on a school night and did not set maximum hours guidelines during the school week. Under federal law, employers can schedule minors under age 16 to work a maximum of three hours per day and 18 hours per week in a school week and until 7 p.m. during the school year.

States like Colorado, Illinois, and Minnesota have gone further, passing more comprehensive measures that reform and modernize multiple aspects of child labor law. In Illinois, lawmakers updated the youth work permit process, the list of prohibited hazardous occupations, and the penalties that can be levied against employers who break the law. The youth work permit process plays an important role in maintaining informed consent from families about a child’s work activities, ensuring that employment is safe and age-appropriate, and aiding enforcement. There is also evidence that youth work permits prevent violations from happening in the first place by serving as an early warning system for potentially harmful employment. A new study by researchers at the University of Maryland found that states mandating youth work permits saw an average of 16.9% fewer child labor violations and 43.4% fewer minors involved in child labor violations between 2008 and 2020. At a time when many states are seeking to eliminate this system, states seeking instead to improve them should look to Illinois for guidance.

Colorado has led the way in legislation to incentivize reporting of violations and provide remediation to children harmed by illegal employment practices. Last year, the state enacted a law that allows the families or guardians of children who are injured or killed on the job due to illegal work practices to pursue legal claims against their employer (in addition to filing workers’ compensation claims). Colorado followed that bill with a more comprehensive proposal this year to:

- Increase both civil monetary penalties and criminal penalties for child labor violations.

- Make victims eligible for statutory damages (in recognition that penalties are remitted to the state and do not benefit victims directly).

- Establish anti-retaliation protections for those who report violations, remove statutory language that allows parents to be held criminally liable for permitting their child to work in violation of the law.

- Require the state labor agency to make violations data public (with personally identifiable information redacted). Often, victims of child labor do not report violations because of valid fears of employer retaliation and concerns that doing so will not benefit them.

The Colorado law’s joint effort to incentivize reporting through victim remediation and deter violations of the law through increased penalties is relatively rare among proactive child labor bills4 but is a model that more state legislators should emulate.

What’s next for state child labor legislation?

Next year, we can expect to see continued attacks on state laws that exceed the floor of limited child labor standards in the FLSA. However, in response to the nationwide crisis of increasing child labor violations, we can also expect to see additional proposals to deter violations from happening in the first place (through enhanced work permits and increased employer liability) and to incentivize reporting of violations when they do occur (by protecting reporters and directing remediation and services to victims). There are a variety of policy approaches state lawmakers can take, and proposals that address multiple areas of the law at once are preferable. States should also consider eliminating discriminatory youth subminimum wages and addressing loopholes in agricultural employment that leave children unprotected from dangerous and exploitative working conditions on farms across the country.

Notes

1. However, HB 49 added caveats to these standards for 16–17-year-olds. The eight-hour-per-day cap now applies only to weekdays and Saturday, parents can waive the 30-hour-per-week cap, and teens are eligible for rest breaks only during shifts of eight hours or more (instead of after four hours).

2. A similar provision was proposed last year in Iowa (SF 542). The provision was eventually scrapped but was replaced by a provision that limits employer liability for injuries sustained by minors in work-based learning programs.

3. Wisconsin eliminated work permits for 16- and 17-year-olds in 2017 under Governor Scott Walker. In 2021, the legislature passed a rollback of work hours protections for minors under age 16, but Governor Evers vetoed it. And, in 2023, Wisconsin legislators proposed lowering the alcohol service age to 14—the lowest nationwide—but the bill failed.

4. As far as the author is aware, other than IL SB 3646, only one other recent state legislative proposal aims to both incentivize reporting through victim remediation and deter violation through increased penalties. MI 2023 HB 4932 increases penalties, adds anti-retaliation protections, and allows child labor victims to sue for damages.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.

Spread the word