While Democrats and Republicans argue over the midterms, popular activists have carried new candidates to success

Depending on which media you consume, Donald Trump will either leave office in handcuffs – or coast to a second term. Making sense of American politics has never been easy, but the extreme polarisation of the press and the public has made it much more difficult.

Last month’s midterm results were no exception. Were they a vindication of President Trump and the Republican party, who strengthened their grip on the Senate, or a triumph for the Democrats, who regained control of the House of Representatives? While there is evidence on both sides of the argument, the question itself misses the point. So does the media focus on whether there really was a “blue wave” carrying Democrats to victory or a “red wall” based on Trump’s personal popularity protecting him and his party.

Elections are what Jane McAlevey, a union organiser I interviewed , calls “a structure test”: a clear means of determining the balance of power within a given institution, from a hospital or a factory to the White House and the halls of Congress. McAlevey and the unions she advises win good contracts for their members and wage tough strikes even in so-called right to work states such as Nevada. Her example is relevant because despite Democratic control of the House, the American political landscape remains hostile terrain for anyone who cares about racial justice, economic equity, climate change, women’s autonomy and the threat of nuclear Armageddon.

The real question is what is happening at the grassroots. What explains Trump’s enduring popularity, not just among hardcore racists, but among blue-collar workers who voted twice for Barack Obama? How did Andrew Gillum and Stacey Abrams wage such competitive races in the south? What powered Ilhan Omar to victory in Minnesota, Sharice Davids (who is Native American and lesbian) in Kansas, Colin Allred in Texas, Antonio Delgado and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in New York?

I’ve been travelling through the US since August 2015, when I reported on the first Republican presidential debate. (The one with so many contenders the organisers split proceedings into a main event and a preliminary bout, or “kids’ table” for also-rans such as Lindsey Graham and Wisconsin governor Scott Walker – who happily has now been replaced by Tony Evers, an unabashed progressive.) At the time I wrote that “no one on that stage is capable of stopping” Donald Trump, whose “unpredictability – his manifest inability to respect the norms of party, civility, or any institution or structure not bearing the Trump name, preferably in gilded letters – makes him the campaign equivalent of crack cocaine”.

That remains true today, and Democrats who underestimate Trump, or simply dismiss his supporters as “a basket of deplorables”, do so at their peril. Yet the midterms also showed that Trump can be beaten – even in red states such as Iowa, where Abby Finkenauer, the daughter of a union welder, became one of the youngest women ever elected to Congress., where she’ll be joined by fellow Iowan Cindy Axne, whose opponent, incumbent Republican David Young, was favoured by a Trump train stop in October, when the president told the crowd in Council Bluffs “a vote for David is a vote for me”.

The paradox of US politics is that whenever Americans are asked whether they support universal healthcare, guaranteed paid leave for carers, free education at public colleges, higher taxes on the rich, or any number of items from the Bernie Sanders campaign platform, a majority are always strongly in favour. The passage of ballot measures raising the minimum wage in Arkansas and Missouri, expanding Medicaid coverage in Nebraska and Idaho, and legalising medical marijuana in Utah suggests that even where voters don’t vote for Democratic candidates, they still favour progressive policies.

Even ideas long deemed too radical to be taken seriously by mainstream media – having the government produce inexpensive generic drugs or guarantee employment for anyone genuinely unable to find work, or treating the internet as a public utility, with publicly owned providers replacing private corporations – turn out to be favoured by a majority of Americans. Yet here we are with Trump in the White House, Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch on the supreme court, and Mitch McConnell in command of the Senate.

So how do we, as they say in New England, “get there from here?” Over the past two years I have interviewed dozens of activists in different parts of the US and profiled seven of them at length. These are people you have probably never heard of but whose efforts are laying the groundwork not just to take back the White House and the Senate in 2020 (when the electoral map will be far more favourable to Democrats) but also to take back the country, by assembling a new radical majority committed to fighting for the things Americans have long wanted but which a broken political system has kept off the agenda.

Labour is an essential part of any radical majority. The work McAlevey has done winning strikes and organising unions under the most difficult conditions is crucial, as is her distinction between mobilising – getting your supporters to the polls, or the picket line – and organising, which involves difficult conversations trying to win over people who don’t already agree with you.

Until recently most of the left, and all of the Democratic party, concentrated almost all of their resources on mobilising, or “turnout”. Beto O’Rourke’s surprisingly strong challenge in Texas, and a host of unheralded victories across Texas, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan are the fruits of a new effort by a generation of young organisers committed to building political power from the grassroots: organisers such as Waleed Shahid and Corbin Trent of Justice Democrats, a group calling for “a Democratic party that fights for its voters, not just its corporate donors”.

I met Shahid, the son of Pakistani migrants, when he opened the Sanders office in Philadelphia; I first crossed paths with Trent in Nashville, not far from the small east Tennessee town where he was born and raised. At the time the group had only managed to recruit a single candidate: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a former bartender from the Bronx who went on to defeat Joe Crowley, a 10-term Democratic incumbent, and is now the youngest woman elected to Congress.

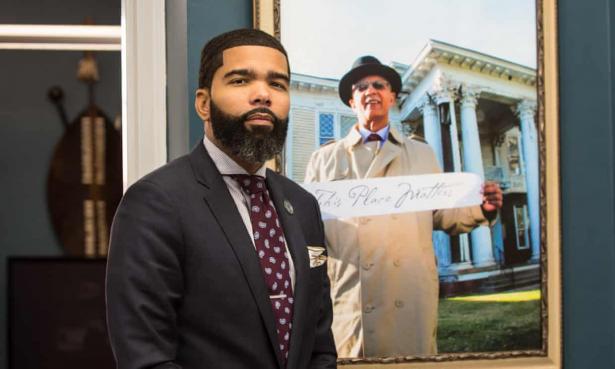

Or Jane Kleeb, the rural organiser who put together an unlikely coalition of ranch owners and Native Americans – the “Cowboy Indian Alliance” – to stop the Keystone XL pipeline, and is now head of the Nebraska Democratic party. Or Carlos Ramirez-Rosa, the former migrant rights activist who is Chicago’s youngest alderman, and whose work represents a new model for big-city politics. Or the mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, the son of black nationalists who wants to make Jackson “the most radical city in the country”. Or Zephyr Teachout, whose powerful critique of corporate corruption maps a way out of the US’s new gilded age.

When Benjamin Franklin walked out of the constitutional convention in 1787, he was stopped by a woman who asked whether the new country would be a monarchy or a republic. Franklin replied, “A republic, madam – if you can keep it.”

Can the US keep it? Elections alone won’t answer that question. But history shows that Americans have come together in the past, to defeat not just British rule, but the slave power of the Confederacy, and the “economic royalists” of the Great Depression. It has happened before. It can happen again.

[DD Guttenplan is the author of The Next Republic. He is London correspondent for The Nation and the author of American Radical: The Life and Times of IF Stone.]

Spread the word