Black History Month, if treated seriously, could help clarify a key point about race in America: African Americans were created by slavery. As I argued in 2006:

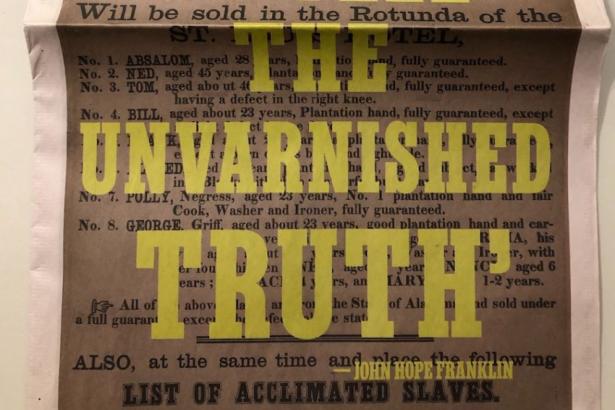

Millions of Africans wound up in America only because they were kidnapped to fill the needs of a slave economy. This process forged a new people, who became American by necessity, and included 12 generations of chattel slavery.

This history of slave—rather than racial—identification accounts for the disadvantages accrued by the progeny of enslaved Africans. With this understanding, the culpability for redressing that specific legacy rests on the government that abetted it.

My 2006 piece noted that affirmative action was, at first, created to compensate the victims of slavery’s legacy—but “other groups had to be included to gain political support … affirmative action became a comprehensive attempt to offset discrimination against all ‘minorities.’ ” The resulting practice meant that a business exercising affirmative action could employ many people of color without hiring a single African American. That affirmative action has diverged so dramatically from its initial conception is yet more proof of this nation’s reluctance to face the truth of its ignoble, Afrophobic history.

The issues I raised in 2006 rose to the surface of public discourse in 2019 in two major ways. The New York Times Magazine embarked on something it called “The 1619 Project,” named to mark the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans to the shores of Virginia in what would become the United States. Spearheaded by Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones, the project’s goal was “to reframe American history by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year. Doing so requires us to place the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are as a country.” Such an audacious conception—in the Times? As I read through the special issue, I found a new awareness of how the legacy of slavery is thoroughly interwoven with America’s founding precepts. The recognition seemed too good to be true.

Despite predictable grumbling from conservative quarters and some academic salons, the response to the project has been overwhelmingly positive. The Times supplement quickly sold out. What’s more, school districts in Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Buffalo, N.Y., (among a growing number) have incorporated material from the project into their curricula.

Reparations, too, has burst into public view. In summer 2019, the House held its first hearing on H.R. 40, a bill that would create a commission to develop proposals to address and redress the legacy of slavery. The bill had been introduced by the late Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.) in each House session since 1989—where it languished, unattended—but this hearing attracted, among others, actor/activist Danny Glover and author Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose 2014 essay in The Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations,” gave the concept an infusion of intellectual credibility. Early in the 2020 Democratic campaign, several candidates, urged on by candidate Marianne Williamson (who since has dropped out), expressed support.

While the discussion of reparations has died down again, its emergence in public discourse is another sign that the legacies of slavery—housing discrimination, wealth inequality, educational disadvantage—are being treated with new urgency. This refined perspective on our nation’s history directly connects slavery to the ongoing socioeconomic status of slavery’s victims. Finding data to trace the multigenerational path of these wrongs has become a new mission for historical researchers.

Thankfully, these new developments surrounding the conversation about race in America inject a shot of badly needed relevance into the often restrained observance of Black History Month.

Salim Muwakkil is a senior editor of In These Times, where he has worked since 1983. He is the host of The Salim Muwakkil show on WVON, Chicago's historic black radio station, and he wrote the text for the book HAROLD: Photographs from the Harold Washington Years.

Reprinted with permission from In These Times. All rights reserved.

Portside is proud to feature content from In These Times, a publication dedicated to covering progressive politics, labor and activism. To get more news and provocative analysis from In These Times, sign up for a free weekly e-newsletter or subscribe to the magazine at a special low rate.

Never has independent journalism mattered more. Help hold power to account: Subscribe to In These Times magazine, or make a tax-deductible donation to fund this reporting.

Spread the word