Filiberto Morales was 36 years old when he reported to work at a construction site on the grounds of Coryell Memorial Hospital in Gatesville, Texas. It was June 26, 2018. According to an investigative report from the state fire marshal’s office, as Morales was working in the site’s mechanical room, natural gas was leaking into the area from nearby pipes. When a spark in the neighboring boiler room ignited the gas, the structure exploded. Morales survived the blast but died two days later. He had suffered blunt force trauma to the head. Morales left behind a son and wife he married six months before the accident.

Two other workers were killed. Michael Bruggman, who was on the roof of the site, died instantly. Wilber Dimas, who was working in the boiler room, suffered burns to 70 percent of his body and died on July 15, 2018. In total, the state report notes three were killed and 13 were injured as the debris field from the explosion extended 1,100 feet from the blast.

This is the story of three workers out of potentially millions who died or reported illnesses or injuries on the job in 2018. While the Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t yet have statistics for 2018, 5,147 workers died and 3,475,900 workers were injured or became ill on the job in 2017. Out of those killed, 41 percent died during vehicular and transportation operations and 20 percent during constructing, repairing or cleaning activities. According to a 2019 report by the AFL-CIO, these numbers are likely conservative as “under-reporting is widespread.”

The agency responsible for keeping track of reporting is the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). In 1970, Congress passed the Occupational Safety and Health Act and established OSHA within the Department of Labor. The agency’s purpose, as expressed in its mission statement, is to “ensure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women by setting and enforcing standards and by providing training, outreach, education and assistance.”

To this end, OSHA handles workplace inspections and upholding safety standards through citations and penalties. For example, in the case of the accident at Coryell Memorial Hospital, OSHA fined a subcontractor, Lochridge-Priest, Inc., $12,934. The citation stated:

The employer did not furnish employment and a place of employment which was free from recognized hazards that were causing or likely to cause death or serious physical harm to employees, in that, employees were exposed to fire and explosion hazards. In the boiler room area of the jobsite, employees purging air from natural gas lines without using a combustible gas detector, exposing the employees to fire and explosion hazards.

A fine of less than $13,000 for an accident that cost three lives may seem on the low end, but it is actually on the high end. In fact, it is the high end. According to the AFL-CIO, the latest change to federal OSHA penalties for serious violations, which is how the agency classified the Coryell accident, bumped the maximum fine to $13,260. For repeated or willful violations, the fine is $132,598.

The AFL-CIO report notes that federal OSHA fines for serious violations averaged $3,580 in fiscal year 2018. For state OSHA plans, that number was $1,985. As the AFL-CIO mentions in its report, “State plans also are required to raise their statutory maximum penalties in order to be as effective as the federal OSHA program, but to date, not all states have complied.”

The number of serious violations issued by federal OSHA has fallen from 74,721 in 2010 to 36,365 in 2018. While that might imply work sites have gotten safer, other data suggest otherwise. The fatality rate — defined here as the number of deaths per 100,000 workers based on the annual average of workers ages 16 or older — has remained around 3.3 since 2010. It’s possible workers fear losing their jobs and are less likely to report violations. Programmed or precautionary inspections initiated by the agency have fallen from 24,752 in 2010 to 13,980 in 2018, while inspections conducted due to complaints have basically remained the same. This is likely due to the fact that the number of compliance officers, who conduct these inspections, has been on a steady decline for decades.

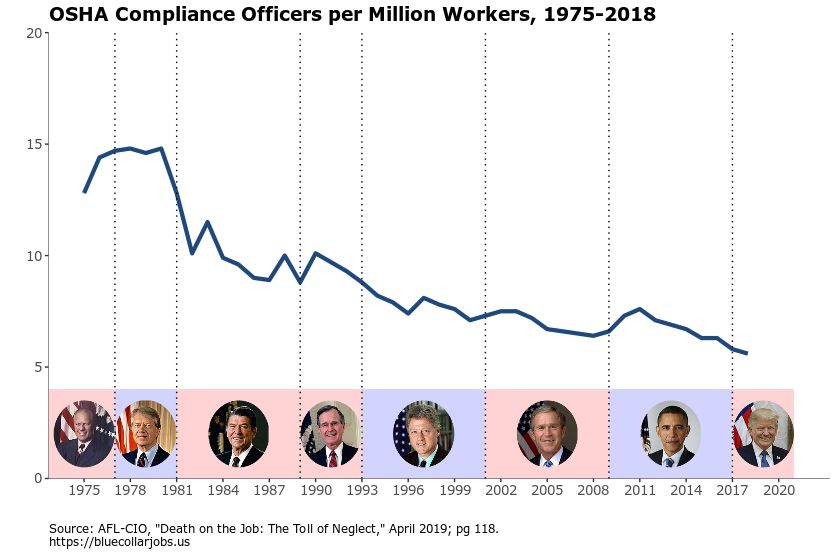

To understand how we got here, you have to look at the agency going back to shortly after OSHA was established in 1971 under President Nixon. Between 1978 and 1980, as the agency grew, it had approximately 14.8 compliance officers per million workers at the federal level. As the workforce grew, however, various administrations and Congress failed to meet the demand for more inspections. The steepest drop occurred under Presidents Reagan and H.W. Bush, but later administrations did little to reverse that trend. Under President Trump, the number of inspectors has reached its lowest level since the early 1970s.

While the Trump Administration is not solely responsible for the state of OSHA’s enforcement capabilities, it certainly hasn’t helped by weakening the agency’s ability to regulate health and safety standards. OSHA under the Trump administration has:

- Repealed rules that clarify the responsibilities of employers to keep accurate injury and illness records and require large employers to electronically submit detailed, publicly-available reports to OSHA.

- Postponed a rule introduced during the Obama Administration that would’ve required employers to take measures that minimize workers’ exposure to beryllium dust, which has been linked to cancer.

- Rolled back worker safety protections, specifically on the Mine Safety and Health Administration’s mine inspection rule and the regularity of testing equipment on oil rigs.

Further, Trump’s 2018 budget attempted to cut $2.5 billion from the Department of Labor, including an $11 million OSHA training grant program. And for the 2019 and 2020 budgets, he again targeted the Department of Labor for major cuts. To date, Trump has not nominated an assistant secretary for OSHA, and two positions on the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission, which holds hearings and renders decisions on appeals to citations or penalties issued as a result of OSHA inspections, remain vacant. Trump’s populist messages of bringing back jobs and making America great again are at odds with his actions.

It’s unrealistic to say that what happened at Coryell never would have occurred if OSHA hadn’t been weakened by decades of bad policies and politics. But there are thousands of accidents like Coryell across the United States every year that could be prevented by stronger safety and health regulations and enforcement. America needs an OSHA that puts workers, not business’ bottom lines, first.

It should be noted that’s not the only sanction the companies may face over the accident. Wilbur Dilmas’ mother filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Atmos Energy Corp., Lochridge-Priest, Inc., and Johnson Controls, Inc. The hospital also filed a lawsuit against the general contractor, Adolfson & Peterson Inc., and Zurich American Insurance Company.

While OSHA covers private and public sector workers in every state and jurisdiction within the U.S., 22 states operate State Plans, which are approved and monitored by OSHA. The rest of the states fall directly under federal OSHA.

Matt Sedlar holds a BA in Communications and minor in Political Science from the University of California, Fullerton, and certifications in data journalism and data science from the European Journalism Centre and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, respectively. He is currently working toward an MA in Sociology at George Mason University. Prior to working with CEPR, Matt worked as a web communications specialist for SEIU-UHW in California, as well as at various news organizations.

Mark Weisbrot and Dean Baker founded the Center for Economic and Policy Research in 1999 with a total budget of less than $120,000. From its humble beginnings, CEPR has grown in both size and stature. The reason? CEPR's independent research successfully challenges conventional wisdom and identifies economic trends long before the economics profession has noted them.

CEPR has been ahead of the curve in tackling a range of issues:

● Starting in 1999, CEPR economists were in the frontline fighting to oppose privatizing Social Security.

● CEPR’s Dean Baker has been widely recognized as the first economist to correctly analyze both the stock market and housing bubbles that caused, respectively, the last two recessions.

● CEPR has led efforts to make the Federal Reserve abide by its mandated pro-worker policies.

● CEPR has played an indispensable role in promoting accountability in foreign economic policy, including the most important institutions of global governance (the IMF and WTO).

● CEPR has played a leading role in the public debate on the role of intellectual property, macroeconomic policy, digital global trade, and international commercial agreements on inequality and economic mobility.

Donate to the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR).

Spread the word