In pursuit of a climate-conscious diet, my poor body has been through hell.

In 2015, partly as a premise for a PBS Frontline documentary and partly for research on my book The Omega Principle, I ate fish and shellfish as my sole sources of animal protein for an entire year. I had fish cakes for breakfast, salmon sandwiches for lunch, and anchovy-sauce pasta for dinner. I had self-caught striped bass for a week, during which I ate every fricking part of that damn animal and even boiled down its bones for stock.

In an effort to cut costs (since the average piece of fish is typically at least 150 percent the cost of beef), I trolled the markets of Manhattan’s Chinatown for cheap mackerel and porgy and bought canned sardines by the pallet. When I got tired of it all, I comforted myself with the fact that fish, specifically wild fish, tend to carry a fraction of the carbon burden of landfood. By some measures, wild fish are 98 percent less carbon costly than beef.

But when it was all said and done, the experiment was a failure. Not only was it expensive and inconvenient to be fully pescatarian, but by the end my blood mercury was well above what my home state’s health department deems safe. This despite the fact that I generally ate the low-trophic fish and shellfish that are supposedly the lowest in environmental pollutants. And while most mercury leaves the blood somewhat quickly once the pollutant source is removed, I certainly didn’t want to throw my body in that kind of harm’s way again.

A few years later, I went even further.

I became a vegan.

Again, technically, it was a journalism gig that made me do it. The magazine Eating Well commissioned me to try a plant-based diet to address my high LDL cholesterol and blood pressure. I didn’t want to go on statins, and I’d read reams of material, most notably Dr. Michael Greger’s plant-based manifesto How Not to Die, that made the argument that vegetables would fix my health problems. What he didn’t discuss is that they might fix our little planet, too.

I became fluent in chickpea and cashew. Nutritional yeast swept across my kitchen counter like the sands of the Sahara. I pressed tofu until I was blue in the face. The result? Truly a much lower carbon footprint. And I did mark some health improvements. I lowered both my LDL cholesterol and my blood pressure slightly, but in the end, I still needed medication for both.

By far, the thing a vegan diet was most effective at accomplishing was alienating my friends and family. Dinner invitations dropped away because cooking for a vegan is a drag. Cooking for my family usually involved double meal prep, because my heavily carnivorous son was most definitely not onboard. Sure, I learned how to fashion mozzarella from cashews and tapioca starch, and I can now make a pretty good mushroom Bolognese. But as soon as the Eating Well article was filed, I decided I’d had enough soy to last a lifetime. I became regime-less.

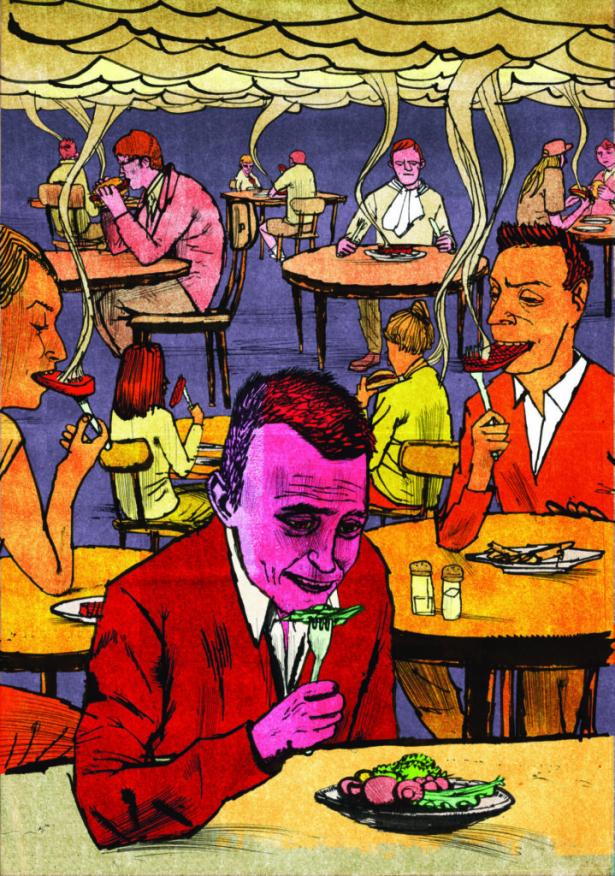

And lo, meat swept across the land. Red meat, white meat, land meat, sea meat. I ate it all. I continued to maintain a vegetable garden, but aside from my harvests of kale, collards and mesclun greens, I seldom bought or ate a vegetable. I gained back the twenty pounds I’d lost in the pesca-vega phases of my life. I became a practitioner—and a victim—of SAD: the unfortunate acronym for the so-called “Standard American Diet.” Crestor and Olmesartan pharmacologically protected my cardiology from most health effects. But the emotional part of my heart still bled. What was I doing to myself and the planet? Could meat, the Earth, and I somehow find a compromise?

This is the kind of rhetorical question that usually shows up at an essay’s midpoint and eventually leads to a laundry list of fixes that make the journalist’s editor feel like the assignment has been completed. But these sorts of laundry lists tend to carry very little water in real life. So, I hesitate to give said list before addressing the two key factors that I’ve come to believe squelch all attempts at betterment through diet: inertia and willpower.

How many times have we declared to ourselves that we will support regional farmers and shop exclusively at our local greenmarket, only to find ourselves vanquished by the cost and inconvenience and shuffling back to the Publix a week later? How many of us have said we’ll follow bestselling cookbook author Mark Bittman’s advice and do “VB6” (vegan before six p.m.), only to have that six become four, then two, then no time at all? The unavoidable problem of American humans is that we are creatures of habit. To change ourselves to be reliably more climate-friendly, we need to figure out which fixes might sync up with the ingrained habits we already have.

If we want to keep eating animals despite their carbon footprint, what is the absolute easiest and most convenient thing to do once we’ve gone to that temple of ease and convenience called the supermarket? It comes down to our choice of animals. No matter how animals are raised, whether in feedlots or pastures, organically or conventionally, each species that we eat has built-in qualities and limitations. Cows are big and relatively slow to mature, with a biological necessity to off-gas all the fermenting going on in their guts through their fronts and backs. Tweak all you like, but beef will remain in the high double and even triple digits of pounds of greenhouse gasses emitted for every pound of meat on the plate.

Chickens, meanwhile, are small, extremely feed efficient, reach maturity in a matter of weeks, and emit much less methane. Again, tweak all you want, but a cow costs the environment around 100 pounds of greenhouse gasses per pound of flesh, while your average chicken adds to the atmosphere only about six pounds.

What if I eat cow products like cheese instead of the cow itself? Sorry, the chicken still wins handily. At thirteen pounds of carbon emissions per pound of food on the plate, cheese prices out at around double the climate cost of chicken. In fact, no other landfood meat can beat the chicken, except, I guess, edible insects. Are you going to eat grasshoppers? I’ll pass.

At sea, clear choices also exist. Any supermarket fish counter has the equivalents of cows and chickens. The cow of the sea is, sad to say, shrimp. Sad because shrimp is by far America’s favorite seafood; we eat as much shrimp as the next most popular American seafood choices, salmon and canned tuna, combined. The reasons for shrimp’s high emissions burden are manifold. Trawling, the most common way of catching wild shrimp, is fuel intensive. In their farmed form, shrimp have led to the clearing of millions of acres of carbon sequestering mangrove trees in Southeast Asia and Central America. So, at thirteen pounds of carbon emissions per pound of shrimp (double that of chicken), the less of these crustaceans in our diet, the better.

What, then, is the ocean equivalent of the chicken? Ladies and gentlemen, I give you the mussel. Farmed mussels, perhaps the most carbon efficient animal protein on the planet, can be brought to market for the carbon equivalent of 0.6 pounds of carbon for every pound of mussel meat on the plate. With an average retail price of about five dollars a pound, the price is also right. And if you cannot stomach mussels (as many can’t), pretty much every other wild fish you can find in your seafood counter is still better than almost any landfood meat. That Alaska pollock in your Filet-o-Fish, for example, prices out at only 1.2 pounds of carbon per pound of fish.

Are there ways we can be even better than choosing chicken over beef and mussels over shrimp? Of course there are. One needn’t be a strict vegan to rotate in one vegetable-forward meal a week. And if you’re doing regular cardio workouts (as you should be), having one of those cardio workouts be a bike ride to the supermarket instead of a car ride can cut your carbon footprint for the day by more than any dietary choice.

My point is, that to improve our relationship with the planet, we don’t need to put ourselves through hell. A subtle, consistent change that we can maintain over many years is far more impactful than whipsawing between this extreme change and that. If you want to be vegetarian or vegan because you like that kind of food, great. But if you’re like me (and the vast majority of Americans) and don’t like being shackled to a regime or having your wallet pummeled at the cash register, there are four magic words that nearly always make your climate footprint a little smaller:

“I’ll have the chicken.”

Paul Greenberg is the author of seven books, including the James Beard Award–winning Four Fish and, most recently, A Third Term.

Spread the word