Black History Month always inspires references to Frederick Douglass, but this year, the celebration got off to a strange start with some stilted praise from President Trump. Tuesday, the president said that the 19th-century writer and abolitionist "is an example of somebody who's done an amazing job and is being recognized more and more, I notice."

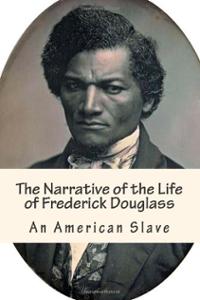

What, exactly, about Douglass caught the president’s eye was not clear, although the Twittersphere quickly lit up with satirical suggestions. But if you’d like to know more about this extraordinary American, the best place to start is with his first book, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.”Published in 1845, the autobiography came stamped with the declaration “Written by Himself.”

That claim of personal authorship was essential to Douglass’s freedom — and to his critique of America’s peculiar institution. Although it was illegal for slaves to learn to read or write, as a child in Baltimore, Douglass learned the alphabet from his owner’s wife, Sophia Auld. But when his owner discovered these lessons, he insisted they stop immediately. What’s more, he explained to his wife — while Douglass was listening — that such an education would “spoil” the boy and render him “forever unfit him to be a slave.” For Douglass, this was the first crack in the chains that enslaved him:

“These words sank deep into my heart,” he writes, “stirred up sentiments within that lay slumbering, and called into existence an entirely new train of thought. It was a new and special revelation, explaining dark and mysterious things, with which my youthful understanding had struggled, but struggled in vain. I now understood what had been to me a most perplexing difficulty — to wit, the white man’s power to enslave the black man. It was a grand achievement, and I prized it highly. From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom.”

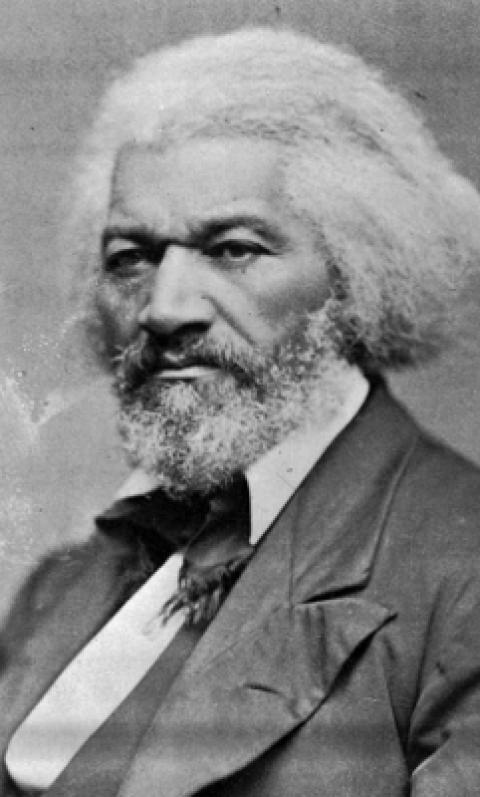

[Frederick Douglass: The most photographed American man of the 19th century]

Realizing the power of literacy eventually led to his escape and to the composition of this startling book. In his clear, vivid style and remarkably even-tempered tone, Douglass describes not only what he endured as a slave but also how slavery corrupted his white owners. Beyond its illuminating historical record, “Narrative” offers a poignant reflection on the psychological agony of emerging from slavery. Literacy and the self-knowledge that it enabled came at a high cost, as Douglass writes:

“That very discontentment which Master Hugh had predicted would follow my learning to read had already come, to torment and sting my soul to unutterable anguish. As I writhed under it, I would at times feel that learning to read had been a curse rather than a blessing. It had given me a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy. It opened my eyes to the horrible pit, but to no ladder upon which to get out. In moments of agony, I envied my fellow-slaves for their stupidity. I have often wished myself a beast. I preferred the condition of the meanest reptile to my own. Any thing, no matter what, to get rid of thinking! It was this everlasting thinking of my condition that tormented me … I often found myself regretting my own existence, and wishing myself dead.”

Fortunately, he resisted that despair, escaped to the North and blessed the nation with this revolutionary autobiography. It’s almost impossible now to fathom the full extent of his accomplishment. While Ralph Waldo Emerson and other white writers were fretting about what a new American literature might look like, Douglass was busy producing it. “Narrative” was an instant bestseller in America, England, France and Holland. Pro-slavery forces quickly charged that the book was a fraud because no slave could possibly write that well, but on his international lecture tour, Douglass demolished that lie. And 10 years later, he struck back against those accusations by producing a fuller and even more elegant version of his life story called “My Bondage and My Freedom.”

So, yes, he did an amazing job. The best job. Yuge.

[Ron Charles is the editor of The Washington Post's Book World. For a dozen years, he enjoyed teaching American literature and critical theory in the Midwest, but finally switched to journalism when he realized that if he graded one more paper, he'd go crazy. You can follow him on Twitter @RonCharles.]

Spread the word