There is a common stereotype among black and white Americans, and it’s that black people don’t vote.

During his 2016 keynote address at the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, Barack Obama went so far as to say: “Even if all restrictions on voting were eliminated, African Americans would still have one of the lowest voting rates. That’s not good. That is on us.’” On the other end of the spectrum, Trump insinuated that black voters stayed home during the election. “They didn’t come out to vote for Hillary. They didn’t come out… so thank you to the African American community.”

The same message reverberated through political commentary and activism. Brando Starkey of The Undefeated wrote that, “Black people who didn’t vote let us down,” in the 2016 election. Two years later, the Detroit News’ Bankole Thompson wrote, “It is not enough to raise your fist in a political frenzy as a symbol of Black power and solidarity if you are failing to exercise the power of the ballot and not showing up at the polls.”

Despite these comments, “black people don’t vote” is not based in data: though they are only 13% of the US population, black voters are among the most stable voting bloc in politics, despite the concerted efforts to stop them. The myth, instead is rooted in an exaggerated narrative derived from Reconstruction-era stereotypes about work ethic, opportunity and culpability. Similar to how black people were the economic scapegoat for the downfall of southern states once slavery was outlawed, they also became the political scapegoat for the losses of the Republican party in the late 1800s.

After the civil war, black voter turnout boomed and elected nearly 20 black people to the House and Senate and many more to local and state positions. By December 1887, however, Congress convened without one black member in about two decades leading to “The Negroes Temporary Farewell” when black people were excluded from Congress.

As black people gained political power during Reconstruction, southern states passed stringent voter ID laws and gave black people voting literacy tests that included outlandish questions such as: how many plies are on a roll of toilet paper or how many bubbles does a bar of soap have? Some were even lynched for voting or asking for the right to vote.

Black people became disenchanted with the Republican party and some started to align with the civil rights arm of the Democratic party as Jim Crow continued to disenfranchise them. Once the 15th amendment was restored during the civil rights movement, black people instantly became a strong voting bloc for the Democratic party, particularly in the south.

When Democrats lose, however, it is the same stereotype – black people didn’t come out to vote. But in the last three presidential elections, black voter turnout was 59.6% in 2016, 66.6% in 2012, and 65.2% in 2008. The voter turnout for black people in each of these elections was higher than Latinos and Asians and higher than whites in 2012.

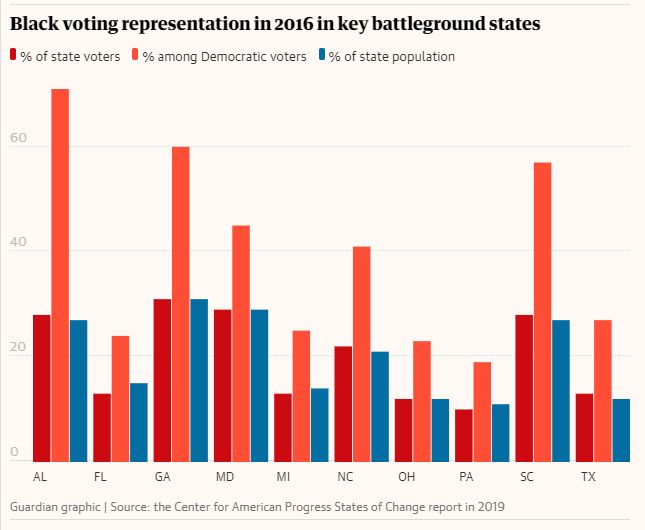

Of the 10 states highlighted in the graph, black voter turnout in seven of these states in 2016 was higher or the same as their percentage of the state. In five states, black people represented over 40% of Democratic voters in 2016.

While it is true that black voter turnout decreased from 2012 to 2016, it does not mean that black people are to blame for the Democratic loss of the 2016 election. Twelve percent of whites who voted for Obama in 2012 voted for Trump in 2016. Considering Hillary Clinton lost by less than 11,000 votes in Michigan and 44,000 votes in Pennsylvania, these changes made a difference too.

Despite the apparent preference for voting Democrat, black voters are not a monolith. Gender, education and incarceration are factors in determining voter turnout and political party preference. Generally, women vote at higher rates than men across race, and this is true of black women too. And, while most black women with or without college degrees voted for Hillary Clinton, only 78% of black men with a college degree (16% voted for Trump) and 82% without a college degree voted Democrat (11% voted for Trump).

This data still doesn’t tell the whole story. Current barriers to voting are real, pervasive and covert. In 2013, the decision in the Shelby county v Holder case afforded people who want to disenfranchise black people the license to do so. Incriminating documents were found on the hard drive of a Republican operative known as the “gerrymandering king” who deliberately drew new political maps to dilute the black vote in North Carolina. Nearly 900 polling places were closed from 2012 to 2016, including over 400 in Texas and nearly 40 in the Carolinas.

There are also the 6.1 million people disenfranchised due to felony convictions. About 40% of this group is black. This means one of every 13 black people cannot vote due to voter disenfranchisement.

We have to challenge the stereotypes and assumptions we make about each other and recognize that real barriers to voting continue to persist but are surmountable. If we really want to create racial equity in the political process so that all Americans can truly embrace American democracy, The Voting Rights Act will be fully restored and expanded, the Shelby v Holder decision will be revisited to prevent gerrymandering, millions of returning citizens will have their voting rights restored, and election day will become a federal day of service to remove barriers related to employment.

Dr Rashawn Ray is a David M Rubenstein fellow in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution, an associate professor of Sociology at the University of Maryland, and the executive director of the Lab for Applied Social Science Research. He is on Twitter at @SociologistRay

America faces an epic choice...

... in the coming year, and the results will define the country for a generation. These are perilous times. Over the last three years, much of what the Guardian holds dear has been threatened – democracy, civility, truth. This US administration is establishing new norms of behaviour. Rampant disinformation, partisan news sources and social media's tsunami of fake news is no basis on which to inform the American public in 2020. Truth is being chased away. But the Guardian is determined to keep it center stage.

More readers in the US than ever before are reading and supporting the Guardian’s independent, fact-based journalism. We now have supporters in every state in America. The need for a robust press has never been greater, and with your generous help we can continue to provide reporting that offers public scrutiny and oversight. And, together, we can help the truth triumph in 2020.

"America is at a tipping point, finely balanced between truth and lies, hope and hate, civility and nastiness. Many vital aspects of American public life are in play – the Supreme Court, abortion rights, climate policy, wealth inequality, Big Tech and much more. The stakes could hardly be higher. As that choice nears, the Guardian, as it has done for 200 years, and with your continued support, will continue to argue for the values we hold dear – facts, science, diversity, equality and fairness." – US editor, John Mulholland

On the occasion of its 100th birthday in 1921 the editor of the Guardian said, "Perhaps the chief virtue of a newspaper is its independence. It should have a soul of its own." That is more true than ever. Freed from the influence of an owner or shareholders, the Guardian's robust editorial independence is our unique driving force and guiding principle.

We also want to say a huge thank you to everyone who has supported the Guardian in 2019. You provide us with the motivation and financial support to keep doing what we do. We hope to surpass our goal by early January. Every contribution, big or small, will help us reach it. Make a year-end gift from as little as $1. Thank you.

Spread the word