One afternoon last summer, Xiongpao Lee was walking around a festival in St. Paul, Minn., armed with a stack of forms. Lee was there to find other residents who, like him, belong to the area’s large Hmong immigrant community. As he stopped and chatted with folks throughout the day, he had a very specific topic on his mind: the 2020 Census.

The Twin Cities is home to the nation’s largest Hmong community, South Asian immigrants with ancient ethnic roots in China. But a segment of that population remains hard to reach, in part because of a significant language barrier. That’s something Lee and members of the Hmong American Census Network want to overcome.

At the festival, he spoke with several people, explaining what the Census is and how it works. He cited dollar figures on how much funding is dependent on the count, and he discussed how Minnesota is on the verge of potentially losing a House seat. “Even the people who are aware of the Census,” Lee says, “don’t understand how the Census affects decisionmaking and policymaking.”

Then he handed over a form to sign, a pledge promising to participate in the Census count next year. Lee and his fellow network organizers are gathering similar pledges from various festivals, picnics and other events. Closer to the Census, they’ll start going door to door, and once the questionnaires are mailed out in the spring of 2020, the group plans to call everyone on its list to remind them to participate. “Culturally, having that one-to-one conversation is really building more of a relationship and trust with community members,” Lee says. “It carries more weight than just a text or email.”

The whole effort seems more like a political campaign, or a concerted get-out-the-vote drive. But it’s just one of the many ways that community groups, nonprofits and governments are working to ensure that people are counted in the 2020 Census. As with any decennial count, local leaders are keenly aware of its critical role in congressional apportionment and directing hundreds of billions of dollars in federal funding.

But with several looming uncertainties, the stakes are even higher this time around. Americans will be able to complete the Census online for the first time, making it more convenient for many households but leaving others without Internet access behind. Relying more on technology, the Census Bureau will devote fewer resources to field operations. The agency says it plans to hire between 350,000 and 375,000 enumerators, down from 516,000 in 2010. Then there’s the political environment, which has prompted fears in immigrant communities that many worry could result in an undercount.

By far the largest unknown remains the fate of a proposed question requesting an individual’s citizenship status. The Trump administration last year moved to add the question, but state and local officials, along with many government associations and advocacy groups, have strongly opposed it, saying it would taint the Census. The Supreme Court has agreed to take up the matter; observers expect the issue to be resolved by the time the Census Bureau begins printing operations in June.

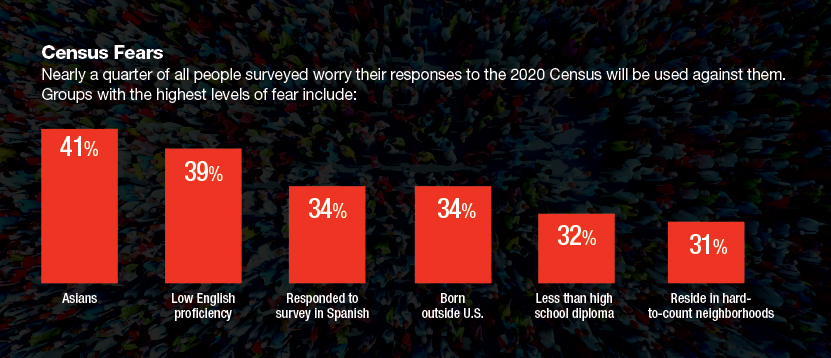

(SOURCE: 2020 Census Barriers, Attitudes and Motivators Study)

In the meantime, many communities are already getting ready. They’re organizing their Census efforts and holding initial meetings of what are known as Complete Count Committees. Several states have allocated targeted funding, although most haven’t yet committed substantial sums of money. Some of the most novel ideas for Census outreach initiatives often originate with nonprofits.

To get a sense of the ideas being considered around the country, Governing interviewed two dozen officials with state and local governments, nonprofits and the Census Bureau. Here’s a look at some of the more innovative ways they’re planning to ensure that all residents are counted.

Targeted Follow-Up

Minnesota is hardly the only place worried about an undercount of immigrant residents. In Miami, for example, with hundreds of thousands of immigrants from all over the world, counting area residents represents an especially daunting challenge. Many residents who moved from places such as Brazil and Haiti don’t speak English or Spanish, and they need assistance responding to the Census. Others, after fleeing their home countries, may be wary of the federal government collecting their information.

Lubby Navarro, a Miami-Dade County school board member who led the county’s 2010 organizing efforts, predicts that this Census will require a greater level of engagement. Compounding concerns about immigrants not participating, the Miami region has experienced substantial growth over the decade, and with it a housing shortage. Householders may be hesitant to identify all the people living there if they think it could get them in trouble with landlords. “I am very fearful of a large undercount,” Navarro says, “especially for minorities and hard-to-count populations.” A Census Bureau planning survey found about a third of foreign-born respondents expressed fears that their responses to the 2020 Census would be used against them.

In 2010, the Census Bureau published initial data showing rates of completed questionnaires several weeks after they were mailed. Miami-Dade County used it to identify a couple dozen low-responding neighborhoods, denoted as Census tracts, to target their follow-up efforts. County employees and volunteers from local organizations went door to door and held events in the neighborhoods urging residents to participate. An automated phone system called families in low-responding areas reminding them to fill out their forms. It was important, Navarro says, that they had the right people on the ground assigned to cover neighborhoods they either lived in or were familiar with. “You want people who know the buildings and are not fearful of going to the areas,” she says. “If not, you’re going to have a disconnect.”

In households with language barriers, kids often serve as translators for parents. So officials in different states say they’re seeking to incorporate the Census into the K-12 curriculum. Mailed questionnaires will be printed in English and Spanish, while the online form will be available in several other languages.

Miami-Dade County Commission Chairman Esteban Bovo Jr. intends to carry out a focused follow-up effort in 2020. He emphasized the need to reassure residents their information is safe and show how programs they depend on rely on an accurate count. “It’s not just a challenge of logistics. It’ll be a political challenge, too.”

The ‘Shadow Census’

Detroit might not wait until 2020 for its Census. City officials are in the planning stages of what Victoria Kovari, who heads the Department of Neighborhoods, calls a “shadow census.” The idea is to conduct a scaled-down dry run in the city’s seven council districts later this year to gather crucial information for the actual count.

Kovari said the effort could consist of a massive number of volunteers going door to door, the city sending out its own forms or a combination of both. “We want to be able to identify key leaders in each of these Census tracts, strengthen and build the network that will pay dividends down the road,” she says. Like other cities, Detroit maintains databases of addresses that it shares with the Census Bureau for mailing out questionnaires. Part of its testing will include sending out print newsletters and fine-tuning the mailing address data based on bounce rates.

A Census dry run could be particularly useful in a city like Detroit, which has experienced major population shifts over the past decade. As parts of many neighborhoods have been demolished and residents have moved to different parts of the city, officials hope to gain a better understanding of where housing units are vacant or occupied. That way, they’ll know where to best target their efforts come 2020.

Resource Sharing

Back in 2010, the city of Los Angeles and surrounding L.A. County each pursued separate Census outreach efforts. This time around, they’re working together, forming a joint Complete Count Committee and collaborating on a slew of different projects. “We eliminated the duplication of efforts and the need for our partners to go to two different meetings where we’re talking about the same thing,” says Maria de la Luz Garcia, director of the city’s Census initiative. The two governments are, for instance, planning joint efforts for Census recruitment and establishing universal definitions of hard-to-count populations so that everyone is on the same page.

Meanwhile at the state level, Ditas Katague, California’s Complete Count director, is developing a mapping tool to help guide planning statewide. It’s expected to include hard-to-count populations, Internet subscription rates and areas where partner organizations are working, among other data. Officials anticipate also using the tool to redeploy resources in real time: The Census Bureau has agreed to share a daily feed of response rates with California in 2020.

The California Legislature has allocated $90 million for Census outreach, dwarfing funding other states have earmarked so far and far exceeding the few million dollars California budgeted for 2010. The idea is to bolster grassroots organizing, with nearly all the funding distributed to counties and their partners. “What we see sitting here in Sacramento,” Katague says, “may not be as effective as the messaging that comes from the local level.”

To augment its state funding, the city of Los Angeles has entered into a public-private partnership with the California Community Foundation for a local pooled fund. The city has already committed $2 million, significantly more than in 2010. But the additional investment, while significant, still pales in comparison to just how much it could lose from an inaccurate count. The city estimates it receives between $700 million and a few billion dollars in annual federal funding on the basis of its immigrant population alone. “The city is heavily invested, and part of that is the environment we’re in,” de la Luz Garcia says.

Other places across the country are exploring similar public-private partnerships. King County, Wash., for example, is looking into a pooled regional funding model with its localities and philanthropic organizations. County official Dylan Ordoñez says the aim is to “remove barriers and make dollars easier to access through consolidation.”

Kiosks

For the first time, Americans will have the option of completing the Census online in 2020 instead of filling out a paper questionnaire. But many poorer households, already among the most difficult to count, lack Internet access.

To bridge the digital divide, a number of local governments plan to set up kiosks at different locations where residents can complete and submit their responses online. “It’s really trying to make the Census as accessible and as forward-facing as possible so people know it’s there, and hopefully avoid an undercount,” says Nick Kuwada, who is heading Census coordination for Santa Clara County, Calif.

What these kiosks actually look like has yet to be determined. For its test in Providence County, R.I., last year, the Census Bureau installed special terminals in post offices. Local governments might opt instead to set up laptops at tables or use iPads or other computer tablets. “It’s going to be flexible and fluid because it will be in a lot of different places,” Kuwada says. “If it’s in a place of worship, it might look a lot different than if it’s in a county hospital.”

The Census Bureau installed kiosks in 30 Rhode Island post offices last year to test the technology. In 2020, Americans will be able to complete the Census online for the first time. (U.S. Census Bureau)

Libraries have always played a major part in promoting enumeration efforts, hosting more than 6,000 Census outreach sites for the 2010 Census, according to the American Library Association. But their role could be even larger this time, given that the federal government is shifting to online enumeration, opening about half as many area Census offices as in 2010. Library staff could offer assistance at kiosks, or patrons will follow prompts after they log in to computer systems directing them to complete the online form.

Recreation centers or schools could also house kiosks; Wi-Fi kiosks could even be located in public spaces outdoors. Los Angeles has proposed mobile kiosks for airport passengers waiting at Los Angeles International Airport. To reach hard-to-count populations, officials are especially interested in placing kiosks in establishments with a high degree of public trust, such as health clinics or houses of worship.

Staffing Up

In every community, staffing is crucial for obtaining an accurate count. Temporary staff, including enumerators who follow up with nonresponding households, are a major part of any Census effort. But the federal government has struggled to hire enough qualified enumerators in prior Censuses, and recruitment in 2020 could be especially challenging if the economy remains strong and few people are looking for work. A recent report from the Government Accountability Office found small applicant pools and high turnover have hindered early hiring thus far.

That’s part of the reason why the National League of Cities (NLC) is recommending officials become more engaged in recruitment than they have in the past. “It’s an opportunity for city leaders to go into the communities they know will be hard to count, tap into social service organizations and connect them to these jobs,” says Alex Jones, the manager of NLC’s Local Democracy Initiative.

One city that’s focusing extensively on recruitment is San Jose, Calif. “We feel like the enumerators are going to play a huge role in bringing up response rates,” says San Jose Director of Strategic Partnerships Jeff Ruster. It’s critical, Census coordinators say, that these employees are trusted in their assigned communities and can overcome any language barriers. Another challenge is that it can be hard to keep temporary Census hires on board for the duration of the job: Many of them quit early if they find other employment. San Jose plans to limit attrition by connecting hires with full-time positions once the Census wraps up. The city has worked with local employers to identify jobs with similar skill sets, positions such as customer service representatives, insurance claims clerks and eligibility interviewers for government programs. With the prospect of full employment on the horizon, the city hopes enumerators will be more likely to serve their full terms.

New York City plans to augment the Census Bureau by incorporating Census work into its summer youth employment program. While participants will not be canvasing alongside enumerators—federal law prohibits volunteers from presenting themselves as federal employees—they will be able to assist in organizing and conducting outreach in targeted neighborhoods. New York is also exploring hiring noncitizens to help with outreach; they are often in the best position to connect with hard-to-count groups.

All Hands on Deck

Given the anticipated staffing constraints for the 2020 Census, many states and localities are planning to rely extensively on their own workforces to engage the public. While they’ve played roles in prior counts, the breadth and scope of mobilization efforts is widening for next year.

With its vast immigrant population, New York City says it plans to involve its social services agencies, police, parks and recreation workers, and several other public-facing departments. “New York is always in danger of an undercount,” says Deputy Mayor Phil Thompson. A unit in the mayor’s office will recruit city staff from all departments for outreach, language assistance and other activities. Some localities are considering offering Census assistance via their 211 phone systems, as many of the callers to those lines often correspond with historically undercounted groups.

California previously contracted with counselors in the Women, Infant, and Children (WIC) program to discuss the Census with their clients, who are among the most frequently undercounted. Other types of state-level departments with caseworkers might employ similar approaches.

New York views the Census as an opportunity to establish a dialogue with residents and maintain those lines of communication even after the count is over. Thompson recalls a meeting with residents of a Harlem public housing development last year. They agreed to assist with the 2020 Census, but also said they wanted help combating rats and raccoons. The city responded by establishing a public housing resident pest removal training program. “It’s not just about filling out a piece of paper,” Thompson says. “We want to create an infrastructure so that when people want to know where to go, we can use these very same networks.”

Spread the word