On a Wednesday morning in March, 19-year-old Devon Temple walked into his school’s computer lab and overheard two teachers talking about a classmate who’d been killed the day before.

“Tony?” Devon asked them.

“Tony Webb? With the fro?”

Devon and Tony grew up together in Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood. As kids, they’d drag a hoop into the street and play basketball on summer nights. They drifted apart as they got older, but they both attended an alternative high school called CCA Academy.

Tony chose CCA Academy after his social worker took him to a school fair at the Cook County juvenile courthouse. He’d missed a lot of school and wanted to get back on track. Tony’s mother had asked him many times if he wanted to take his classes online, but he preferred a more traditional high school experience.

On March 6, 2018, Tony put on a lilac collared shirt and black pants to fill out paperwork for his new job at a Portillo’s restaurant. Then he stopped to visit his girlfriend in Humboldt Park. Just before 8 p.m., as he walked to catch the bus home, Tony was shot once in his stomach. A half hour later, a doctor pronounced him dead.

The next day at school — on what would have been Tony’s 18th birthday — staff and students followed what has become a familiar routine for too many alternative high schools. A Chicago Public Schools crisis counselor sat among rocking chairs in the school’s peace room, ready to comfort anyone who came in. Devon and his civics teacher, Audrey Haywood, visited the counselor together. Seeing a teacher get emotional, “tore me up,” Devon said.

CCA students can count at least a dozen classmates and recent graduates who have died in the last several years, mostly by gunfire. After Tony was killed, Devon heard some students say: “People die every day. What of it?” For Devon, their response was as horrifying as the deaths themselves.

“It’s not normal to be that used to these things, even though, for us, it’s normal,” Devon said. “It’s not normal. It’s not.”

Higher death rates at alternative schools

A mural outside CCA Academy, an alternative school in the North Lawndale neighborhood on the West Side of Chicago, commemorates lost lives. Photo by April Alonso

While many CPS students have lost a classmate to gun violence, staff say it’s especially common in alternative high schools.

Some 425 Chicago public school students died between the 2013-14 and 2016-17 school years, according to a Chicago Reporter analysis of student transfer records. One in four attended an alternative high school, though these schools accounted for only around 2 percent of the district’s enrollment in that time period. Most of the alternative high schools where students died had a student body that was nearly all African-American.

CPS recorded 160 student deaths by gunfire in those years. It’s unclear if this is a comprehensive count, as district officials didn’t explain how they tracked shooting deaths. In response to a public records request, officials declined to say how many of these students attended alternative schools, saying doing so “has the potential to re-traumatize students and the community.”

These numbers don’t come close to capturing the damage wrought to families by gun violence, or the magnitude of loss felt by staff and students when a schoolmate is killed. They don’t include shooting deaths of recent graduates or dropouts. They don’t include students who were shot but survived.

There are a lot of reasons alternative schools have higher death rates. Many students were expelled or pushed out of traditional schools because of fights, arrests or gang involvement. They’re more likely than other Chicago high schoolers to live in or near neighborhoods with the highest homicide rates, a Reporter analysis of school and crime data shows. A two-decade-old national survey of alternative students — the only one of its kind — found a third had carried a weapon in the previous month and almost a fifth had attempted suicide within the previous year. Stresses students face today are likely worse.

Many alternative high schools are doing the best they can to help traumatized students with limited staff and funding. But until recently, district officials largely ignored alternative schools in this respect, even as they pumped millions into other schools to address students’ social and emotional needs. The turning point only came after student deaths spiked in alternative schools two years ago.

That lack of involvement stemmed in part from the fact that CPS outsources management of all but four of its 41 alternative schools to private operators, who face few consequences if they’re unable or unprepared to deal with student trauma. On top of that, privately run alternative schools tend to pay lower salaries and have higher staff turnover than traditional CPS schools — jeopardizing stability for students who need it the most.

Helping students cope with trauma

Rocking chairs are available in the peace room at CCA Academy, where students can go to seek grief counseling, calm down or talk about other issues at school. Photo by April Alonso

Research has long shown that traumatic events like exposure to gun violence can greatly affect student learning. It gets worse if it happens over and over again. Kids may find it hard to concentrate on their work, may withdraw from their peers or act aggressively. A researcher who looked at nine years of crime and school data found that CPS students living in neighborhoods with high rates of violence fell farther behind their peers in safer neighborhoods as they got older, especially in math.

When students are killed, the classmates they were closest to are most affected. But the death of a well-known student can disrupt an entire school for days, or weeks. That happened two years ago at Innovations, an alternative high school in the Loop, when a popular 17-year-old basketball player was shot and killed and students saw video of his body on Instagram. School administrators got counseling for the whole basketball team and brought vans of grieving students to the funeral.

At Devon’s school, the death of 17-year-old Elijah Jones in December 2016 hit classmates especially hard because he was shot about an hour after he left school. Elijah had recently shown up to school with a black eye, Devon recalled. “You want to lend a hand,” he said, “but you can’t reach that far.”

The grieving rarely stops after the funeral. Students say they’re often reminded of deceased classmates on their birthday, at graduation or on the anniversary of their death. As a result, alternative school staff have tried to find ways to help students process what they’re feeling, sometimes by incorporating it into their lessons at school.

At McKinley Lakeside Leadership Academy in Bronzeville, Principal Irma Plaxico bought a hand-held machine that students use to make photo buttons of friends or family who’ve been killed. Last school year, Peace and Education Coalition High School in Back of the Yards, one of the four alternative schools managed by CPS, created a 10-week “first responders” class to teach students about the impact of trauma. After one student told teacher Stormie McNeal about watching a friend die, she brought in the Red Cross to certify students in CPR. McNeal plans to bring in an expert this year who can show students how to stop a bleeding gunshot wound.

“I realized we have to give them more tools to deal with these things,” McNeal said. “A lot of my students have been shot. It’s really scary to think about, but that type of training is needed.”

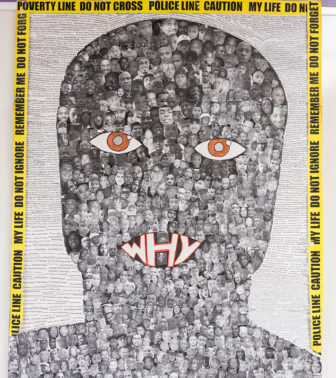

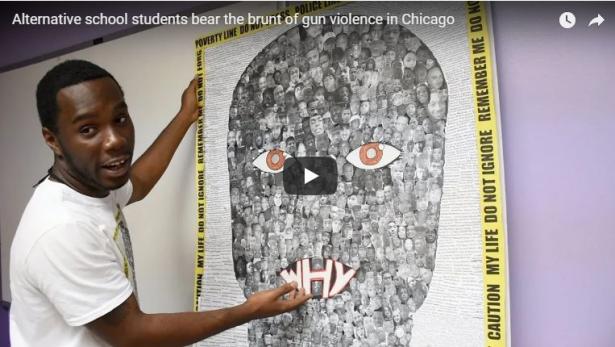

At CCA Academy, Devon and dozens of his classmates created a project in civics class that they called the “Face of Poverty.” Students scoured the internet for photos of every person who’d been shot and killed over the last two years in Chicago and used the images they found to make one giant face. Many students, their teacher said, knew five or six people on the poster.

Students at CCA Academy created “The Face of Poverty,” a collage of every person who’d been shot and killed in Chicago. Click to see video on the project. Photo by April Alonso

Students also researched systemic problems, like poverty and segregation, that contribute to Chicago’s gun violence. The project helped 19-year-old Chyann McQueen understand why so many of her young black male friends had been shot and killed, and reinforced her desire to work for change in her community.

“I grew up with those people and to see their lives cut short, it made me want to know why,” she said. “I found why, and now I want to combat that… I know that even though a lot of people see this as their reality, it doesn’t have to be their reality.”

As students in hundreds of schools across the country walked out of class in mid-March to protest mass school shootings like the one at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, Chyann organized a walkout at her school, too.

CCA students used the protest not just to draw attention to classmates who’d been shot and killed, but to the lack of investment in Chicago’s segregated black and Hispanic neighborhoods where shootings are most likely to occur. On the street outside school, Devon and Chyann’s classmate, 18-year-old Odessey Stewart, yelled through a megaphone for better-funded schools, more jobs and more mental health centers in her community.

CCA students held paper tombstones for several classmates who’d died by gunfire, including one each for Tony, Elijah, and 16-year-old Pierre Loury, who was shot and killed by Chicago police in April 2016 after he allegedly pointed a gun at an officer. The students also chose to honor 19-year-old Kenneka Jenkins, a recent CCA grad whose death, while not a homicide, drew national attention after her body was found in a Rosemont hotel freezer last year.

Tony’s mother, Perinda Lee, felt both inspired and overwhelmed by the students’ protest after her son was killed. “I couldn’t believe that he was on a poster, that he was actually gone,” she said. “It kind of took my breath away.” After the walkout, students hung the tombstones in the computer room at school. A classmate brought Tony’s to his house; now it hangs in the bedroom he used to share with his younger brother.

When students see acknowledgment of what’s happening around them, it can be a source of catharsis.

But alternative school educators and students say they often feel like their classmates’ deaths are overlooked by the rest of the city. Contrast that with Baltimore, where in a ceremony outside the district’s headquarters the schools chief read the names and schools of every public school student who was shot and killed last year. After each name, a bell rang. Three of the nine students had attended the same alternative high school.

Inadequate staffing

A brown paper tree adorns the entrance to Ombudsman South with notes written by students. Ombudsman, which runs three alternative schools, began hosting a mental health summit after two dozen of their students were shot, killed or involved in shootings in one year. Photo by Kalyn Belsha

CPS began beefing up staff and funding six years ago to help students cope with trauma. The district now employs a dozen or so specialists who train staff to address trauma and other social and emotional needs. But it wasn’t until last year that CPS targeted alternative schools. Before that, alternative schools themselves sought out trauma trainings from outside providers, which sometimes cost thousands of dollars. Now two CPS specialists work exclusively with alternative schools.

“We saw an opportunity to bring the work that we’ve been doing across the district to… a student population that has had a lot of needs in the last couple years,” said Justina Schlund, who directs the CPS office working to address trauma in schools. “Almost every single school, right off the bat, wanted more supports from our team.”

These specialists also help schools apply for what’s known as a “restorative practices coach.” The coach works to reduce disciplinary referrals and improve a school’s internal climate. Over the last three school years, CPS paid for these coaches in about 120 schools. Last year, for the first time, four alternative schools got a coach.

When Elbert Thomas coached at Ombudsman South, he helped the staff set aside time to talk about their stressful and often frustrating jobs, a technique that can reduce burnout. “It was just so needed for them to have that… opportunity to vent and be heard,” he said.

CPS officials admit it took them longer to provide these supports to alternative schools because many of them are run by private operators that the district hasn’t always worked with closely.

For years, the district relied on a single nonprofit, Youth Connection Charter School, to run most of its alternative schools. Many YCCS schools, like CCA Academy, have deep roots in their communities. But five years ago, district officials let several out-of-town operators, some of which are run by for-profit companies, open more alternative schools.

Since then, some critics have raised questions about the quality of these newer operators, who tend to spend less on school staff. Administrators of these alternative schools say it’s hard to keep their social worker positions filled — they often lose them to higher-paying jobs in other CPS schools.

Though social workers and school psychologists who work in alternative schools sometimes have smaller caseloads than clinicians who work in traditional schools — which are woefully under-staffed in this regard — many experts agree they still don’t have enough staff to meet their students’ mental health needs.

That’s been true for years at Peace and Education, where a social worker came just one day a week to meet with special education students. This school year, CPS is assigning a full-time social worker to the school, along with two other district-run alternative schools for young mothers and students incarcerated at Cook County Jail. The announcement came as such a shock to Peace and Education’s principal, Brigitte Swenson, that she had to re-read the email several times. “It’s a lot more than we’ve ever had,” she said.

Meanwhile, schools are doing a better job identifying issues rooted in trauma, which increases the number of students referred for more serious counseling.

On a recent Thursday morning, Ombudsman officials invited mental health providers and community groups to attend their second-annual “partnership summit.” Ombudsman, one of the district’s newer operators, started hosting the event after two dozen of their students were killed, shot or involved in a shooting in a year.

Dozens gathered at Ombudsman South, next to an abandoned fitness center in a Chicago Lawn strip mall. Inside the school’s entrance, a giant brown paper tree was filled with encouraging notes written by students. “I am more than my mental issues,” one student wrote. “I can take care/manage to control my PTSD and anxiety,” another message said.

One by one, each of Ombudsman’s three principals got up in front of the crowd, microphone in hand, and begged for help for their schools. One principal requested assistance with suicide prevention, student depression and anxiety. Another asked for mentors for Hispanic students in gangs. The third wanted help for students who get angry and shut down or abuse drugs and alcohol.

“We cannot do this without you,” said Lytina Lampley, the principal of Ombudsman West. “We need someone who’s going to come in and be committed to the work.”

“You have a chance right now”

Demetrius Archer's shoes and the uniform shirt of the school he attended before enrolling in Sullivan House are placed under hte memorial his mother Tammasha O'Neal created for him in her home. Photo by April Alonso

“I don’t know how I have the strength to talk to y’all right now.”

Two years ago, Tammasha O’Neal stood before dozens of students from Sullivan House, a YCCS alternative high school in South Shore that’s had more student deaths than any other CPS school in recent years. That includes 17-year-old Laquan McDonald, who was shot 16 times by a Chicago police officer, sparking citywide outrage.

“I don’t talk in front of people,” O’Neal continued. “But I have to now, because I’m dealing with this.” She motioned to the urn and death certificate of her 20-year-old son, Demetrius Archer, who’d been in and out of Sullivan House when he was killed in June 2016. He was shot sitting in a lawn chair around the corner from his mom’s apartment while hanging out with some friends.

When O’Neal heard that Sullivan House hosted an annual anti-violence ceremony, she volunteered to speak. She wanted to encourage her son’s classmates to get the diploma he never did.

“You have a chance right now,” she told them. “You’re at a school where… you mess up, they let you come back. Everybody don’t give you that opportunity.”

O’Neal wished her son had gotten more opportunities, like his older sister, who attended a selective-enrollment high school where she took advanced classes and went on college tours. If more students like her son got the mentoring, tutoring and other supports they needed, O’Neal said, fewer would end up in alternative schools.

“ need more counselors and therapists at the schools,” she said. “Somebody that these kids can go and talk to when they’re dealing with issues of just trying to make it to school every day.”

In many ways, O’Neal felt her son had been ignored, even in death. For months, her son’s blood stained the sidewalk where he was shot. When O’Neal realized no one from the city was going to clean it up, she bought grey spray paint at the local hardware store and covered it herself.

After speaking at Sullivan House, O’Neal added a photo of her son to a wall at the school of other students who’d been killed. There were so many photos, she said, she had to find space for Demetrius. It gave her some hope to think that maybe her son’s classmates would stand there and repeat to themselves: “I don’t want to be on this wall. I don’t want to be on this wall.”

Kalyn Belsha is a reporter for The Chicago Reporter. Email her at kbelsha@chicagoreporter.com and follow her on Twitter @kalynbelsha.

Cayla Clements is a reporting intern with The Chicago Reporter. Follow her on Twitter @caylaclements_.

Subscribe to The Chicago Reporter. Sign Up for Our Free Newsletter

Become an e-subscriber to The Chicago Reporter to receive our free newsletter and keep up-to-date with all of our major stories on race, poverty, and income inequality. The Chicago Reporter, published by the Community Renewal Society, is committed to protecting your privacy. We never share personal information without your consent. View our full privacy policy.

Spread the word