In 1919, a young lecturer at Columbia, Raymond Weaver, took on an unpromising task: assessing the merits of a forgotten 19th century writer. The writer’s novels, mostly set aboard ships, had been briefly popular, though not enough to sustain a long literary career, and they’d fallen out of print. Still, Weaver found surprising depth in the dusty tomes he was reading. You know, he thought, this Herman Melville fellow isn’t half-bad.

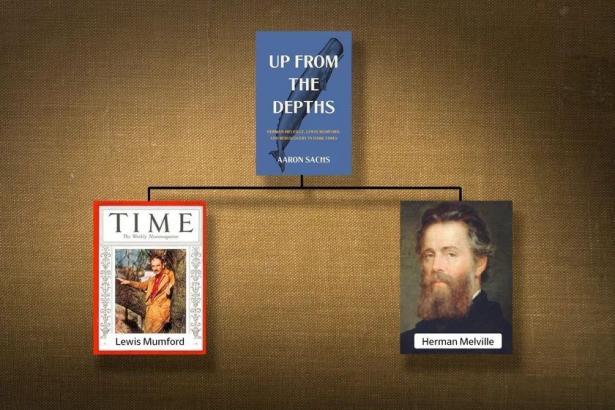

Not half bad at all. Melville’s writings were dark, bizarre, and rambling, but to a generation that had just suffered World War I, they pulsed with life. After Weaver raised the call, a Melville rush ensued. Virginia Woolf published a tribute. D. H. Lawrence declared Moby-Dick “one of the strangest and most wonderful books in the world.” And the critic Lewis Mumford, recognizing in Melville a kindred soul, wrote a biography.

If that last name—Lewis Mumford—means little to you, that’s understandable. Like Melville, Mumford was once a noted author, big enough to make the cover of Time. But also like Melville, he fell into obscurity, and most of his best books are out of print.

It’s a pity, as those books are agonizingly prescient. Modernity, Mumford complained at length, was too dependent on fossil fuels. New information technologies were rewiring our brains, leading to “broken time and broken attention.” And within liberal democracies lay fascist tendencies, he warned, waiting to burst out. These were idiosyncratic views when Mumford published them in the 1930s and 1940s. Now, not so much.

There’s something electrifying about encountering a long-dead author who somehow diagnoses your own predicament perfectly. It’s a feeling that the historian Aaron Sachs explores in his excellent new work, Up From the Depths: Herman Melville, Lewis Mumford, and Rediscovery in Dark Times. The book is a braided account of Melville and Mumford, aimed at exploring the strange resonance between their times and ours. It asks, with unusual directness: What’s the point of the past?

The conventional view is that we study history to avoid repeating mistakes. And while history surely provides a repository of instructive experience, that’s not all it offers. The past also gives us perspective. We frequently face the fish-can’t-see-water problem, in that many of the forces that shape our lives—gender roles, economic norms—are so pervasive that they’re hard to perceive. It helps to get another vantage, from a time when things were different.

That’s what Sachs finds in Melville and Mumford: clarifying perspective. Both sought to understand the “trauma of modernity,” Sachs writes, but they did so earlier, before it had fully taken root. Melville was so perceptive about white-collar psychology, as he was in “Bartleby the Scrivener,” because it wasn’t second nature to him but a new and troubling development. Mumford could appreciate the stultifying effects of mass entertainment because he remembered a time before movie theaters.

Melville is now a canonical author, widely admired for his farsighted reflections on capitalism, race, and the national character. By contrast, it’s possible to go through life a reasonably educated person and never hear Mumford’s name mentioned. Even still, Sachs notes, “your attitude toward ecology, modern architecture, and even social media has probably been shaped by Mumford’s eerily prescient writings.” Although he didn’t graduate college, a number of academic subfields—urban planning, the history of technology, environmental studies—regard Mumford as a key thinker. I’m hardly the only professor with a span of out-of-print Mumford titles on their shelf.

How Mumford became such a sharp critic of modernity is something of a mystery, as modernity was rarely so kind to anyone as it was to Lewis Mumford. In his prime, he was a respected intellectual who spent his days writing for the New Yorker, taking walks, making wild strawberry jam, and conducting brazen affairs with interesting women. (Mumford publicly praised contraceptives for facilitating “bi-lateral erotic relationships outside marriage.” His wife, Sophia, unpersuaded, joined two of his lovers in the “League Against War, Fascism, and Lewis Mumford.”)

Despite the sex and strawberries, Mumford maintained a bleak outlook, which tumbled out in a cascade of books from the 1920s through the 1980s. (Sachs rightly singles out the Renewal of Life quartet, published from 1934–51, as peak Mumford.) The new media of his day, which delighted his contemporaries, alarmed him. “The only place sacred from interruption is the private toilet,” he grumbled. The barrage of ads and propaganda not only penetrated our inner lives, Mumford believed; they numbed us, so that “we only half-see, half-feel, half-understand what is going on.” Eventually, he warned, our moral senses would erode and we’d become “passive barbarians,” prone to electing outrageous and cruel leaders. Decades before Donald Trump’s presidency, Mumford saw how information technology might deliver such an outcome.

What made Mumford interesting is that he took technology seriously. He believed that material innovations could transform our lives, if in surprising ways. His books are packed with short yet perceptive theses about the meaning of various technologies. The scientific revolution, for instance, he credited to advances in glassmaking. Not only were the instruments of science—telescopes, microscopes, beakers, air pumps—wrought of glass; the scientists themselves were part-glass cyborgs who used spectacles to keep reading into old age. Their quest for intersubjective truth—for getting outside their heads and seeing the world from other vantages—Mumford attributed to 16th century improvements in mirrors.

Or take sidewalks. It’s tempting to give little thought to them, to consider them—literally—pedestrian. But where others saw only concrete, Mumford saw a conspiracy. Before sidewalks, he noted, the street was an unruly arena where men on horseback jostled against blind beggars and workers carrying loads. Sidewalks accelerated traffic, but they also segregated it, allowing the rich to “roll along the axis of the grand avenue” while the poor trundled along on its edges. The street, once a shared space, became a “daily parade of the powerful.”

Some of Mumford’s most astute writing concerned fossil fuels. While others giddily watched cities rise and cheap goods flood consumers’ homes, Mumford never forgot the source of this abundance: the coal mine. Mining, which stripped the land bare and left a foul mess behind, was the “worst possible local base for a permanent civilization,” he felt. The problem wasn’t just its environmental toll but its psychological one, too. Unearthing buried stores of ancient energy, “mankind behaved like a drunken heir on a spree,” Mumford wrote. Fossil fuels taught us to ransack the environment, waste resources, and wave away thoughts of tomorrow.

Mumford laid out his case against coal in 1934, half a century before global warming became public knowledge. His foresight is impressive, but he was still groping in the dark. Someone writing today would be able tally the cost of fossil fuels with considerably more clarity.

They would also have a wider frame of reference. Mumford was born in the 19th century, so it is hardly surprising that he had blind spots. He cared about things like racism and colonialism, but mainly for what they revealed about the character of “Western man.” (“Wherever Western man went, slavery, land robbery, lawlessness, culture-wrecking, and the outright extermination of both wild beasts and tame men went with him.”) Mumford wrote about women—Emily Dickinson was a “spring flower” rising from the “sour soil” of her times—yet seemed uninterested in their distinct experiences. While his contemporaries joined social movements, Mumford spurned “dramatic political action” in favor of the “subtle reshaping of consciousness,” Sachs writes.

Still, for all his predictable shortcomings, Mumford audibly resonates. And what’s powerful about his writing isn’t that he puts things the way a 21st century author would. It’s that he doesn’t. He speaks the temporal equivalent of a foreign language, yet we can understand him perfectly. There’s something heartening in that. It suggests that we needn’t be historical orphans, frantically improvising responses to a cascade of destabilizing events. Rather, a tether of experience stretches out from the past, if only we can grab it.

Mumford searched for forebears and found Melville. The novelist’s dark sensibility and his sense that new material developments impinged profoundly on people’s inner lives rang true. Reading Melville’s “tragic explorations of his depths,” Mumford wrote, helped “unbare parts of my own life which I had never been ready to face.” Sachs feels that way about Mumford and Melville both, treating them as father and grandfather. Yes, climate change, COVID-19, and our other misfortunes seem unprecedented. But their “fundamental causes” aren’t, Sachs believes. And by watching Melville and Mumford think through previous incarnations of today’s woes, we can grasp the deep similarities that connect times.

Perceiving history’s “uncanny continuities,” as Sachs calls them, isn’t about learning lessons from the past so much as taking solace in it. In this vein, we read past authors as a sanity check. They reassure us that we’re not alone in what we see.

Up From the Depths: Herman Melville, Lewis Mumford, and Rediscovery in Dark Times

By Aaron Sachs. Princeton University Press.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Daniel Immerwahr is a professor of history at Northwestern University and the author of How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States.

Read Slate All Summer for Just $15

Save 50% on your first three months. Renews at $119/year.

Spread the word