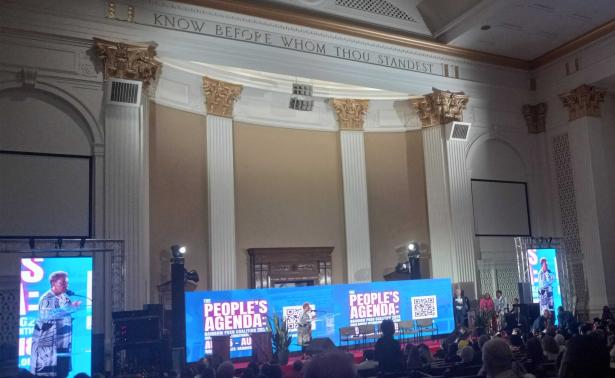

On the night before the start of the Democratic National Convention, while dozens of delegates from Maryland were gathering at an Irish pub along the Chicago River for their welcome party, I was on the South Side of Chicago, in the ornate but crumbling headquarters of the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, for a tribute to the Rev. Jesse Jackson.

Jackson was also hailed the next night on the convention stage, but this Sunday evening event, while far bigger and impossibly long, seemed more intimate, more heartfelt, and as much a call to action as a celebration of the elderly and ailing icon of the civil rights movement and pioneering presidential candidate.

It was also incredibly stirring, and moving, but also depressing in a way. The dilapidated Rainbow PUSH headquarters, once a synagogue, felt a little like a metaphor. I heard rhetoric that night — and political movements discussed and recalled in a certain way — that I hadn’t heard in 40 or 50 years. I even saw a gray-haired woman wearing a T-shirt for “The War at Home,” a documentary about the 1960s anti-war movement in Madison, Wisconsin, that faded into obscurity after its release 45 years ago.

Jackson was one of the great orators in American history, whose best phrases, like “Keep hope alive!” are still very much a part of the American political lexicon. Now 82 and fighting Parkinson’s, he uses a wheelchair and is unable to speak beyond a mumble. But he sat in the front row of the Rainbow PUSH auditorium during the tribute, and dozens of people stopped by to say hello.

The night got me thinking about the through-line between Jackson and Black political leaders today, including Gov. Wes Moore (D), Prince George’s County Executive Angela Alsobrooks (D) and other Marylanders.

I also wondered why there was no one that I recognized there from Maryland, other than Larry Cohen, the retired leader of the Communications Workers of America, who is white, and has long been associated with the far left of the Democratic Party (U.S. Rep. Jamie Raskin, a former general counsel for the National Rainbow Coalition, a predecessor to Rainbow PUSH, was supposed to speak, but had a last-minute scheduling conflict).

It was said often, on both nights in Chicago, that there wouldn’t be a Kamala Harris, there wouldn’t be a Barack Obama, without Jesse Jackson, and in some respects, that’s true. Jackson made it plausible for voters to imagine a legitimate Black presidential candidate, even though his was much more of a protest candidacy than Obama’s or Harris’.

Just as significant, Jackson challenged party rules and inveighed against the growing influence of corporate interests in the Democratic Party. (I cannot think of him referring to the old Democratic Leadership Council, which sought to move the party closer to the political center in the 1980s and ’90s, as “Democrats for the Leisure Class,” without laughing.)

The former literally made it easier for Obama to defeat Hillary Clinton for the White House nomination in 2008, because it loosened the grip of party leaders on the presidential nominating process. Who can forget the image of Jackson shedding tears on the night Obama was elected president, overwhelmed by the fruits of his labors being realized to a degree, at the campaign’s giant celebration in Chicago’s Grant Park?

But Jackson’s push to move the party away from corporate interests? That seems to have run aground.

Jackson ran insurgent campaigns in 1984 and 1988, and the only thing that has come close since are the presidential runs of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020.

Sanders, one of dozens of speakers at Rainbow PUSH that night, said as much, noting that Jackson was the first prominent political leader to publicly call health care a human right.

“That’s where Jesse Jackson was 30 years before I was,” Sanders said. “Thirty years ago, he was talking about profoundly changing our health care system.”

A stained sign at the Rainbow PUSH Coalition headquarters in Chicago. Photo by Josh Kurtz.

Sanders added: “I happen to believe that Jesse Jackson is one of the most significant political leaders in this country in the last 100 years.”

Obama was initially the underdog against Clinton in 2008 and perceived as slightly more progressive. But he was, and Harris is, a conventional politician treading a conventional political path.

You can look at what Jackson was espousing during his presidential campaigns and throughout his career and say, yes, the Democratic Party has moved slightly to the left over the years and is now embracing calls for expanding health care access, eradicating poverty, and more equity and inclusiveness in every aspect of society. But that embrace has been slow, and progress incremental.

At the same time, many of the rights Jackson fought for over the decades are being eroded by Republicans and federal courts. The long, moral arc of history may bend toward justice, as Martin Luther King Jr. once said, but it sure runs into a lot of roadblocks.

At the Democratic convention in Chicago, Maryland had the most diverse delegation in the country, and that’s worth celebrating. Marylanders can point with pride to the success of Moore and Alsobrooks and dozens of rising political leaders in the General Assembly and in local governments and think, part of Jackson’s dream is being fulfilled.

Jackson during his campaigns was a little like the poor kid pressing his nose against the window watching the swells at a debutante ball. Now Black political leaders often sit at the head of the table. And that’s progress by any measure.

But these too are largely conventional politicians treading conventional paths, preaching action but exercising caution, a little too comfortable cozying up to the big-moneyed interests that still dominate our politics, especially in Annapolis.

That convention welcome party at the Irish pub was sponsored by a Baltimore/Annapolis lobbying firm, a utility contractor, and a Prince George’s County development company. A lobbying firm and a health care giant sponsored two of the Maryland delegation’s breakfasts. Spend any time in Annapolis during a General Assembly session and you know how depressingly easy it is for special interests to sway a debate.

At the Rainbow PUSH headquarters, Tennessee state Rep. Justin Jones (D), who faced expulsion from the legislature because he protested for gun control on the House floor, was given a hero’s welcome.

In Annapolis, the few legislators who most vocally embrace Jackson’s most radical positions and tactics — on economic equality, on making the rich and corporations pay their fair share, on Palestinian statehood, on tenants’ rights, on workers’ rights, on Medicare-for-all, on aggressive climate action — are often marginalized, if not outright ostracized.

As U.S. Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), a forceful progressive despite representing Silicon Valley, said in Chicago, “We can’t celebrate Rev. Jackson without listening to what Rev. Jackson is calling on us to do.”

Founding Editor Josh Kurtz is a veteran chronicler of Maryland politics and government. He began covering the State House in 1995 for The Gazette newspapers, and has been writing about state and local politics ever since. He was an editor at Roll Call, the Capitol Hill newspaper, for eight years, and for eight years was the editor of E&E Daily, which covers energy and environmental policy on Capitol Hill.

Maryland Matters is a trusted nonprofit and nonpartisan news site. We are not the arm of a profit-seeking corporation. Nor do we have a paywall — we want to keep our work open to as many people as possible. So we rely on the generosity of individuals and foundations to fund our work.

Years ago, healthy competition for news out of Annapolis and across the state produced robust coverage. But the media landscape has changed. Newspapers have closed. Suburban bureaus have shut down. Reporting staffs have shrunk. Coverage of state and local news has all but disappeared. Maryland Matters seeks to fill the void with original reporting and commentary.

Spread the word