Economic Policy That Doesn't Confront the Rise in Inequality Head-On Will Do Nothing to Help the Vast Majority of American Families

In Progressive redistribution without guilt, EPI Research and Policy Director Josh Bivens explains why income growth for the bottom 90 percent will continue to disappoint unless policymakers put fighting the rise of inequality at the top of their agenda. Bivens argues that the rise in inequality in recent decades has been essentially zero-sum, with gains at the top of the distribution coming almost directly from gains at the bottom and middle. The zero-sum character of the rise in inequality means that policies aimed at progressively redistributing income can benefit the vast majority of working people without harming overall economic growth.

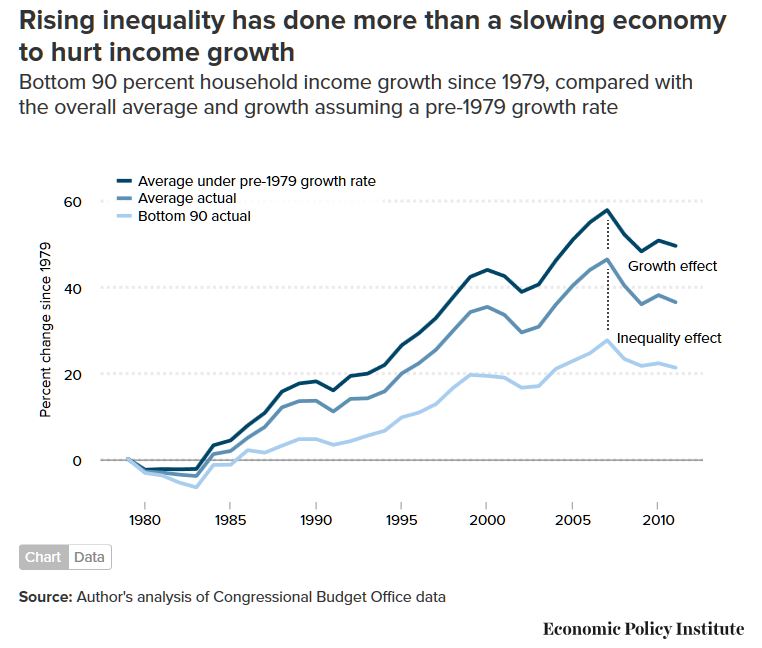

The rise of inequality over recent decades has been largely driven by a host of discrete policy changes that have regressively redistributed income to those at the very top. Many of these policy changes were championed by claims that they would boost overall growth rates, but Bivens argues that they have clearly failed on that front. The outcome of these policy changes have been a steadily rising “inequality tax” that has stunted income growth for the bottom 90 percent of households relative to what the economy had to the potential to deliver.

“A range of economic policy changes in recent decades were made that had the completely predictable effect of increasing inequality,” said Bivens. “These changes were justified by claims that there would be such a large growth payoff that everybody would be made better off. They clearly failed: we got the large increase in inequality and didn’t get any growth payoff, so it’s time to try a new approach.”

Bivens notes that because there is no obvious general relationship between rising inequality and overall growth rates apparent in the data, economic debates should shift to the potential effect of specific policy changes. He notes that many of the agenda items high on the list of progressive policy proposals would clearly boost growth and progressively redistribute income. Examples of these policies include re-establishing the aggressive pursuit of full employment as a policy target, and the re-regulation of the financial sector. Other examples include ramped-up public investments in both infrastructure as well as investments in early childcare and education and environmental efficiency.

Conversely, the economic agenda put forward by those set on prioritizing only growth would have only trivial effects at best on this growth, but would reliably redistribute income upwards. Examples of items on this agenda include a focus on cutting tax rates, denuding federal regulations, and signing more trade agreements.

Finally, Bivens argues that the zero-sum character of much recent income redistribution can be harnessed to work for the vast majority. Policy changes that boost the economic leverage and bargaining power of low and middle-wage workers can boost their incomes while not doing any harm to overall growth. Examples of these policy changes include raising minimum wages, restoring rights to bargain collectively, restoring overtime rights for salaried workers, adopting more generous unemployment insurance, and instituting new paid leave rights.

“We can confront the rise in inequality head-on with policy or we can continue to have an economy that underdelivers for the vast majority,” said Bivens. “There is no one silver bullet that will restore shared prosperity—it will take an entire policy agenda. Luckily, we know this agenda’s elements. There are a number of policies that will boost both growth and progressive redistribution, and many more that will help the vast majority without harming overall growth.”

What this report finds: Boosting income growth for the bottom 90 percent requires a policy agenda that explicitly aims to halt or reverse the rise in inequality in the United States in recent decades. The economic evidence shows no generalizable relationship between rising inequality and faster growth. This is important good news. It means that an agenda based on progressive redistribution can unambiguously raise living standards for the bottom 90 percent and even likely be better for overall growth than the agenda promoted by those who are opposed to strong efforts to check rising inequality and instead want to focus solely on spurring overall growth.

Why this matters: The lack of a general relationship between inequality and growth means that specifics matter in policy debates. And the specifics of the modern “growth only” agenda will fail. Policies such as cutting top tax rates, deregulating industries, and signing more trade agreements will both fail to appreciably boost growth rates and continue to send a disproportionate share of income gains to the top 10 and 1 percents. The “growth only” agenda has already been tried, and the results have been slower overall growth and sluggish income gains for the vast majority in recent decades.

How we can fix the problem: Income redistribution over the last few decades has been a zero-sum process, with gains at the top essentially coming straight out of the pockets of the bottom 90 percent of Americans. This zero-sum dynamic means that intelligent policies—including but going way beyond smarter and fairer taxing and spending—can convert these lost potential gains for the bottom and middle into actual income increases without harming overall economic growth. We should:

- Use the levers of macroeconomic policy (monetary, fiscal, and exchange-rate policy) to target genuine full employment.

- Make investments that markets are not making—in early childhood education, infrastructure, school construction, energy efficiency, and public health care.

- Strengthen antitrust regulations and look for other opportunities to introduce competition to private markets, such as public options for health insurance and retirement savings.

- Reregulate many activities of the financial sector to squeeze out the activities that don’t enhance productivity or create efficiency but simply enrich well-placed actors within finance. A financial transactions tax is the clearest example of a policy that can stop this income skimming.

- Enact climate-change mitigation measures—realizing that policies beyond simply increasing the market price of greenhouse gas emissions can play large and useful roles.

- Strengthen regulations and institutions that help shift bargaining leverage from capital-owners and corporate managers to low- and middle-income workers. Key examples include higher minimum wages and labor law reform that allows willing workers to join unions and bargain collectively.

Spread the word