Madison, Wisconsin. A blustery Friday evening. A few thousand supporters of Vermont senator and presidential candidate Bernie Sanders are gathered in James Madison Park, along the shores of Lake Mendota. Though it’s April, it’s cold as hell. A group of Bern fans look ready to blow away in the breeze as their giant American and Wisconsin state flags fill up like spinnaker sails. When Sanders finally ascends to the lectern, all you can see from a distance is a shock of white hair whipping in the wind atop a shiny black overcoat. He looks like a gull in a Glad bag.

“When I was leaving Washington this morning, I was wondering — should I take my coat or not?” he says. “Right decision. Good!”

It’s the beginning of Sanders’ so-called Blue Wall tour, through five key Rust Belt states that fell to Donald Trump in 2016. Wisconsin is the first stop, to be followed by Indiana, Ohio, Michigan and Pennsylvania. Sanders is here to roll out his campaign’s core argument, that among Democrats he alone is positioned to retake voters lost by the party to Trump.

Within just a few minutes, Sanders gets to his money line:

“Of all the lies that told,” he says, “the biggest lie was when he said during the campaign he was going to defend the interests of the working class of our country.”

Sanders’ pitch to 60 million red-state voters is, Trump lied to you. He believes many of Trump’s supporters are denizens of a pissed-off working class who bought Trump’s promises of better jobs, benefits and security after decades of betrayal from both parties.

Sanders thinks the whole working class shares this anger, but this trip is overtly about the white portion of that demographic. That he’s even making a pitch to Trump voters is an act of defiance. Much of the commercial news media since 2016 has doubled down on Hillary Clinton’s “basket of deplorables” line, dismissing Trump voters as motivated entirely by racism. To court them at all, the thinking goes, is itself a form of white identity politics.

Sanders clearly disagrees. His speech is designed to remind everyone, Democrats as much as ostensible Trump voters, how explicit Trump’s promises on the “economic insecurity” front were and how miserably he’s failed at keeping them. Bernie has never said this out loud, but some of his frustration may come from the fact that candidate Trump in 2015-16 often borrowed from Sanders-esque critiques about corporate power; he even regularly made it a point to praise Sanders in speeches.

“Trump told the American people that he would provide health care to everybody, remember that?” Sanders says.

The crowd cheers a little. Perhaps not everyone remembers, but Trump did once promise “insurance for everybody,” adding a classic strongman’s pledge that “everybody is going to be taken care of much better than they’re taken care of now.”

Sanders lists other Trump pledges seemingly stolen directly from his own campaign. “I remember the ad that he ran, it was really a very good ad,” Sanders quips. “He said, ‘I, Donald Trump, going to stand up to Wall Street.’ Remember that? Oh, yeah, and we’re going to reinstate the Glass-Steagall Act.”

Sanders of course has long promised to reinstate the Glass-Steagall Act, a Roosevelt-era law separating insurance, commercial banking and investment banking. Sanders was mad in a copyright-infringement sort of way even then, and still seems it. (After Trump was elected, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin told Sanders that Trump’s promise of a “21st-century Glass-Steagall Act” did not actually mean breaking up banks, which would “ruin liquidity.”)

Sanders goes on to list other Trump whoppers: that “the rich will not be gaining” under his tax plan (in fact, 83 percent of the tax relief went to the top bracket), that he would bring manufacturing jobs back, and so on.

It all makes sense. The disconnect is the crowd isn’t exactly full of duped Trump supporters. Most of the assembled are young, progressive-leaning students whom Sanders had already won over in the last election cycle.

“I loved his 2016 campaign,” says Zach Farmer, a University of Wisconsin student, who adds he liked that Sanders “introduced things like Medicare for All, free college tuition, things like that.” Farmer was merely a fan in 2016 but plans to volunteer this time around, a typical representation of how the Sanders phenomenon has grown since the last election.

Despite his movement’s continuous growth, Sanders appeared to have a difficult winter. Former staffers accused him of ignoring “the issue of sexual violence and harassment” in the 2016 campaign. Tied to that were criticisms that his staff was overrepresented by white men, an issue that may have led to his longtime Svengali, Jeff Weaver, deciding not to run his campaign this time. This seemed to rattle Sanders, who has been tied at the hip to Weaver since dinosaurs roamed the Earth (read: since 1986, when Weaver was Sanders’ driver during the Vermont gubernatorial campaign).

It wasn’t just a theatrical delay when Sanders took a long time to decide to run; he was genuinely torn. Former staffers launched a Draft Bernie/signature-gathering campaign designed to prove he’d have the support he’d need to succeed. Sanders still took six or seven weeks after that to think it over.

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., greets supporters after speaking at James Madison Park in Madison, Wis., Friday, April 12, 2019. Photo credit: Amber Arnold/Wisconsin State Journal/AP

In 2016, Sanders ran a freewheeling campaign, occupying a Jeremiah-like role, roaming the planet speaking truth to power. Now, Sanders is a genuine contender, even if he’s seldom described that way. With almost no corporate support, he led all Democrats in fundraising in the first quarter. In the first week after a late-February launch, he pulled in an astonishing $10 million, coming from 359,914 donors, 39 percent of which came from addresses that had never donated to him before. By the end of March, he’d raised $18 million, with an average contribution of just $20, down from $27 in 2016. By mid-April he had a million volunteers.

But Sanders no longer has the breeze of low expectations at his back. What was merely a lack of institutional support in 2016 has transformed into active institutional opposition. Among the donor class, his own party’s leadership and in most of the commercial media, he is roundly despised. He is blamed often for Clinton’s 2016 loss, and denounced as a dangerous socialist, a narcissist obstructionist, even the Kremlin’s candidate. (Multiple Washington Post columns have claimed Vladimir Putin is pushing the Sanders campaign in order to help “elect Trump.”)

Sanders has obviously heard it all, along with the complaints about his age, 77, and other criticisms. These figured into the difficult calculation of whether to run. Unlike most candidates who finish second in a close presidential primary, he knew he would enter the next cycle as the opposite of a presumptive front-runner — more like a presumptive pundit scratching post.

But Sanders couldn’t afford to sit this out. Failure to run might have imperiled decades of efforts toward realizing ideas like Medicare for All and a raised minimum wage. He and many members of his staff also believe that on issues like climate change, the country can’t afford to wait out either another Republican or corporate-backed Democratic presidency. Ultimately, the calculation was no more message campaigns. Sanders not only has to run, he has to run and win.

Of course, to win, he’d essentially have to overturn the whole political system — two parties, big-dollar donors and the media. It’s his only realistic path to the presidency.

“It’s a different kind of campaign,” Sanders tells me in late April. “Look, we’re not just taking on Donald Trump. We’re also taking on the corporate establishment, the Democratic establishment, the drug companies, the health insurance companies, Wall Street. . . .

“It’s not just rhetoric,” he says.

WARREN, MICHIGAN. The day after the Madison rally, a much sunnier afternoon. A Detroit blues-acid-funk band called Act Casual blasts out “Hillbilly Disco” in the parking lot of Macomb County Community College.

Bernie 2020 events have a Monterey Pop feel, with audiences often full of rainbow tie-dye, picnicking families and toddlers running loose, all in odd contrast to the campaign’s legendarily square candidate. Everything from Brit pop to funk to reggae has warmed up Sanders events (I haven’t heard death metal yet, but maybe it’s coming).

It’s self-consciously a Sixties vibe, but defiant, Altamont-type Sixties, not the fuzzy Forrest Gumpversion. The campaign stokes this imagery in a ham-handed way by playing revolution-themed songs before the speeches start — “The Revolution Starts Now,” by Steve Earle, “Revolution,” by Flogging Molly, and so on.

Sanders’ revolutionary branding has always drawn eye rolls among people who take the word in its literal sense. Obviously, Bernie Sanders, perpetually tie-clad senator of a tiny dairy state, is not leading tunnel raids of Viet Cong or urging miners to dynamite coal tipples.

“There is nothing revolutionary about Our Revolution,” snapped the World Socialist Web Site in 2016, when Sanders launched a permanent organization after his campaign ended. The site ripped Sanders for working within the Democratic Party and failing to openly denounce capitalism.

Mainstream Democratic pundits similarly scoff at Sanders as an insurgent left phenomenon. Centrist barometer/pundit Jonathan Chait wrote a New York piece in February called “The Myth of Bernie Sanders’ White Working-Class Support,” claiming Sanders’ electoral success came significantly from the right — from “Never Hillary” voters, many of whom went on to vote for Trump and “had either left the party or had never been in it in the first place.”

“Without that protest vote,” Chait sniped, “the entire narrative of Sanders as the rising voice of the party’s authentic base would never have taken hold.”

The Sanders campaign’s point of view is that Bernie’s voters are the party’s authentic base, or at least were, once upon a time. The Macomb County event was chosen to make this point. This Detroit suburb is where Democratic pollster Stanley Greenberg coined the term “Reagan Democrats” four decades ago.

Greenberg was describing the predominantly white working-class voters who jumped to the Republican Party in droves in the Reagan years. Greenberg’s initial explanation, which became the traditional diagnosis among political scientists, was that these voters had been lured away mostly by racial appeals, over issues like busing and urban-renewal grants.

The Sanders campaign is betting on another take. They believe Democrats don’t have a problem with working-class white voters, but a problem with working-class voters of all races and backgrounds — lost to the party over the years due to frustrations with free-trade policies, a 50-year decline in real wages, disillusionment with bipartisan-supported foreign wars and their costs for military families, failure to regulate an increasingly exploitative financial-services sector, exploding incarceration rates and so on.

Craig Regester, an Ann Arbor professor and activist who introduces Sanders at the rally, hammers the theme when he takes the lectern. Regester says that when Reagan won here, political scientists “went crazy” trying to figure out what happened. Clearly referencing the race issue, he says, “They had all these theories, these elitist misunderstandings of the good and decent people who work and live in Macomb County. . . . What Bernie Sanders understands about what happened then, that no other Democratic candidate understands, is that those folks didn’t leave the Democratic Party. The party actually might have left them.”

Eventually, Sanders is introduced with his usual pop-revolution anthem, John Lennon’s “Power to the People,” the same intro tune of his last campaign (a song our own Hunter S. Thompson once dismissed as having been written “10 years too late”).

Dishing a few awkward Bern-shakes to crowd members on the way, Sanders ascends to the lectern and delivers much the same speech he gave in Madison — what one might call his Trump-is-a-pathological-liar speech, the essence of it being that “whether you’re a progressive, a moderate or a conservative, you are not proud that today we have a president of the United States who is a pathological liar.”

When Sanders mentions that Trump promised to be a “different kind” of Republican, you can hear a trace of Gilbert Gottfried as he deadpans, “It will not shock you to learn that he lied.” Occasional bone-dry sarcasm represents more or less Sanders’ full humor arsenal.

It all sounds on the surface like the same all-Trump-all-the-time rhetorical strategy that failed Democrats in 2016. However, it’s a little more nuanced. The constant references to working-class voters and the choice of places like Warren are an implicit indictment of past Democratic losses.

Sanders’ “revolution” may not be a beret-and-bayonet insurrection, but it is about using the vote to forcibly detach the Democratic Party from corporate donors, to return it to its roots as a labor-dominated organization.

The Blue Wall tour is crammed full of union imagery, with Sanders introduced at stop after stop by union leaders and advocates, who tell tales of the Vermont senator intervening in labor disputes, supporting strikes, joining picket lines, even being the first presidential candidate to unionize his staff. His union bona fides will be recited to the point of redundancy.

“Bernie Sanders is a union organizer,” United Electric worker and activist Alan Hart will tell one crowd. Sanders backed 1,700 striking workers this year at Hart’s old locomotive plant in Erie, Pennsylvania.

Sanders’ union-centric stump presentation is a surprisingly tight message for a candidate often criticized for being strategy-averse and who has already dealt with dissension and loss among his brain trust — three of his senior advisers have left the campaign since the launch.

“Obviously the issues of social justice are critically important . . . and we need to end discrimination in all forms,” Sanders tells me. “But we need a trade union movement to rebuild the middle class in this country.”

A drop in union support for Democrats was a little-discussed factor in the 2016 race. Exit polls showed union votes for Hillary Clinton fell about seven percent versus the Obama years.

Trump’s failure to keep promises to union members and/or bring back manufacturing jobs (although the rate of decline has slowed) might be a factor in swing counties in 2020, but it won’t be easy. There’s some evidence Trump’s tariffs, along with things like his generally hostile/insulting posture to China, still somehow carry weight with union voters. Democrats may only regain union votes if someone like Sanders — who probably went trick-or-treating as Samuel Gompers in his childhood — ends up on the ballot.

It’s been a while since any viable presidential candidate has described his or her campaign as part of a “trade union movement.” It may not be enough for the World Socialist Web Site, but an all-labor, no-corporate-money run is the closest thing to guerrilla politics you’ll see on an American campaign trail. It couldn’t actually work, could it?

Adam Brody, who works locally as a freight forwarder — that’s a person who organizes the logistics of moving goods and materials using “trains, boats, planes,” etc. — laughs at the question. “People thought Trump couldn’t win,” he says.

PITTSBURGH. Another big crowd, another string of fiery introductory speeches, including a couple from San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz and Nina Turner, the black former Ohio state senator who is an emerging leader in the nascent Democratic Socialist movement. Jill Stein asked Turner to be her running mate on the Green Party ticket in 2016, but Turner declined, saying, “I believe that the Democratic Party is worth fighting for.”

Today, as co-chair of the campaign, Turner is effectively Sanders’ unofficial running mate. She’s almost his rhetorical opposite: passionate, confident, off the cuff, able to say things like “hashtag-the-struggle-sho-nuff-real” and have crowds respond with something other than stunned silence.

In Pittsburgh, she takes the stage in a slick leather jacket (even when he was younger, Sanders couldn’t have pulled off a Starsky and Hutch look) and immediately riles up the audience: “Mayor Cruz and I, we’re bringing the co-chair girl power together, all right?”

Turner’s partnership with Sanders seems to work, but also draws attention to the undeniable fact that race has been a difficult issue for this campaign. Although Sanders talks a lot about social and racial equality, he has an almost Biden-esque propensity toward awkward foul-offs and maladroit responses when questioned on the topic.

In Houston earlier this year, at a She the People forum devoted to elevating women of color, Sanders was asked by host Aimee Allison what he would do to combat white-supremacist violence. After speaking about pushing an “agenda that speaks to all people” — a distant cousin of an “all lives matter” type of argument that Ebony called “dodging” the question — Sanders stepped on a verbal nail.

“I know I date myself a little bit here,” Sanders said, “but I was actually at the March on Washington with Dr. King back in 1963.”

The Houston crowd groaned, and it seemed aghast when he raised his trademark index finger to punctuate the observation. (The Bern Point is off-putting to some, amusing to others. There are versions of the Point that begin all the way to the candidate’s left or right and sweep across and down, almost like a disco move. If Sanders becomes president, college drinking games will surely be built around his pointing habits.)

Bernie Sanders will never be woke. Like Biden, he is an older white man who never could or would be able to see outside his own experience. The question will be if he’s doing enough to hit the right policy notes. As the campaign goes on, partners like Cruz and Turner will be instrumental in explaining what’s progressive about Sanders and his politics.

Turner especially seems to understand the difficulty of this mission and has become adept at filling in Bernie’s blanks. She delves into his personal story (Sanders often bends into Exorcist-style contortions when asked to talk about himself), sharing, for instance, his experience as the son of a Polish immigrant escaping the Holocaust. This ostensibly contrasts him with Trump’s infamous immigration stances. “Senator Bernie Sanders understands what it means to try to come to this country for a better life,” she says.

The Turner-Sanders partnership works best when Turner hits issues where she and Sanders have overlap. Like Sanders, she grew up in mean circumstances. From the age of 14, she worked in high-drudgery, low-reward jobs for profit-sucking fast-food chains and retail stores, which is probably why she shares Sanders’ naked disdain for such companies and any politician who takes their money.

“He won’t sell you out, and you can take it to the bank,” Turner says. “He can’t be bought off.”

All of the overt labor rhetoric at Sanders’ rallies makes it all the more frustrating that when Joe Biden, this election cycle’s version of the inevitable candidate, finally entered the race in late April, he did so with the backing of a firefighters’ union and United Steelworkers president Leo Gerard.

This is despite the fact that Biden is exactly the sort of Democrat that for decades has traded working-class votes for employer-class donations. Biden supported NAFTA, most-favored-nation trading status with China, and the Trans-Pacific Parnership — all anathematic positions for unions.

Biden even did his union-photo-op launch after a fundraiser at the home of David Cohen, an executive with Comcast, a company with a long record of opposing union organization and hiring nonunion subcontractors.

Biden’s schizoid approach is a perfect expression of the counterintuitive electoral dynamic between unions and Democrats. Dennis Kucinich, Dick Gephardt and Sanders in 2016 are on the list of longtime labor activists who’ve been stood up in presidential primary seasons by major unions in favor of Biden types.

“We went through this the last time,” says Sanders, who was endorsed by what he calls “three wonderful unions” in 2016, including the National Nurses’ Union. “But we did not have the support of a lot of the major unions.”

Sanders said he believes that the 2016 race caused union leaders to take “a lot of heat” from the rank and file for declaring for Clinton early. “I don’t think they’ll be so quick to decide this time,” says Sanders. “I don’t think there’s anyone who has a better record on unions than me.”

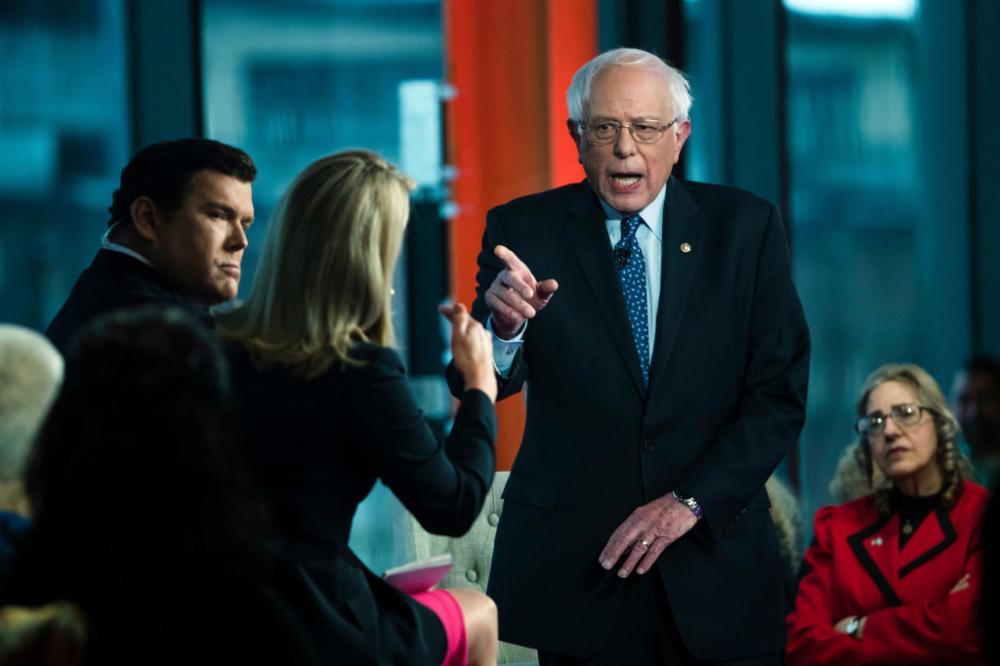

THE DAY AFTER the Pittsburgh event, Sanders has a live, Fox-televised town hall in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, a once-booming steel city and more recently famous as a capital of America Declining.

The sight of a self-described Vermont socialist taking quasi-polite questions from frontline Fox Satan-casters like Bret Baier and Martha MacCallum is surreal to the point where it’s surprising the hall doesn’t explode in hell flames. Baier in particular seems concerned his head might splatter, Scanners-style, every time he looks in Sanders’ direction.

When health care comes up, Baier asks for a show of hands, wondering how many people in the audience would be willing to transition to “what the senator says, a government-run system?”

Almost everyone raises their hands, and there are cheers in the hall. Vox later describes the scene as “Sanders 1, Fox News Hosts 0.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., takes part in a Fox News town-hall style event with Bret Baier and Martha MacCallum, in Bethlehem, PA. Photo credit: Matt Rourke/AP/REX/Shutterstock

As recently as the mid-2000s, it was considered a virtue for a Democrat to demonstrate the ability to “cross the aisle.” John Kerry’s introduction video at the 2004 Democratic convention even showed him with his arm around Arizona Republican and turgid Iraq War supporter John McCain.

In the Trump era, “crossing the aisle” is about as popular among blue-state intelligentsia as scabies or snuff films. No effort to court the Fox audience is considered kosher. In a year when Democrats officially cut off Fox as a debate broadcaster, Sanders’ decision to do the town hall was a political act in itself. Did it accomplish anything?

“Fox was kind enough to let us write an editorial after that,” Sanders says. “I think there are a few people who watched who are working two to three jobs, who have nothing set aside for retirement, and they’re wondering: Who cares about us? Do Democrats care about us? Do Republicans care about us?”

He pauses. “I think there are some working-class people out there who will say, ‘I don’t agree with Sanders about everything, but he’s right.’ ”

Whether or not you believe his pitch will work depends a lot on whether you think Trump’s voters were misled, or whether they read him loud and clear and voted out of racial and cultural resentment rather than the economic issues Sanders holds dear.

The official entrance of Biden soon overwhelmed the novelty of Sanders’ Fox appearance. Early polls put him ahead of Sanders by as many as 20 points and the same pundits who called the 2016 race prematurely on both sides of the aisle were quick to pronounce the primary all but over. The 2020 race will be compared to 2016 in large part because the preposterous (at press time) 21-candidate Democratic field has such obvious parallels to the 17-person “Clown Car” GOP field last time.

This race has already seen headline blizzards for California Sen. Kamala Harris, Texas congressman Beto O’Rourke and South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, and debates haven’t even started. A lot of these press freakouts appear as thinly disguised Beltway prayers for someone to knock Sanders out of the race. The Washington Post openly wrote that Buttigieg might “save the Democratic Party”from the Vermont senator. No other candidate inspires these takes: Pundits don’t gush when Harris drops in the polls, for instance.

Sanders seems to know it. Talking to Rolling Stone in the days after Biden’s much-ballyhooed jump into the race, he sighs. He’s clearly exhausted by it all, intellectually if not physically.

Still, anyone who’s followed this politician for any length of time knows that both the strength and weakness of Sanders is his relentless sameness. Over and over again, across more than 40 years in public life, he has been saying essentially the same thing — staffers affectionately refer to his decades-long clarion call about siding with working people against corporate power the “Berniefesto.”

Sanders doesn’t have Ted Cruz episodes, where a thousand speeches into a campaign, he suddenly feels a need to burst into Princess Bride impersonations. Sanders has only one note, and deviating from it never occurs to him. What Turner says about Sanders never being bought off is true, if only because if the senator tried to sell out, he wouldn’t know where to start and would suck at it. He’s also never tried shutting up, and probably couldn’t do that, either.

So he’s in for the long haul. Acknowledging that campaigns have highs and lows, he shakes off the media furors and points to the volunteers counting on him. “We just had a weekend with 4,700 house parties, with over 70,000 people attending,” he says. “That’s an unprecedented level of involvement, and it’s in every state. We’re going to do our best.”

Some outside observers will say he’s already had his impact, by mainstreaming ideas like Medicare for All. Fifty-six percent of all Americans and as many as four out of five Democrats now support single-payer health care.

Even Max Baucus, the former Democratic Senate Finance Committee chairman who was essentially the public-option killer during the Affordable Health Care Act fight in the Obama years, said after the 2016 race “the time has come” to consider single-payer. Similarly, many of the 21 Democratic candidates are for some version of Medicare for All.

The 30,000-foot pundit view on Sanders’ chances should be that he, of course, has a chance, one rooted in the same logic that saw Trump win. He is an unconventional candidate with an at least somewhat insoluble base of support, running in an overlarge field of mostly traditional politicians, many of whom will take votes from one another.

For Sanders to win, all his voters have to do is overthrow basically the entire political system, which would be ridiculous except that all the other options may be worse: Trump is no solution, and a seemingly mighty traditional Democrat fell short last time.

Moreover, if 2016 taught us anything, it’s that press pronouncements are often an anti-indicator on electability questions. Should any of the “inevitable” candidacies stumble, a plurality of votes might carry the day, as it did for Trump three years ago. Then and only then will we find out if Bernie’s pitch to the working class was really a revolution, or just another song written too late.

Matt Taibbi is a contributing editor for Rolling Stone and winner of the 2008 National Magazine Award for columns and commentary. His most recent book is ‘I Can’t Breathe: A Killing on Bay Street,’ about the infamous killing of Eric Garner by the New York City police. He’s also the author of the New York Times bestsellers 'Insane Clown President,' 'The Divide,' 'Griftopia,' and 'The Great Derangement.'

Spread the word