Some 45,000 years ago, a tiny group of people — fewer than 1,000, all told — wandered the icy northern fringes of Europe. Across thousands of miles of tundra, they hunted woolly rhinoceros and other big game. Their skin was most likely dark. To keep warm in the bone-chilling temperatures, they probably wore the hides and furs of the animals they killed.

These hardy people of the Ice Age, known as the LRJ culture, left behind distinctive stone tools and their own remains in caves scattered across Europe. On Thursday, researchers revealed the genomes of seven LRJ individuals from fossilized bones found in Germany and the Czech Republic — the oldest genetic specimens of modern humans yet found.

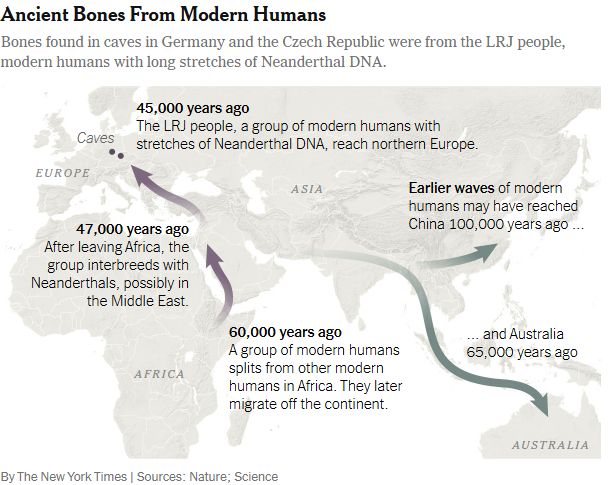

It turns out the LRJ people were part of the early human expansion from Africa to other parts of the world. But theirs was a surprisingly recent migration.

The common ancestors of the LRJ people and today’s non-Africans lived about 47,000 years ago. In contrast, studies of remains in Australia suggest that modern humans reached that continent 65,000 years ago. And in China, researchers have found what look like the bones of modern humans dating back 100,000 years.

The huge gap between those ages could change our understanding about how humans spread across the world. If the ancestors of today’s non-Africans didn’t sweep across other continents until 47,000 years ago, then those older sites must have been occupied by earlier waves of humans who died off without passing down their DNA to the people now living in places like China and Australia.

“They cannot be part of the genetic diversity that’s present outside Africa,” said Johannes Krause, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and an author of the new study.

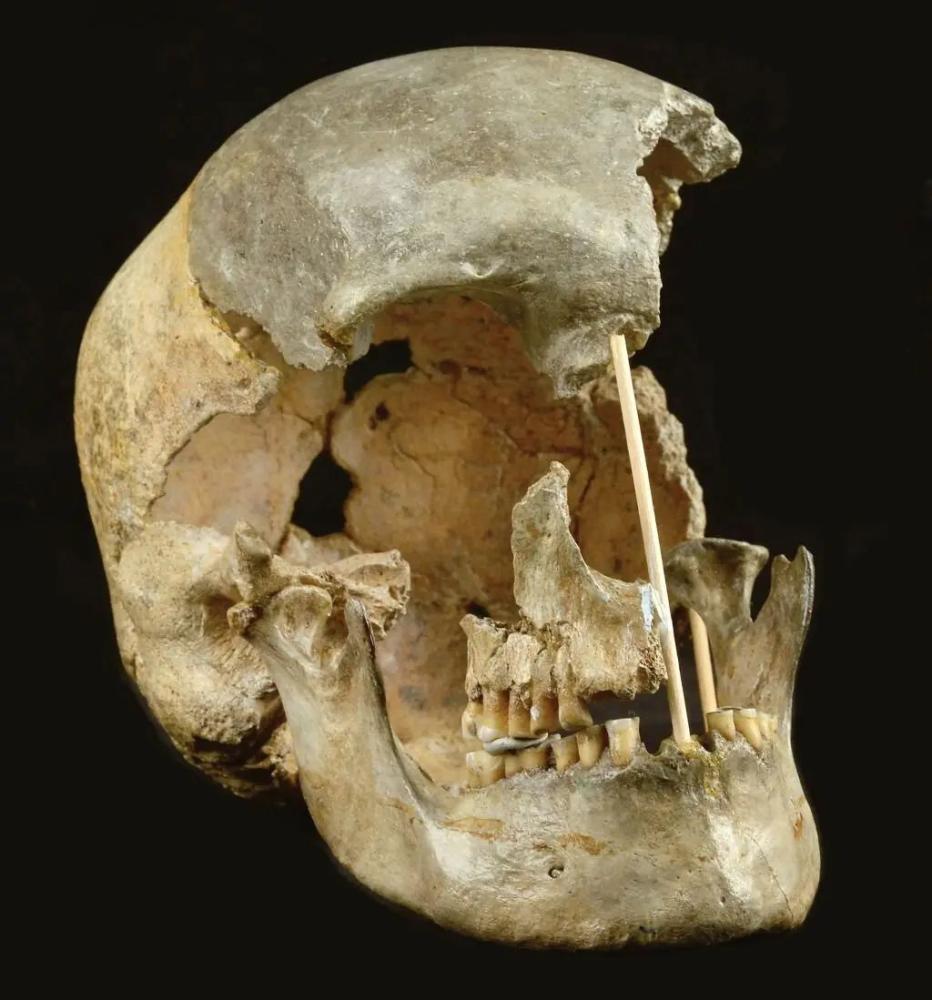

The newly discovered genomes come from fossils that have baffled scientists for decades. In 1950, archaeologists digging in a cave in what is now the Czech Republic found the skull of an ancient woman. They could not determine its age, however. They found stone tools at the site, known as Zlatý kůň, but the tools were not distinctive enough to link the woman to any particular cultural group.

A few years ago, Max Planck researchers managed to extract some DNA from the skull. A preliminary analysis hinted that the woman belonged to an ancient branch of humans.

The Zlatý kůň skull, found in 1950 in what is now the Czech Republic. Credit...Marek Jantač

Meanwhile, another set of ancient bones arrived from a cave in Germany called Ranis, about 140 miles west of Zlatý kůň.

The Ranis remains were discovered more than a century ago. Archaeologists had concluded that they had all belonged to a single ancient culture, which they called the Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician, or LRJ for short. But they did not know much more. It wasn’t clear if the LRJ people were modern humans or Neanderthals, for example.

In 2016, a team of archaeologists went back into Ranis for a fresh look. Marcel Weiss, an archaeologist at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany, and his colleagues uncovered a new batch of fossils and tools and used 21st-century methods to analyze them. The fossils yielded a wealth of DNA — enough to reconstruct the genomes of six individuals.

They were all closely related to each other, including a mother and her daughter. The scientists also discovered that two of them were closely related to the Zlatý kůň woman.

“It’s the same group, the same extended family,” Dr. Krause said. “It could be that they knew each other.”

The researchers estimated that all seven sets of fossils were at least 45,000 years old. Their genomes are now bringing the LRJ people out of history’s shadow.

Their genetic similarity indicates that they belonged to a tiny population that only numbered a few hundred at any given time. And the close kinship between the six Ranis and single Zlatý kůň individuals suggests that the LRJ people wandered in small bands over vast distances, spending little time in any one place.

“If I were to go to New York and just take one person from the Bronx and then go over to Long Island and take another person from there, it would be unlikely that these two have a common ancestor within the last three generations,” said Kay Prüfer, a paleogeneticist at Max Planck and a co-author of the new study. “But, of course, we are talking about the deep past, when things were different.”

Dr. Prüfer and his colleagues found that the LRJ people lacked some key mutations found in living Europeans. They did not have the genes that produce pale skin, for example, which suggests that they had dark pigmentation, as their ancestors who emerged from Africa did.

The cave in the Czech Republic where the Zlatý kůň skull was found in 1950. Credit...Martin Frouz

The scientists also used the genomes to figure out where the LRJ people fit on the human family tree. Previous studies had established that human ancestors evolved for millions of years in Africa. About 600,000 years ago, the ancestors of Neanderthals split off on their own. They spread through the Middle East and established themselves across Europe and western Asia. Neanderthals endured for hundreds of thousands of years, disappearing from the fossil record about 40,000 years ago.

Modern humans remained longer in Africa before expanding to other continents. When they met Neanderthals, possibly in the Middle East, they interbred. Today, all humans around the world carry at least a trace of Neanderthal DNA.

While the broad outlines of this history are well established, scientists are still struggling to pin down the specifics. Estimates of when modern humans and Neanderthals first interbred have ranged from 54,000 years ago to 41,000 years ago, for example.

Dr. Krause and his colleagues discovered that, unlike living humans, the LRJ people had long stretches of Neanderthal DNA in their genomes. This suggests that relatively little time had passed since modern humans interbred with Neanderthals. Dr. Krause and his colleagues estimate that the interbreeding took place 1,000 to 2,500 years beforehand, or about 46,000 years ago.

In another study published Thursday, a second team of scientists reached a similar conclusion by surveying Neanderthal DNA in fossils and in living people.

“It was really fantastic to see a similar date,” said Priya Moorjani, a paleogeneticist at the University of California, Berkeley, and an author of the second study.

Independent scientists said that the new timing suggested that modern humans moved from the Middle East to the northern margins of Europe at a remarkable speed. “The time frame gets really tight,” said Pontus Skoglund, a paleogeneticist at the Francis Crick Institute in London.

Dr. Skoglund also said it would be strange for non-African ancestors to have arisen about 47,000 years ago while modern humans in Asia and Australia dated back 100,000 years. The sites in question could have been incorrectly dated, he said, or people could have reached Asia and Australia that long ago, only to die out.

He Yu, a paleogeneticist at Peking University in Beijing who was not involved in either study, said that the mystery wouldn’t be solved until scientists find DNA in some of the ancient Asian fossils.

“We still need early modern human genomes from Asia to really talk about Asia stories,” Dr. Yu said.

Carl Zimmer: I write the Origins column for The New York Times and cover news about science.

I report on life — from microbes at the bottom of the sea to high-flying migratory birds to aliens that may dwell on other planets. For my column, I focus on how life today got its start, including our own species. Along with covering basic science, I write stories about how biological discoveries evolve into medical applications, such as editing genes and tending to our microbiome.

I wrote my first story for The Times in 2004. In 2013 I became a columnist. I began my career in journalism at Discover Magazine, where I rose to senior editor. I went on to write articles for magazines including The Atlantic, Scientific American, Wired and Time.

I also write books about science. My next book is “Air-Borne: The Hidden History of the Life We Breathe,” to be published in February 2025. I am an adjunct professor at Yale’s Department of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, where I teach seminars on writing and biology lecture courses. I have also coauthored a textbook on evolutionary biology, now in its fourth edition.

My books and articles have earned a number of awards, including the National Academies Communication Award and the Stephen Jay Gould Prize, given out by the Society for the Study of Evolution. I have won fellowships from the Johns Simon Guggenheim Foundation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. During the Covid-19 pandemic, I contributed to the coverage that won The Times the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 2021. I am, to my knowledge, the only writer after whom both a species of tapeworm and an asteroid have been named.

I live with my wife in Connecticut, alongside salt marshes rife with snapping turtles.

Subscribe to the New York Times

Ask Ethan: Can a lumpy Universe explain dark energy?

Ethan Siegel

Starts With A Bang/Big Think

January 3, 2025

Spread the word