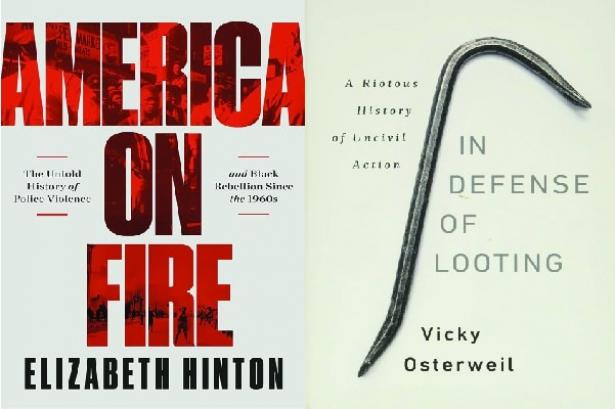

The Ballot or the Brick: On Elizabeth Hinton’s ‘America on Fire’ and Vicky Osterweil’s ‘In Defense of Looting’

In Defense of Looting: A Riotous History of Uncivil Action

by Vicky Osterweil

Bold Type Books, 2020, 288 pp.America On Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s

by Elizabeth Hinton

Liveright, 2021, 408 pp.

In 2007, the socialist historian Michael B. Katz marked the fortieth anniversary of the “Long, Hot Summer” with a puzzle. In the forty years since that wave of Black rebellions rocked the country, urban inequality had only worsened. Decent jobs had become rarer, public housing more dilapidated, the racist lethality of police more visible thanks to camcorders and camera-phones. Yet U.S. cities had not witnessed anything like the sustained insurrection of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Why weren’t U.S. cities burning?

Katz passed away on August 23, 2014, two weeks after the Ferguson rebellion began. Six years later, the United States witnessed the largest collective uprising in its history. The public execution of George Floyd and the killing of Breonna Taylor ignited what those on the left have called a “Black led multiracial rebellion,” a “militant nationwide uprising” and a “revenge against property and the state.” The specter of 1967 had returned.

Two recent books, completed on either side of the 2020 uprising, enable us to consider the relationship between the present conjuncture and past Black revolts. Elizabeth Hinton’s America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s and Vicky Osterweil’s In Defense of Looting: A Riotous History of Uncivil Action argue that the Black freedom struggle reached its apex during the urban uprisings of the 1960s and early 1970s. Each author seeks to do more than simply generate sympathy for rioters by insisting on the righteousness and effectiveness of rebellion. These improvised acts of violence and looting do not fit the dominant narrative of a “nonviolent” civil rights. Neither do they make sense as the disciplined violence of armed struggle most closely associated with the Black Panther Party in this period. Read together, these books may be the spark of something new: what we might call a political history of the brick.

These books are powerful ammunition for today’s anti-racist scions, dry powder for the next phase of battle. And yet, each raises a vexing question: As twenty million people took to the streets in 2020, why did so few pick up a brick? And would the movement to which they belong be better off if they had?

In Defense of Looting makes an impassioned case for the righteousness and efficacy of violence. The book grew out of the flames of Ferguson—“the most militant sustained struggle” since the Civil Rights Movement. In August 2014, Osterweil wrote an essay of the same title for The New Inquiry arguing for “not-non-violent” tactics. The book-length version could not be timelier. According to a postscript, Osterweil submitted her manuscript on May 29, 2020. The day before, protesters set a Minneapolis police station on fire. “I have no idea what political world this book will emerge into,” Osterweil marvels, “and that’s beautiful.”

The book is aimed less at conservatives—whose allegiance to law-and-order is unwavering—than to liberals who claim to be on the side of justice. Riots, to use words deployed by liberals since Lyndon Johnson, are the products of “outside agitators,” opportunism, and basic greed. Osterweil’s introduction attacks this view that looting is inherently wrong and politically unwise. If rioters are not part of the movement, “why do they appear again and again in liberatory uprisings?” Rather, the left should heed “the wisdom and power of the Black revolutionary tradition.” “The future is ours to take,” she urges. “We just need to loot it.”

Osterweil’s case for looting begins by recognizing—as Marx did—that property is itself founded on violence. The book’s early chapters consider the role that stolen land and enslaved labor—twin “pillars of racialized dispossession”—have played in the country’s development. Acknowledgement of the United States as a settler colony rooted in slavery has grown in recent decades, but Osterweil casts these themes in a new light. With the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, she writes that slaveholders codified their right to “loot” free Blacks. And like many tactics, looting worked both ways. During the Civil War, two million enslaved persons fled the Confederacy in what W. E. B. Du Bois influentially regarded as a general strike. Osterweil suggests this tactic was also a form of looting: abolishing the self-as-property. With emancipation, $3 billion of wealth disappeared from the nation’s financial ledgers. Here was two-thirds of GDP, looted overnight.

It took work to ensure the exploitation of land and labor. Osterweil follows historians who argue that early police formed to control the movement of emancipated Blacks and unruly workers. Professional police emerged in the late nineteenth century to manage the upheavals of mass migration, labor militance, and interracial democracy. Because police enforce inequality, looting is necessarily an attack on the legitimacy of policing. By assembling so many disparate struggles under the rubric of “looting,” Osterweil reveals vivid moments of resonance. For Osterweil, the Charlotte protesters who overturned semi-trucks in 2016 recall Gilded Age saboteurs who used the boss’ railcars as flaming barricades against the cops. Today’s militants have history on their side.

The Civil Rights Movement is the key turning point in Osterweil’s narrative. In Defense of Looting assails the Whiggish story told “by presidents, professors, and police chiefs alike” in which an interracial movement triumphed using nonviolence. Osterweil instead dismisses “nonviolent resistance” as “incredibly nebulous” and “murky.” The movement’s zenith was not the Civil Rights Act of 1964, she argues, but the conflagrations that followed. As inner cities from Watts to Newark burned, they exposed the gap between “liberal declarations of victory” and the “lived experience of Black people.” For Osterweil, violence brought the movement the closest it came to victory: a “revolutionary strike against white supremacy.”

Here Osterweil’s argument outpaces the historical record. It’s true that for civil rights activists, the use of nonviolence could be more strategic than normative. Martin Luther King traveled with a heavily armed entourage. Despite her calculated image as a dowdy old woman, Rosa Parks idolized Robert F. Williams, whose memoir-manifesto Negroes with Guns inspired the Black Panthers. More importantly, Osterweil is right to insist on the late 1960s as a moment of political possibility. And yet the counterfactual history presented by In Defense of Looting is not supported by the evidence. Osterweil believes that riots necessarily “transform the consciousness of their participants,” turning the urban lumpen into an anti-capitalist vanguard. In historical terms, it’s unclear how the uprisings of the late sixties could have developed into an outright revolution. Osterweil appears to blame would-be revolutionaries for this failure: “Without increasing street action,” radicals “fell to repression, fizzled out, or devoured themselves through splits and infighting.” Osterweil does not suggest what form this escalation should have taken. What room was there for heightened “street action,” as hundreds of cities burned?

The strength of In Defense of Looting is Osterweil’s ability to cut through liberal moralizing to take violence on its own terms. “As much as any of us can, rioters and looters know exactly what they’re doing,” she writes. But like many of us who witness or participate in these forms of protest, Osterweil tends to see what she wants to see in the crowd. Consider her use of Jackie Wang’s 2014 essay “Against Innocence,” which argues that describing victims of oppression as innocent forecloses universal demands for justice. Osterweil does not engage with the essay’s section on antipolice riots, in which Wang criticizes the assumption that rioters necessarily share a clear political consciousness. For Wang, the supposed purity, even primitivism of the rioter is the white left’s own appeal to “innocence.” Osterweil aims to restore looting to “the romantic stuff of revolutionary fantasy.” Wang shows the hazards of such fantasies in the first place.

Despite its title, In Defense of Looting is less an apologia for rioting than a case for its tactical supremacy. Nonviolence “lets the police, and the systems that they defend, off the hook.” Political parties, non-profits, and labor unions: these have only dampened popular dissent. Only looting offers “a practical, immediate form of improving life” for the urban dispossessed. Ultimately, failing to use violence means capitulation. Osterweil describes a hypothetical protester who fails to prevent another’s arrest: “I believe this demonstrates a much deeper complicity with violence,” she writes, than it would “to shove a cop” and “let that person get away.”

But is the choice really between scuffling with cops and doing nothing? In Defense of Looting substitutes adventurism for anti-capitalist strategy. The person in zip-cuffs does not need more people willing to “shove a cop.” They need a bail fund, a legal hotline, and someone to phone their friends. They need the police to be defunded and the abolition of cash bail. And these things can’t be looted.

The myth of the peaceable civil rights movement is also Elizabeth Hinton’s point of departure in America on Fire. The opening passage could have been plucked from a textbook: “On a cold Monday at the start of February, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr., and David Richmond sat down at a whites-only lunch counter at Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina.” The Greensboro sit-ins put the nation on the path to abolishing Jim Crow. Still, the integration of public amenities did little to alter discrimination in employment, schools, or housing; or to eliminate state and mob violence. Black youth did not abandon these demands, Hinton argues, though their tactics changed. Instead of organizing boycotts or registering voters, many took to “destroying property, assaulting police officers, and shooting in the direction of law enforcement, if not coming close to killing cops in self-defense.”

It’s in this space of hope, frustration, and escalation that America on Fire smolders. The first of two parts covers the years 1964 to 1972—the “crucible period”—in which “every major urban center in the country burned.” The book’s second half looks to latter-day rebellions in Miami (1980 and 1989), Los Angeles (1992), and Cincinnati (2001). Each chapter in Part I investigates a structural factor behind the rebellions: police expansion, public housing, white vigilantes, shootouts, criminal justice reform, schools, and commissions on “race relations.” None of these grievances existed in isolation: rather, policing bled into every aspect of what it meant to be Black and disposable in America. It was therefore not by accident that uprisings typically began with a routine police encounter: “Rebellion was a consequence of the all too predictable presence of the police,” Hinton observes.

Historians have seriously underestimated the number of urban rebellions, often repeating the official estimate of 150, given by the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (or Kerner Commission). Hinton has uncovered 1,951 distinct rebellions between 1968 and 1972 alone. (While Osterweil sees 1968 as a moment of retreat, most of the civil rights era’s uprisings came after this point.) Some of the most devastating violence took place in towns most Americans have never heard of: Waterloo, Iowa; Cairo, Illinois; Carver Ranches, Florida. America on Fire includes a timeline of every rebellion, its location and date. The timeline runs twenty-five pages.

It was smaller cities whose police departments benefitted most dramatically from the glut of federal money unleashed by Lyndon Johnson’s War on Crime, which formed the basis of Hinton’s first book. The federal government did not spend a dollar on local police in 1964. By 1970 it was funnelling $300 million into police departments. More police in low-income neighborhoods meant more chances for Black youth to be arrested, hurt, or killed. According to data compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, police killed nearly one hundred Black men under the age of 25 every year in this period. (Given the difficulty of documenting police killings, this figure is almost certainly an undercount.) Police killings were not “isolated events, unrelated to the expansion of police force in targeted Black neighborhoods.”

The targets of Black protest were neither senseless nor random. “Collective violence” followed a clear pattern: “Rebellion was always possible when ordinary life was policed.” After heavily patrolled streets, the main sites of rebellion were hostile schools and neglected public housing. In May 1969, violence broke out in Burlington, North Carolina after the high school cheer squad turned away four Black girls. In the ensuing rebellion, police killed a Black male student. The year before, public housing tenants in Bridgeport, Connecticut smashed up the housing authority office but left local businesses untouched. Wherever police deprived Black youth of rights, dignity, a decent living, or their lives, rebellion became inevitable.

The cycle of rebellion proved that liberal reforms were not working. More training and more technology did not fundamentally alter the role of police. “Instead of preventing crime and rebellion with armored cars and bulletproof vests,” today’s riot-prevention techniques involve “‘community-oriented’ and trust-building strategies,” alongside “Tasers and bodycams.” To permanently end the cycle of violence will require not reforms but “a different approach to public safety.” America on Fire is among the best cases against liberal reformism we have right now. It is not that “bad apples” ruin the batch. Rather, the rotten core of policing “could only spring from a poisoned tree.”

Why did urban rebellions largely disappear after 1972? For one thing, a whole generation had been either incarcerated or killed. “The systematic imprisonment of young black men,” Hinton writes, “removed from cities a significant portion of the young people who had committed and sustained the violence.” The decline of Black Power enabled youth gangs to fill the vacuum. These offered jobs, protection, and occasionally political power. Just days before L.A.’s 1992 rebellion, a group of Crips and Bloods signed a formal truce. The city’s homicide rate plummeted. “To be quite honest with you,” an LAPD Sergeant said, “we just don’t know why black gangs are not killing each other.”

By the mid-1990s, however, the power of the police was unimpeachable. “Black Americans,” Hinton argues, “more or less resigned themselves to the policing of everyday life.” The rebellions that did occur were more volatile. Anger and frustration curdled into something bitter, less legible politically. In the “crucible” years, protesters attacked the cops and looted mostly white-owned stores. Not so in later decades. In 1980, Black Miamians attacked two white men with bricks and a slab of concrete, and someone sliced off an ear. In L.A., young Black men beat a white truck-driver named Reginald Denny nearly to death. None of this violence invalidates the urgent need for transformative reform, then or now. Until then, “it is not a question of if another person of color will die at the hands of sworn, even well-trained officers.” It is not a question of “if another city will catch fire, but when.”

What made urban violence politically powerful? For Hinton, as for Osterweil, power concedes nothing without a rebellion. In 1968 and 1969, the city of Alexandria, Virginia witnessed two uprisings within the span of a year in response to systemic police violence. For three nights, Black youth volleyed Molotov cocktails through the windows of stores and government buildings. This finally convinced white city councillors to stop dragging their feet on police reform. But when the council rejected community members’ demands in favor of a community policing strategy, angry residents stormed out. Outside city hall they smashed up a light fixture and overturned some garbage cans. The cycle of violence continued.

America on Fire is replete with stories like this one. Rebellion forces city powerbrokers to the table. They agree to limited reforms, many of which do not actually make the Black working class safer. Hinton sees uprisings as a form of escalation from which local movements would not look back: once you’ve thrown a brick, it’s hard to believe in the ballot. Osterweil too, argues that rebellions transform individual political consciousness. Hinton argues that Cincinnati’s 2001 rebellion “anticipated a shift in Black protest” seen “in Ferguson and other cities later in the new century.” The main outcomes appear to be a settlement between the city and the ACLU, a “Community Problem-Oriented Policing” agreement, and a boycott of downtown estimated to have cost the city $10 million. In brilliantly capturing the cycle of police violence and urban rebellion, Hinton shows how often rebellion led back to the tactics of the nonviolent civil rights movement. From the boycott to the brick, and back again.

While Osterweil presents violent tactics as imperative for today’s activists, Hinton is somewhat harder to pin down. Despite arguing that the Civil Rights Movement’s power came from insurrection, Hinton commends today’s “militant, nonviolent protest.” Today’s organizers fuse “the direct-action tactics of the civil rights movement,” she notes, with Black Power’s “critiques of systemic racism.” Unlike In Defense of Looting, which appeared last summer, the timing of America on Fire means Hinton can address “the largest social movement in American history,” which marks the “return of rebellion.” Yet very few of these protests featured violence or property destruction: just five percent, according to the study she cites. This forces the question: is today’s movement the specter of 1968? Or are we living through a rupture, something vitally new

Together, In Defense of Looting and America on Fire should extinguish any remaining belief that collective violence is the abandonment of politics. By exploring the often-anonymous people who hurled bricks, pillaged stores, or shot back at the cops, Hinton and Osterweil provide new fuel for the history of social movements. “If looters are ‘not part of the protest,’” Osterweil asks, “then why do they appear again and again in liberatory uprisings?” In the present moment, we should ask the inverse: If looting is a clear path to freedom, why have so few recent liberatory uprisings included violence?

For Hinton, 2020 marked a triumphant “return of rebellion” driven by the mounting visibility of anti-Black violence. While the proliferation of camera-phones has made it easier than ever to document police violence, this is no truer today than when Black Lives Matter emerged in 2014. In addition to their scale, what makes recent protests distinct is activists’ almost total focus on nonviolent direct action. Between 2014 and 2017, Ferguson, Baltimore, Oakland, Salt Lake City, Milwaukee, Charlotte, and St. Louis all burned. The well of anger has not dried up. So why did 2020 look so different?

To understand this evolution, we should look to the periods in between high-profile police killings. The decentralized nature of the Movement for Black Lives has left local organizers free to experiment, as historians including Barbara Ransby and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor have expounded. After the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, many of us watched as local groups—often led by Black, queer, and trans youth—sprang into action. Demonstration flyers went up. Bail funds and pandemic mutual aid funds expanded. Wherever you lived in North America there was a group ready for this moment. Somehow, everyone knew what to do.

Today’s movement has largely transcended the sixties debate over nonviolence and self-defense. Activists today draw from an array of left-wing, anti-racist traditions that were never as opposed as some historians have believed. Out of the separate histories of the ballot, the bullet, and the brick, today’s activists espouse a politics we might call “all of the above.” Their repertoire includes direct action but also local electoral campaigns, the anarchist tradition of mutual aid, and targeted violence.

As Mariame Kaba has said, today’s movement knows “the importance of building a million different little experiments.” It is too early to tell whether this many-headed hydra will be more sustainable, harder for the state to contain. Until then, the history recovered by Osterweil and Hinton deserves to be understood and remembered—whether today’s activists choose to emulate it or not.

David Helps is a grad student in history at UMichigan. David Helps’s research and teaching focus on U.S. history since the 1960s, with an emphasis on policing, urban politics, migration, and political economy. His dissertation will cover the relationship between policing and multiculturalism in global Los Angeles between the 1970s and the Rodney King rebellion. He has written on the future of policing and economic justice in Detroit for the Cleveland Review of Books and Detroit Metro-Times.

If you liked this article, why not subscribe to Monthly Review, an Independent Socialist Magazine?

Spread the word