On May 9, 1978, Italians woke to sorrowful news reports about the murder of former Christian Democratic prime minister Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades. The same morning, in the small Sicilian town of Cinisi, the police found the body of Giuseppe “Peppino” Impastato, a young anti-mafia activist murdered by Cosa Nostra – the Sicilian mafia.

Impastato is commemorated each year as an example of young Italians’ fight against what was once the country’s most powerful criminal organization (and remains so in Sicily itself). Official memorialization presents this as a nonpartisan history that crosses political divides; this, even though Impastato’s own gravestone remembers a “revolutionary and communist militant killed by the Christian-Democratic mafia.”

This burial of the political character of the figures who have fought the mafia through the years has become a mainstay of public memory. It suits those who want to relegate this fight to a merely judicial matter – upholding legality – and ignore the social question behind it. Yet if for more than a century the mafia has waged war on rebellious peasants and farm laborers, communist and socialist militants, trade unionists and Communist members of parliament, the resistance against its control is equally political.

Since the last decade of the nineteenth century, the struggle against the mafia has been a struggle against the power of both the ruling classes and their allies; indeed, the mafia itself has over time merged the two categories. This is a Sicilian history but also a mirror of Italian national history and the massacres ordered by the state. Those who directed these crimes remain unpunished. Yet they belong precisely to that bourgeois power bloc that has for so long used armed groups, fascists, and the mafia to execute its orders.

Early Battles

Several studies have demonstrated that the mafia emerged in the last decades of the nineteenth century as an organization designed to protect the profits that the spike in the citrus fruits trade (and its foreign exports) had brought the latifondisti (big landowners). Mafia gangs defended profits not only on lemons and oranges but also on sulfur, as the mine owners sought organized protection. The gabellotti – entrepreneurs who rented and managed the big landlords’ properties – were also mafiosi or mafia-linked. They were flanked by the campieri, a private police force that kept order in the estates, as a sort of ancestor of today’s caporali (work-gang bosses) — figures who controlled the workforce by means of violent repression.

This in turn brought resistance. Such was the case of the Fasci dei Lavoratori (Workers’ Leagues), also known as the Fasci Siciliani (Sicilian Leagues), a popular movement that developed between 1891 and 1894 before it was bloodily repressed by the Royal Army under prime minister Francesco Crispi as well as the mafia. These Fasci emerged as a response by subordinate classes as Sicily’s landowners offloaded the costs of the island’s agricultural crisis onto day laborers and miners. Officially founded by Giuseppe de Felice Giuffrida on May 1, 1891, these Fasci were organized in territorial sections at the provincial level. They had an explicitly socialist approach, unlike the various other leagues that emerged in other Italian regions, which were strongly influenced by anarchism.

The movement of farm laborers, sulfur mine workers, and peasants demanded better working conditions, a shortened working day, increased wages, and a reduction of the duties owed to the landowners or the gabellotti running the farms. But they also called for agrarian reform that would redistribute land ownership. They were, by definition, against the mafia, because they were fighting both for status and in opposition to the economic and military oppression imposed by the mafiosi.

Epitomizing this stance, the Statutes of the Fascio of Santo Stefano Quisquina forbade members “to be associates a) with all those who have betrayed the Fascio’s goals . . . or who are known as vagabonds, mafiosi and men involved in criminal dealings.” These Fasci made one of the first great movements in Italy: as Antonio Labriola, one of the first and greatest students of Marxism in Italy put it, ‘This was the second great movement of the proletarian mass that we saw in Italy after the Roman one of 1888-1891.” Writing in 1893, a year before the government broke up the Fasci by force, Labriola here expressed a powerful “optimism of the will,” further adding that “The Sicilian movement shall never disappear.”

Alas, the movement was indeed broken up. But it did not die completely — for the fight for land and the liberation of the toiling classes, as well as the movement’s socialist inspiration (later complemented by a communist one) was destined to have a long history in Sicily, if an oft-forgotten one. Indeed, it was thanks to the “long wave” of the movement for land and a democratic agrarian reform that the Italian Communist Party (PCI) was able to build support on the island and become a mass party at the end of the Second World War.

In the April 20, 1947 regional elections the Communist and Socialist-run People’s Bloc secured 29.13 percent of the vote, as against 20.52 percent for the Christian Democrats. The popular layers of society organized, struggled, and voted against the power bloc of which the mafia was part.

An Anti-Left Bloodbath

However, in this cause they faced deadly repression. Already in the first months of 1947, before the election, the mafia had murdered Nunzio Sansone (founder and secretary of the camera del lavoro [labor hall] in Villabate), as well as Leonardo Savia — like Sansone, a Communist in the forefront of the fight for land reform. Mafiosi also killed the activists Accursio Miraglia and Pietro Macchiarella.

After the Sicilians gave their verdict at the ballot box, showing that they would not be intimidated, the mafia responded with an outright massacre at Portella della Ginestra on May Day 1947. At the rally to mark International Workers’ Day in the small Sicilian comune, a hail of machine gun fire killed eleven people and left almost a hundred injured.

This was a decisive moment in Italian history, for it put on display the forces behind the governmental bloc that took form in the postwar years. The Christian Democrats now ruled Italy together with conservative parties, in tandem with an alliance between the Northern industrial bourgeoisie and the Southern landowners — a pact of which the mafia was now very much a part, having built up its capital over earlier decades.

In this environment, the Communists and Socialists in opposition were enemy number one. And the interior minister in 1947 was one Mario Scelba, the anticommunist par excellence, who bloodily repressed the workers’ movement both in the immediate postwar years and then in the 1960s.

The anticommunist outlook of the Italian and Sicilian authorities resonated in the words of the ruling bloc’s other great ally: the Catholic Church. As we learn from Umberto Santino’s history of the fight against the mafia, in the wake of the massacre in Portella della Ginestra and another that followed in June, the then-cardinal of Palermo, Ernesto Ruffini, told Pope Pius XII what was happening in the following terms:

It is a fact that the reaction to left-wing extremism is taking on impressive proportions. Indeed, we could have predicted as inevitable this resistance and rebellion against the arrogant pretenses, the calumnies, the disloyal thinking and the anti-Italian and anti-Christian theories of the Communists. We are still overly afraid of these deluded masses manipulated by godless men.

It was also Ruffini who lobbied Alcide de Gasperi’s Christian Democratic government to ban the Communists, having already secured their excommunication by the Church itself.

The repression continued in subsequent years, reaping fresh victims among the ranks of Socialist and Communist trade unionists from Placido Rizzotto and Salvatore Carnevale. This repression was also bound up with the fate of the peasants’ movement as well as the unresolved Southern question — the class struggle outside of the factories. In these years the Left had to understand this relation between the proletariat and class struggle, between organization and class alliances, so as to provide a way forward of its own.

A Political Movement

Perhaps this was best expressed in the texts by Raniero Panzieri collected in L’alternativa socialista: scritti scelti 1944-1956. At the time a leader of the Italian Socialist Party, Panzieri was later a founder of operaismo (workerism). Sent by his party to Sicily in 1949, he was critical of the Left’s failure to understand the situation there:

Many comrades . . . think that the peasant movement and in particular land occupations are a “spontaneous” movement, in other words a purely economic one. I think that we need to be clear: politically, the peasant movement is an attempt at a democratic revolution. But on this level, it is far from a spontaneous and economic movement. It advances political and ideological forms and objectives no less than economic ones, for instance through [the demand for new forms of] local government, different administrative and tax justice, raising the cultural level, etc.

Indeed, the movement’s social demands were the opposite of the established Christian Democratic and mafioso-type power structures based on blackmail, speculation, and privilege. Seeking to protect this power, reactionary forces worked to prevent the Communists and Socialists from taking charge of local municipalities and city governments. They were repeatedly blocked from presenting electoral lists, through the intimidation and murder of those who stubbornly worked to make Sicily and its various localities into a land of democracy.

There were exceptional breakthroughs, as we see in the account of Vera Pegna, a young woman who moved to Sicily and joined the PCI in Palermo. While it might have seemed that the urgent demands of everyday action were the only real necessity, she studied the Communist Manifesto and Lenin’s What Is to Be Done — it was necessary for any militant who joined the party ranks to develop a solid theoretical grounding.

The center of her activity was Caccamo, one of the towns in which the mafia had stopped the Communists from taking part in the local elections. She challenged the power of the mafia boss Panzesca, and when the Communists then did stand in the 1962 vote, they won four seats. But this was a relative and rare success. Soon afterward Pegna left the island, shaken by the mafia threats and the sense of isolation.

Indeed, the mafia had never halted their fire against trade unionists of Communist and Socialist background. If in the 1955 regional elections the parties that comprised the People’s Bloc stood on separate lists for the first time since before Fascism, during the campaign they maintained a common front against the mafia. After all, earlier that year the mafia had killed several militants including Salvatore Carnevale, a laborer in the sulfur caves who was also secretary of the CGIL trade union’s section for builders. The Christian Democratic authorities (including the mayor) failed to show up for his funeral but the mineworkers and farm laborers turned out en masse.

Panzieri, who had in the meantime become the Socialist Party’s regional secretary, called a mass demonstration to commemorate these workers’ murdered comrade. Leading political figures from the regional and national levels turned out in the village of Sciara: from the then–regional CGIL secretary Pio La Torre to the Palermo PCI secretary Pompeo Colajanni and the Socialist MP Sandro Pertini (later president of the republic), who concluded the rally with an appeal to the class and especially the youth: “From his death we must take an example and an inspiration. And the example he left is one of loyalty to the working class and to the party.”

And it was again Panzieri who emphasized the intimate connection between all the class struggles against the bourgeois-mafioso bloc:

Salvatore Carnevale was born to bear witness, through his struggle and his life, to the irresistible reawakening of the peasant forces determined to assert their presence, their historical rights, their rights as humans in this country, in this land, against the squalid and inhuman forces of landowners, the barons, the mafiosi, and crime.

The Fall of the Movement

It was not the mafia itself that stopped the movement, but emigration: according to the National Statistics Institute (Istat), between 1946 and 1956 some 274,000 people left Sicily for Northern Italy or abroad (out of a population not much above 4 million), followed by another 352,000 in the following decade.

Most became workers and precarious laborers in the industries of the North, where their struggle would continue in all the sites of exploitation both within and outside the factory. This created a rift in those orthodoxies that tended to see the factory worker as the revolutionary subject rather than the working class as a whole. Yet this experience can also enrich contemporary debates on class struggle and migration.

In those decades Italy was going through the economic boom that followed postwar reconstruction, with accelerated industrial development in the South and not just the North. However, in the South this was limited to a few cases of heavily capital-intensive development, as well as a major growth in outsourcing of public projects by the state, from the reclamation of land for agriculture to the expansion of the region’s infrastructure. This brought considerable profits for both landowners and the urban bourgeoisie of which the mafia was itself part. The North’s industrial bourgeoisie put up no resistance to such developments.

A public body designed to put billions into financing the development of the South, the “Cassa per il Mezzogiorno” allowed the mafia to rack up profits and capital, becoming an economic power that would soon also shift to the Northern regions with even greater opportunities for profit. What followed were decades of bloodshed and mafia clan wars in which no one was spared – culminating with the killing of the carabinieri [military police] general Carlo Alberto dalla Chiesa in 1982 and the judges Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino in 1992. Despite its own internal strife, the mafia also hit out at the opposition coming from Communists and the legal system.

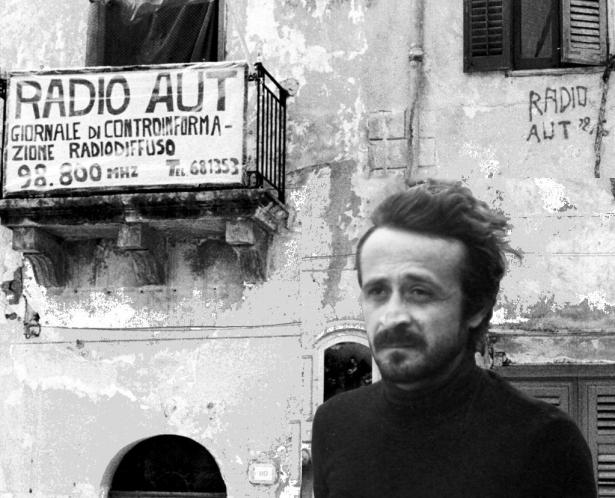

Exemplary of this was Peppino Impastato, the militant murdered in 1978, who was himself son of an affiliate of the Badalamenti clan. A young communist active in the extra-parliamentary left of the 1960s and 1970s, he supported the struggles waged by workers, farm laborers, and the unemployed. But above all, he was a defiant voice of protest against the expropriation of peasants’ land to build the third runway of Palermo airport. This was the key power base of enemy number one, the Cinisi mafia boss Gaetano Badalamenti, whose control of the airport guaranteed a sizable flow of drugs. Peppino irreverently reported on these goings-on at street protests as well as over the airwaves through the radio station he founded, Radio Aut.

On Badalamenti’s orders, Peppino was killed in an explosion. To hide the mafia’s hand in the murder the investigators and the press claimed that Peppino had accidentally killed himself while he was organizing a terrorist attack. In those years it was an established practice to blame bombs and massacres on the political enemy within, the communists. But the murder had been ordered by the local powers that be. Only in the 1990s was the Impastato case finally opened up again, with the accusations brought against Badalamenti and his right-hand-man Palazzotto, imprisoned for the murder in 2002.

In 1982, a few months before the killing of police chief Dalla Chiesa, another key figure in the anti-mafia struggle was also murdered by mafiosi: the Communist member of parliament Pio La Torre, who had been head of the Sicilian region of the CGIL union in the 1950s and a tireless militant in the fight over land. La Torre had insightfully detected the fault lines in the mafia as an organized system of power and capital accumulation.

It was because of his proposal — which later became law — that the mafia was recognized as a criminal organization, a system, and thus was punished not only through the imprisonment of its members but the confiscation of the assets under its control, from real estate to businesses and farmland. For the Communist, to strike at the heart of this business – part of capitalism – demanded an assault on its power to accumulate and its control and ownership of capital.

More than three decades have passed since that law was introduced, and the mafia is not dead yet. It has proven capable of transforming and working its way into the inner labyrinth of Italian capitalism, on the basis of the vast economic power it has been able to accumulate. Cosa Nostra is no longer using its weapons nearly as much as before. But it remains in control, in the absence of the organization and belief in progress that once drove so many communists to cut away at the roots of mafia power.

Marta Fana is the author of Non è lavoro, è sfruttamento(This Isn't Work, It's Exploitation.)

If you like this article, please subscribe or donate to Jacobin.

Spread the word