Democrats are focused on one thing for the next four months: preventing the rise of Donald Trump, J.D. Vance, the Republican Party, and everything the MAGA movement stands for. The New Popular Front spirit of anti-fascist unity across the left and center has made its way to the United States, and not a moment too soon.

In that context, beginning to think about what a Harris administration would actually do is arguably premature. But that being said … yeah, what would a Harris administration actually do?

No matter how motivated a given voter may be to oppose Donald Trump, it’s still reasonable for them to wonder what they’ll actually get if they vote for Kamala Harris. The plutocrat class—who are certainly no hard-liners against Trump—has been asking this question too. In a rather stunning show of attempted bribery, LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, who has donated $7 million to a Harris-aligned superPAC, went on television to demand Harris replace Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan once elected. Media mogul and Expedia chairman Barry Diller later seconded the call, as did Barry Sternlicht, head of real estate company Starwood Capital. All three of these corporate titans run or are on the boards of companies being actively investigated by the FTC.

Unnamed “outside advisers to the campaign” (probably some lobbyists gossiping to a gullible reporter) claim Harris is considering a “reset” of regulation of the cryptocurrency racket—sorry, “industry.” And Wall Street ghouls like austerity fetishist Peter Orszag, housing mogul Jonathan Gray (whose Trumpian boss once compared tax hikes on the rich to Hitler’s invasion of Poland), and BigLaw fixer Brad Karp are opening their pocketbooks and working the phones of their press contacts. Karp in particular reportedly led a high-dollar Zoom fundraiser for Harris focused on “how Wall Street could best support a Harris ticket.”

At least rhetorically, Harris doesn’t seem to be biting on economic retrenchment. In her first major speech on the economy, Harris explicitly recommitted to passing the pro-labor PRO Act. In a later speech, she declared she’d “cap unfair rent increases” and attack junk fees on day one, as part of a plan to “take on price gouging and bring down costs.” Most of the tools for doing so run through Khan at the FTC, and Rohit Chopra at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, another regulator much reviled by big money donors. As the Prospect’s David Dayen has noted, Khan, Chopra, and other progressive appointees have provided the Biden-Harris administration with most of its brag points on the campaign trail this year. (Chopra actually brought Khan into the FTC when he was a commissioner there.)

This is all Biden’s economic policy agenda, and Harris is running as Biden’s successor. But of course, campaign rhetoric only means so much, especially when it’s this vague. Harris’ welcome declaration that she’d sign the PRO Act is one of the few hard commitments she’s made so far. Huge swaths of economic policy remain unaddressed: financial regulation, merger approval, spending and taxes, and more.

Economics reporters have asked former Harris aides and associates about her views over the last few weeks. The most consistent theme from their comments is that she is less concerned with macroeconomic frameworks than the human impact of policy: “Do these policies give people more freedom, choices, and ultimately autonomy over their own lives?” in the words of former Harris aide Rohini Kosoglu.

With deep respect to Harris and her staff, this sounds like the kind of thing an aide politely says about their boss who honestly just isn’t that interested in economic policy. And if so, that’s fine! Everyone finds some issues more exciting than others, and Harris has deep, demonstrated commitments on many of the most important domains in American life today, especially abortion, the power of the courts, and pro-democracy structural reforms. If she doesn’t thrill to the latest quarterly GDP data, that makes her like 99 percent of the public.

It also makes her like her current boss. Though his Senate career was marked by carrying water for his home-state credit card industry, it turned out Joe Biden didn’t have many strong personal priors on economic policy, so he generally just planted his flag in the exact median of Democratic Party opinion. That median has shifted substantially leftward in recent years, so he could be persuaded on some topics through well-deployed leverage and well-tailored arguments.

But if the president is not ideological on economics, then their economic advisers and appointees are that much more important. If you don’t have a strongly-held mental model of the economy, then the mental models of whoever surrounds you—no matter how accurate, and no matter what values they reflect—effectively become yours. In the words of Joan Robinson, “The purpose of studying economics is not to acquire a set of ready-made answers to economic questions, but to learn how to avoid being deceived by economists.”

Historically, high-dollar fundraisers like Karp’s are where politicians get taken in by those deceptions. They’re where a wealthy and generous host can introduce a candidate to the intelligent, well-spoken, numerically literate young person from Big Tech, BigLaw, or Wall Street who just so happens to be interested in a policy job.

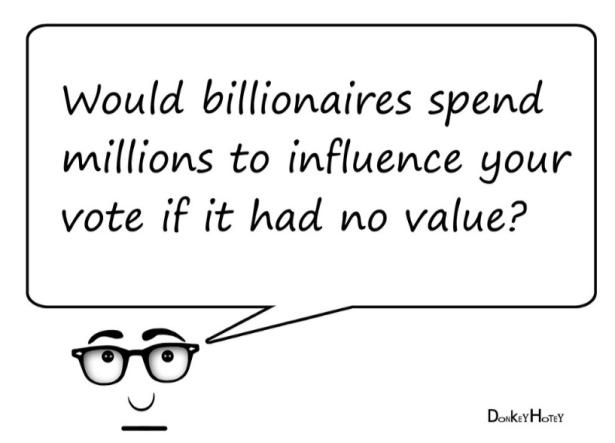

Like Biden, Harris doesn’t appear to have personal qualms with making friendly with ultra-rich donors. But the public definitely wants candidates who aren’t bought and paid for: 80 percent of Democratic-leaning voters say large donors have too much influence in politics, and 76 percent say there should be hard limits on political spending. Republican-leaning voters poll about the same. Opposition to big money is perhaps the last bipartisan issue in U.S. politics.

In this context, big donors going on TV and explicitly asking the candidate they showered with money for personnel decisions seems like a misstep. Hoffman’s pathetic excuse that he was just talking about Khan as an expert and not a donor was treated with the skepticism it deserved, and just dug the hole deeper.

The public is showing Harris another path. In just over a week, she has shattered small-dollar fundraising records. She boasts a substantial $200 million war chest and over 170,000 volunteers. Moreover, 66 percent of her contributors were first-time donors. Her campaign has little fiscal need for high-dollar fundraisers at this point.

More generally, Harris clearly cares about crushing Trumpism, and ushering American democracy into a new, more inclusive and robust era. Refusing big money is a natural extension of that vision. Bringing the Supreme Court to heel without addressing any of the other ways billionaires have bought Washington would treat one particularly bad symptom, but not the disease.

Harris should certainly want to be at least as good as her predecessor on money in politics. Khan’s anti-monopoly agenda, Chopra’s crusade against junk fees, National Labor Relations Board General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo’s support for unions, and others also poll extraordinarily well, especially among young people. Throwing these effective, progressive regulators to the curb in favor of Wall Streeters and corporate hacks would be worse than “more of the same,” it would actively pull the Democratic Party further from the public’s preferences. All that Harris would get in exchange is some more short-term money for an already well-resourced campaign.

As she prepares to lay out an actual agenda in the coming weeks, Harris should recognize these risks. And progressives shouldn’t be afraid to remind her of hard lines against tossing out the most accomplished and brag-worthy appointees in the current administration. Over the past four years, the left has proven that a Democratic administration cannot safely ignore it. Harris has successfully jolted Democrats across the political spectrum into action. She shouldn’t risk demobilizing the young, diverse, working-class base just to grovel to billionaires.

Spread the word