President Trump is all in, touting his success in rebuilding US manufacturing. For example, in his state of the union address he claimed:

We are restoring our nation’s manufacturing might, even though predictions were that this could never be done. After losing 60,000 factories under the previous two administrations, America has now gained 12,000 new factories under my administration.

Apparently, it is a family achievement. Joe Ragazzo, writing at TPM Café, reports that:

In a towering act of sycophantry, the National Association of Manufacturers announced Friday that it will be giving Ivanka Trump the organization’s first ever Alexander Hamilton Award for “extraordinary support of manufacturing in America.” The organization made the outrageous claim that “no one” — no one! — has ever “provided singular leadership and shown an unwavering commitment to modern manufacturing in America” like she has.

Unfortunately, US manufacturing is far from healthy.

Production

The reality is that manufacturing output has been relatively flat over the last two decades, thanks in large part to the globalization of US production. In 2019, despite the growth of the overall economy, the manufacturing sector actually fell into recession. In contrast to Trump’s claim, manufacturing output fell 1.3 percent over the year.

The figure below shows real manufacturing output indexed to 2012. We see slow but steady growth from 2000 to 2007, relatively flat growth from 2010 to 2018, and then a decline in real output in 2019.

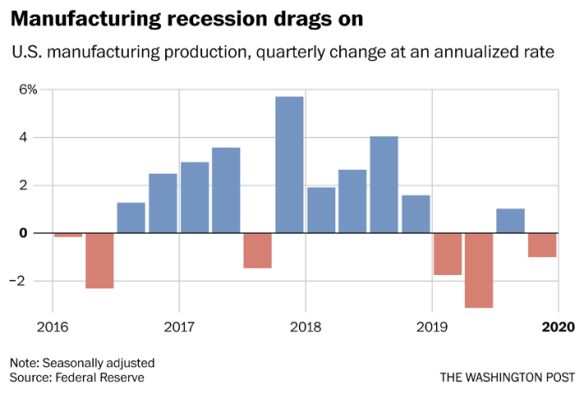

The manufacturing sector’s woes in 2019 are on display in the following figure.

Investment

In line with these trends, as we can see below real investment in new structures by manufacturing firms has also been falling. Real investment fell from $73.7 billion in 2015 to $56.4 billion in 2019.

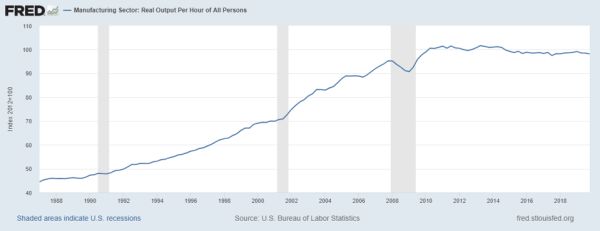

Manufacturing productivity is at a standstill. The following figure shows manufacturing output per worker hour, indexed to 2012. As we can see, it was largely unchanged from 2010 to 2014. Since then it has trended downward.

Employment

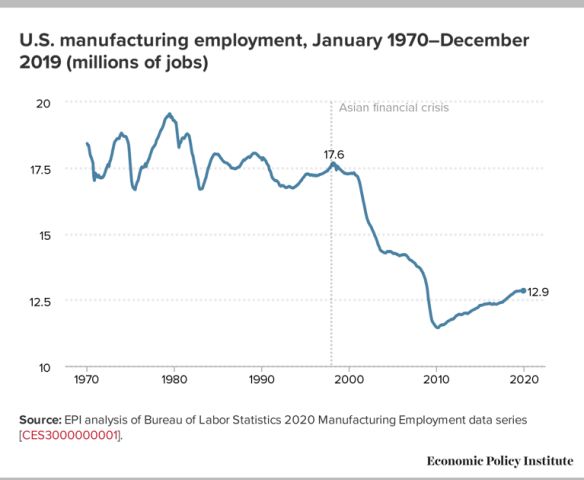

The employment story is even worse. As the next figure shows, manufacturing employment, in millions of jobs, took a nose dive beginning in the late 1990s and has yet to make a meaningful recovery.

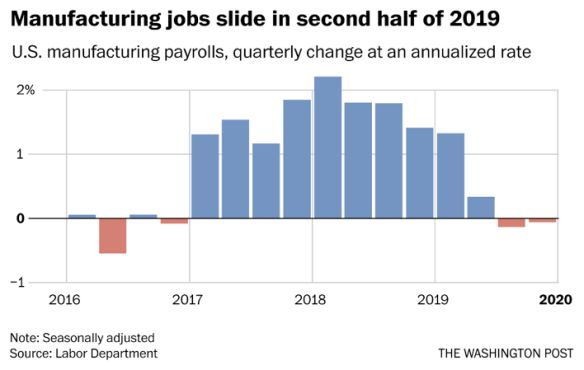

Some 5 million manufacturing jobs have been lost since the late 1990s. Nearly 90,000 U.S. factories have been lost as well. And in line with manufacturing’s current recession, manufacturing employment, as we see below, is again falling.

Earnings

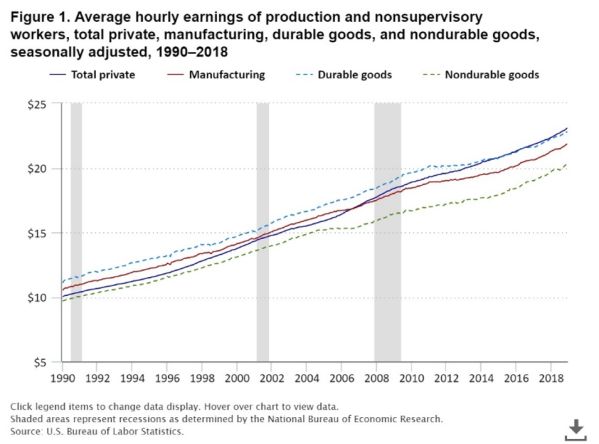

Equally alarming, the average hourly earnings of production workers employed in manufacturing has now fallen below the average hourly earnings of private sector production and nonsupervisory workers. Thus, even if US policy were to succeed in bringing back or spurring the creation of new manufacturing jobs, they likely won’t be the living wage jobs of the past.

As the Monthly Labor Review explains:

Although manufacturing industries had a reputation for stable, well-paying jobs for much of the 20th century, shifts within the industry in the last several decades have considerably altered that picture. Since 1990, average hourly earnings trends in the various manufacturing industries have been disparate, with a few industries showing strong growth but many others showing growth rates that are lower than those of the total private sector. In fact, average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory workers in the total private sector have recently surpassed those of their counterparts in the relatively high-paying durable goods portion of manufacturing.

As we can see in the following figure, in 1990 average hourly earnings of production workers in manufacturing were greater than those of production and nonsupervisory workers in the total private sector (by about 6 percent.) However, by 2007, average hourly earnings in the private sector had surpassed average hourly earnings in manufacturing. And by 2015, average hourly earnings in the private sector surpassed average hourly earnings of manufacturing workers in the more highly compensated durable goods sector. In 2018, the average hourly earnings of private sector production and nonsupervisory workers was approximately 5 percent greater than those of their manufacturing counterparts.

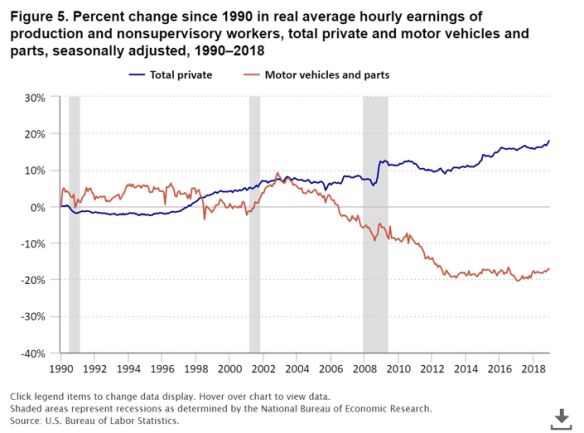

Workers in the auto industry have especially taken a big hit.

Trade

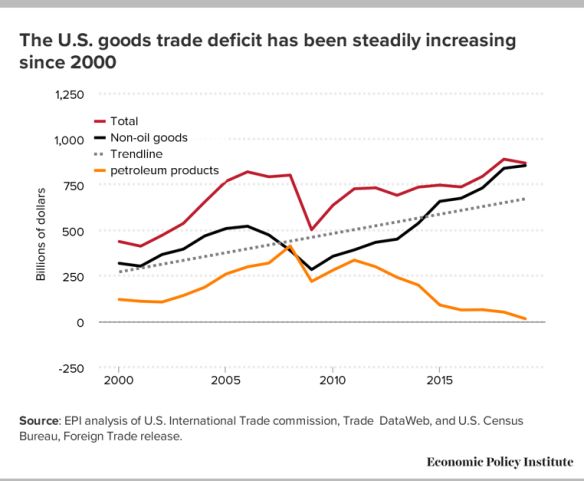

The overall trade deficit, which reflects the combined balances on trade in goods and services, slightly improved in 2019—falling by 1.7 percent or $10.9 billion. So did the deficit in the trade of goods, falling by 2.4 percent or $21.4 billion. However, those improvements were mostly driven by the rapid growth in US exports of petroleum products. The trade deficit in non-oil goods, mostly manufactures, actually increased by 1.8 percent in 2019, as can be seen in the following figure.

As Robert E. Scott remarks,

The small decline in overall US trade deficits follows an 18.3 percent increase in the goods trade deficit in the first two years of the Trump administration. Taken altogether, the US goods trade deficit increased $116.2 billion (15.5 percent) in the first three years of the Trump Administration. . . .

Meanwhile, the deficit in non-oil goods trade has nearly tripled since 2000, rising from $317.2 billion in 2000 to $852.3 billion in 2019, an all-time high. For the past two years, the non-oil goods trade deficit also reached record territory as a share of GDP, reaching or exceeding 4.0% of GDP. This growing U.S. trade deficit in non-oil goods is largely responsible for the loss of 5 million U.S. manufacturing jobs since 1998.

As we can see, talk of a manufacturing renaissance is nonsense. And there is no reason, based on Trump administration’s economic policies, to expect one.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is Professor Emeritus of Economics at Lewis and Clark College, Portland, Oregon and Adjunct Researcher at the Institute for Social Sciences, Gyeongsang National University, South Korea. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the Korea Policy Institute and the steering committee of the Alliance of Scholars Concerned About Korea. He is also a member of the Executive Board of Portland Jobs With Justice and the organizing committee of the Workers’ Rights Board (Portland, Oregon).

Spread the word