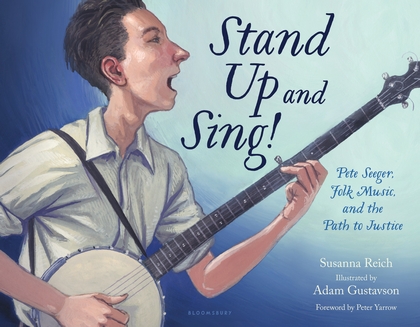

Susanna Reich, Stand Up and Sing! Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and the Path to Justice, illustrated by Adam Gustavson. (Bloomsbury, 2017, $18.95)

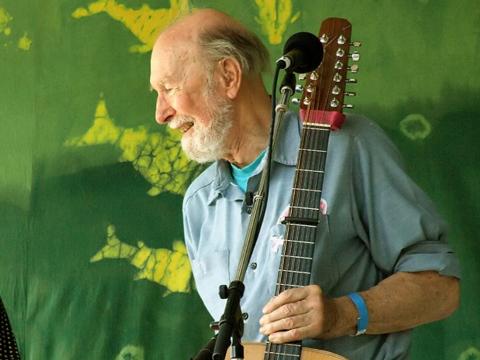

Every day, every minute, someone in the world is singing a Pete Seeger song. The songs he wrote, including the antiwar tunes, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” “If I Had a Hammer” and “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and those he popularized, including “This Land Is Your Land” and “We Shall Overcome,” have been recorded by hundreds of artists in many languages and have become global anthems for people fighting for freedom. For over six decades, he introduced Americans to songs from other cultures, like “Wimoweh” (“The Lion Sleeps Tonight”) from South Africa, “Tzena, Tzena” from Israel (which reached number two on the pop charts) and “Guantanamera” from Cuba, inspiring what is now called “world music.” His songs are sung by people in cities and villages around the world, promoting the basic idea that the hopes that unite us are greater than the fears that divide us.

Seeger helped catalyze the folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s. He inspired people to take up the banjo and guitar, encouraged young performers, helped start the Newport Folk Festival, and promoted the folk song magazine Sing Out! that he had had launched with other musicians and activists. Many prominent musicians—including Bob Dylan, Bono, Joan Baez, the Byrds, Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks, Bonnie Raitt, Holly Near, Tom Morello and Bruce Springsteen—consider Seeger a role model and trace their musical roots to his influence. Among performers around the globe, Seeger is a symbol of a principled artist deeply engaged in the world.

Seeger, who died in 2014 at 94, wouldn’t have cared that most of the people who sing his songs don’t know his name. But we should care, because Americans, especially young people, need to know about the people and movements who fought for things that today we take for granted. Learning how ordinary people overcame obstacles to bring about great changes helps give us the confidence and courage to overcome new obstacles and challenges.

There are three things we can do to make sure that Seeger’s spirit and legacy lives on.

The first, of course, is to follow his example of social activism. Seeger was a much-acclaimed and innovative guitarist and banjoist, a globe-trotting song collector, and the author of many songbooks and musical how-to manuals. But he was also on the front lines of every key progressive crusade during his lifetime—labor unions and migrant workers in the 1930s and 1940s, the banning of nuclear weapons and opposition to the Cold War in the 1950s, civil rights starting in the 1950s and the anti-Vietnam War movement in the 1960s, environmental responsibility and opposition to South African apartheid in the 1970s, and, always, human rights throughout the world.

The second thing we can do to sustain Seeger’s legacy is continue to listen to and sing his songs and to teach them to each new generation. Fortunately, Seeger recorded over 80 albums — including children’s songs, labor and protest songs, traditional American folk songs, international songs and Christmas songs — that have reached wide audiences. Seeger’s children’s songs, like the beloved “Abiyoyo,” are among his finest. Many of his performances and songs — including the TV show Rainbow Quest that he hosted on a public television station in New York in the 1960s — can be viewed and/or on the internet.

The third way to keep Seeger’s spirit alive is to teach our children about his life. Writer Susanna Reich and illustrator Adam Gustavson have produced a book dedicated to that objective. In 38 pages of text, paintings and drawings, Stand Up and Sing! Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and the Path to Justice provides a wonderful portrait of Seeger, focusing on how his strongly-held beliefs motivated his music and his activism. The book introduces children to the notion that music can be a powerful tool for change. As Reich notes, Seeger saw himself as a link in “a chain in which music and social responsibility are intertwined.”

There are several recent children’s books about Seeger, each targeted for different age groups, with different formats and writing styles, including Let Your Voice Be Heard: The Life and Times of Pete Seeger, Sing It!: A Biography of Pete Seeger and Listen: How Pete Seeger Got America Singing.

Stand Up and Sing is written for kids from ages six to 10. Six year-olds are most likely going to have the book read to them by a parent, teacher or caregiver, while many nine- or ten-year-olds will be able to read it themselves. The book conveys Seeger’s remarkable talent, convictions and courage without being preachy or talking down to children.

The book will also inspire adults, who may know Seeger’s songs but don’t know much about his life, to learn more about this remarkable figure. Reich includes a helpful bibliography of books, films and and interviews with Seeger that are available on the internet. Indeed, adults might want to search the internet to find videos of Seeger’s songs and performances to go along with reading the book to youngsters and to themselves.

By recounting Seeger’s life in words and pictures, the book allows the reader to move through the 20th century decade by decade, providing a history lesson in the process.

“Pete Seeger was born in 1919, with music in his bones,” the book begins, and from there Reich covers the key phases and moments in Seeger’s eventful life.

Coming of age during the Great Depression, Seeger saw poverty and adversity that would forever shape his worldview, but it wasn’t until he received his first banjo that he found his way to change the world. It was plucking banjo strings and singing folk songs that showed Seeger how music had the incredible power to bring people together.

His father (musicologist Charles Seeger) and stepmother (composer and folklorist Ruth Crawford Seeger) believed in the power of music to bring about change. His father took Pete to protest rallies about workers’ rights and other causes, which exposed him to the deprivation and hunger of ordinary people.

While he was in high school, Pete persuaded his parents to let him buy a banjo — a fateful decision that eventually changed American music and American history. During a visit to a folk music festival in North Carolina while still in high school, Pete saw rural poverty and heard bluegrass music played on a five-string banjo for the first time. When he returned home, he listened to records and learned to imitate what he heard – “rhythm, melody, chords, and words,” Reich notes. For the rest of his life, Pete learned, collected, played, and popularized songs by working people from around the country and around the world.

The book chronicles Pete’s exposure to radical ideas while at Harvard (from which he dropped out after his sophomore year to pursue folk singing) and after, his friendship with Woody Guthrie, his days playing with the left-wing Almanac Singers, his exposure to unions and his plan to help build a “singing union movement,” his experience in the South Pacific during World War 2, his marriage to Toshi, and their adventure building a log cabin home in Beacon, New York, overlooking the Hudson River.

Gustavson provides beautiful and haunting paintings and drawings of various aspects of Seeger’s life and of the times in which he lived. There’s Pete sitting on a piano bench while his father plays the piano and his mother plays the violin. We see a sketch of unemployed men lined up for free food during the Depression. The book includes illustrations of Seeger intently practicing his banjo, performing with Guthrie, shaving in his run-down apartment, and wielding an ax to construct his log cabin, with Toshi holding their baby near the tent where they lived while they were building the house.

Reich doesn’t ignore Seeger’s battles with Red Scare witch hunters that almost derailed his career. “Then,” the book reports, “a scary thing happened.” Reich recounts the infamous riot in 1949 at a Paul Robeson outdoor concert in Peekskill, New York, where right-wing thugs assaulted the performers and the audience members (most of them left-wingers) in opposition to their radical views.

“In 1955 Pete was called into court by some congressmen who didn’t think he was a loyal American,” Reich writes. “Pete refused to answer their questions in the way they wanted. The threat of prison would hang over his head for the next seven years.” This passage and others will surely raise questions about free speech and democracy that all Americans, young and old, should be asking, especially in the era of Donald Trump.

Reich describes how Pete and his folk-singing group, the Weavers, had major popular hits like “Goodnight, Irene,” then faced blacklisting by concert venues, television networks, radio disc jockeys, and mainstream record companies.

“During these years Pete could barely make a living,” Reich explains. A drawing of Pete playing his banjo in front of a group of young kids illustrates how he survived the blacklist, by performing at whatever colleges, schools, summer camps, churches and synagogues, and progressive groups would invite him.

“Meanwhile,” Reich writes, “the civil rights movement was picking up steam.” Readers learn that Pete popularized the song “We Shall Overcome” and taught it to Dr. Martin Luther King. Drawings of Pete singing with young activists, talking with King, and joining the march from Selma to Montgomery show us that he was helping spread the civil rights message through both his songs and his activism.

“Pete and Dr. King dreamed of peace,” the book explains, “but in the 1960s the United States was at war in faraway Vietnam.” Reich describes how Seeger came to write the antiwar song, “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy,” and how TV censors refused to allow him to sing it on the air, while Gustavson illustrates this episode with a sketch of soldiers wading through a river in Vietnam and another of him singing it in front of a TV camera. Reich doesn’t mention that it was the Smothers Brothers who invited Seeger on their show to perform it and CBS who edited the song out. She writes that “Luckily, a few months later he was invited back on TV, and this time seven million people saw him perform “’Big Muddy.’” She could have taught young readers a valuable Seeger-like lesson if she’d pointed out that he was invited back only because Americans flooded CBS with calls and letters in protest.

Reich tells the story of Seeger’s final, and successful, campaign, launched in 1969, to clean up the polluted Hudson River by mobilizing people to build the Clearwater, a majestic replica of the sloops that sailed the river in the 19th century. The effort, at first written off as simplistic and naive, helped inspire the environmental movement. The boat brought people to the river where they could experience its beauty and be moved to preserve it. The annual Clearwater festival, which Seeger started, continues to this day. The Clearwater conducts education programs for local school children to learn about environmental science and activism, a model of hands-on environmental education programs around the world. In 2004, the Clearwater was named to the National Register of Historic Places for its groundbreaking role in the environmental movement.

Reich writes: “A clean river, a peaceful plant, a living wage – as Pete got older, he continued to sing, to protest, and to inspire people to speak out for their beliefs.”

Although there are several illustrations of Seeger leading people in songs, unfortunately there’s no drawing of Seeger singing in front of large crowds, at a concert or political rally, with tens of thousands of people singing along. Seeger was a gifted and disciplined musician, with a remarkable repertoire of songs. Although he made it look effortless, he carefully crafted a performing style and stage persona that inspired audiences to join him. Every Seeger concert involved a lot of group singing.

Seeger’s remarkable spirit, energy and optimism kept him going through triumphs and tragedies, but he outlived all his enemies and remained one of the greatest American heroes of all time. He endured and overcame the controversies triggered by his activism.

In 1994, at age 75, he received the National Medal of Arts (the highest award given to artists and arts patrons by the U.S. government) as well as a Kennedy Center Honor. President Bill Clinton called him “an inconvenient artist, who dared to sing things as he saw them.” In 1996 Pete was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame because of his influence on so many rock performers. In 1997 he won the Grammy Award for his eighteen-track compilation album, “”Pete.” As Reich recounts in Stand Up And Sing, President Barack Obama invited him to lead 400,000 people in singing “This Land Is Your Land” at the Lincoln Memorial as part of his inauguration celebration in 2009.

Gustavson’s final drawing of Seeger standing on the edge of the Hudson River, wearing his knitted wool cap and flannel shirt, staring into the distance, with the Clearwater in the background, is a fitting symbol of his remarkable life as both a practical man and a visionary, a man who built his home and built a boat, but also built movements for social justice.

Inspired by the rhythms of American folk music, this moving account of Seeger’s life teaches kids of every generation that no cause is too small and no obstacle too large if, together, you stand up and sing!

_____________________________________

Peter Dreier is an American urban policy analyst, and Dr. E.P. Clapp Distinguished Professor of Politics, and director of the Urban and Environmental Policy Department, at Occidental College.

Spread the word