Fight disinformation: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter and follow the news that matters.

In a 2019 article for Foreign Affairs, Yousef Munayyer declared the two-state solution dead. Munayyer, a Palestinian citizen of Israel who leads the Palestine/Israel Program at the Arab Center Washington, DC, wrote that the time had come to “consider the only alternative with any chance of delivering lasting peace: equal rights for Israelis and Palestinians in a single shared state.”

The next year, Peter Beinart, an Orthodox Jewish journalist who has moved left since editing the then-pro-Iraq War New Republic, made his own case for a single state. The articles, along with others like them, brought renewed attention to a similar proposal made by the late Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said in 1999.

A one-state solution would make all Palestinians and Israelis equal citizens of one nation that encompasses the land on both sides of what is called the Green Line, which refers to the borders established by Israel’s 1949 armistice with Arab nations.

During the 1967 war, Israel expanded beyond the Green Line by seizing, among other territory, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem. Those areas now include more than 5 million Palestinians who have been living under direct or indirect Israeli rule for more than 50 years. Unlike the roughly 1.6 million Palestinian citizens of Israel within the pre-1967 borders, Palestinians beyond the Green Line are not Israeli citizens and cannot vote in national elections. They are not afforded the rights given to the hundreds of thousands of Jewish settlers in the West Bank and East Jerusalem who, despite illegally occupying Palestinian land, are Israeli citizens.

Under a one-state solution, Israel would cease to be a Jewish state and would instead become like the United States and other nations that are not organized on ethno-religious grounds. Abandoning this commitment to Zionism remains anathema to a large majority of Israeli Jews and American Jews.

It would also be a major break from the longstanding push for a “two-state solution,” which would entail establishing a Palestinian state alongside the Jewish-majority state of Israel. Those who favor two states generally call for Palestine to be based in the West Bank and the much smaller Gaza Strip. (Israel withdrew from Gaza in 2005 but has effectively turned it into what critics call an “open-air prison” by maintaining almost complete control over who and what is allowed to come and go from the area.)

In practice, many Israeli and American proponents of a two-state solution have not been willing to accept a Palestine that has true sovereignty. Beyond that, Israel has spent decades building settlements and other infrastructure designed to effectively annex much of the West Bank and render the possibility of a coherent Palestinian nation impossible. Israel’s current far-right government has expanded settlement construction and has treated the West Bank as part of a “Judea and Samaria” that Jews have a right to control.

Munayyer argues that a one-state solution is necessary to provide dignity and democratic representation to multiple Palestinian populations: those who are citizens of Israel, those living under Israeli occupation in the West Bank, those under siege in Gaza, and Palestinian refugees denied the ability to return to where they once lived in Israel. The alternative, he says, is to continue with the “apartheid” system that many human rights groups have concluded Palestinians experience today.

When we spoke on Tuesday, Munayyer made clear that he did not see Israel-Palestine as an entity that would emerge overnight, or as a cure-all for resentments that have been building for more than a century. More immediately, Munayyer is calling for a ceasefire to prevent further suffering in Gaza, where more than 7,000 people have now been killed, according to the local health ministry, following the October 7 attack by Hamas that took the lives of more than 1,400 people in Israel.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You and others have written about how there is a “one-state reality” that already exists in Israel and Palestine. What does that mean? What does it look like for Palestinians?

We have heard a lot about Israelis and Palestinians and this idea of a two-state solution. These are things that we hear repeated over and over. It creates the idea that there are two sides and two parties and two countries that are in conflict with each other. It contributes to a failure to understand that the reality on the ground is one where there is only one state: That is the state of Israel, which controls the entirety of the territory, in one form or another, between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, in a land that was once known as Palestine—and today contains an Israeli state, which is recognized internationally by many people on part of that territory, as well as occupied Palestinian territory, which that Israeli state also controls. When we talk about a one-state reality, and this is a condition that has been in place effectively since 1967, this is what we are talking about.

And that means that there is ultimately one power that determines the vast majority of what takes place within this space, especially as it relates to political outcomes, the use of power, the monopoly of force, how resources are allocated, who has what rights, and who can go where and do what. That is the reality of millions of Palestinians and also Israelis. Of course, that state exerts far greater control over the lives of Palestinians than it does over Israelis.

Whether it’s one state or two states, what are the basic conditions that need to be met by any long-term resolution to the conflict?

Solutions are tools to address problems. When it comes to this issue there is a misunderstanding, particularly in the West, of what the problem is. The problem continues to be the fundamental denial of freedom and self-determination to Palestinians in their homeland. When you look at the situation, when you look at the map, when you look at the demographics, when you look at the realities on the ground, when you look at to whom rights are denied, you realize that this isn’t a two-state problem. This isn’t a problem that is solved by drawing some artificial line on paper. This is a problem that can only be solved by addressing the lack of those rights, which is not about separating people. It’s about affording them the rights that they’ve been denied by these systems.

Has this been an ideological evolution for you, or have you always supported a one-state solution?

As someone who is a Palestinian citizen of Israel, and someone who has been part of the American political experiment as well, I have felt that the two-state framework fails to address the rights and grievances of all of the Palestinian stakeholders that are involved in the Palestinian struggle for freedom. I also have a deep appreciation for the extent to which equality before the law, and political constructs that address people’s rights, are able to mitigate conflict and violence.

I have always been skeptical of partition being a solution to these things. But I think that over time, that’s become more and more clear to me. It should be clear that a one-state solution, or a two-state solution, is not going to turn this space into a utopia. We need to be honest about that. The question is what kind of system can be created that would most mitigate the conditions in which political violence grows. I think a two-state framework, especially the way that it is primarily discussed as what would be acceptable to Israel and the West, does not come close to addressing all of the issues. It would not be an outcome that reduces the conditions that create political violence, but probably one that only prolongs them.

Liberal Zionists have often suggested that if Israel had stuck to its pre-1967 borders and not embarked on the settlement-building that’s been going on for decades now, there could potentially now be a viable Palestinian state alongside Israel. You’ve called this “green-lined vision.” What do you mean by that?

First of all, there is this failure to see that there are rights denied outside of the occupied territory both to Palestinian citizens of Israel, who are fundamentally unequal within the Israeli system, and to Palestinian refugees, whose valid claims to land and life within the towns and villages from which they’ve been forced out exist in that space. I use green-lined vision to talk about that failure.

Part of what comes along with that is this ability to circumvent the real problem. People say, “Well, look, if you just don’t look at the West Bank and Gaza, Israel is not that bad.” I say to people, “Sure, if you don’t look at the extra 40 pounds around my waist, I’m a swimsuit model.”

You need to take reality as it is, not the way you imagine it to be. Israel has been occupying and controlling and entrenching itself within these territories for far longer than it hasn’t been. From 1949 to 1966 is a short period of Israel’s history compared to the remainder of it, which has largely been defined by this occupation. The green-lined vision allows people to ignore that reality.

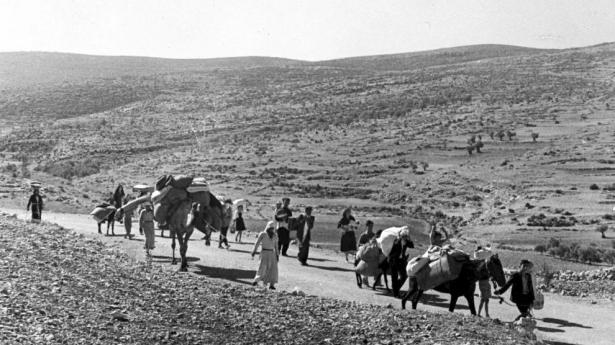

The other part is that it contributes to a romanticization of this period from 1949 to 1966. Many people, particularly liberal Zionists, imagine an Israel that was in its golden age. But for anyone who knows what that period meant for Palestinians—both in terms of the ones who were ethnically cleansed, the repression of Palestinian citizens of Israel under martial law inside Israel during that time, and numerous massacres that were committed in that period as well—we know that that’s not a period to romanticize. I talk about green-lined vision as a willing embrace of a series of myths that need to be busted for people to begin to grapple with the extent of the problem so that they can genuinely solve it.

In your conversation with New York magazine’s Eric Levitz, he pointed to polling showing that one-state with equal rights for Jews and Palestinians is not particularly popular with Palestinians. The same poll showed that Palestinian and Israeli support for two-states was not particularly high, either. How do you see current Palestinian attitudes toward a one-state solution?

What Israelis and Palestinians are saying is they want to be free of each other. It’s not necessarily because it’s impossible for them to imagine living with each other. It’s because their experiences of being in contact with each other have been experiences of conflict. The question is: Is there a way of creating conditions in which their experiences cannot be those of conflict? I think that is possible. If that idea can be nurtured and promoted—and moved in the direction of actual policy—public opinion changes. Public opinion is far more movable than billions upon billions of dollars of settlements that are entrenched in the West Bank, and billions and billions of dollars that have been entrenched in the infrastructure of apartheid across the entirety of the country.

The vast majority of people in the West Bank and Gaza have never known a day of freedom. They’ve never known an interaction with Israelis that has not been one of military occupation or apartheid. When you ask them about whether or not they want to live in one state with Israelis, you have to understand that their entire experience has been shaped through the prism of their lived reality. That produces a lot of these trends.

For more liberal and secular Zionists, a key part of the importance of a Jewish state is the idea that it provides a place where Jews can be safe from persecution. How do you address the concerns Jews have about being oppressed in a single state in which they are in the minority?

I would say that Palestinians have every reason to be as equally concerned for their safety in such a space. Palestinian history with Israelis has not exactly been one where they have been shown tenderness and love and kindness. Again, when we think about what a process like this could actually look like, it’s not going to happen with a flip of a switch where one day all the Jews in the land wake up and suddenly they’re governed by a completely different regime that’s made up of Palestinians and they don’t know what’s going to happen to them. That boils down to a fear-mongering that prevents any reasonable thinking about how to move from one place to the next, and has left us stuck in this reality that just gets increasingly uglier.

More immediately, what do you think needs to happen in relation to Gaza?

We need an immediate ceasefire. This is the biggest no-brainer in the history of no-brainers. You’ve got thousands of people who’ve been killed. Thousands of more who probably will be killed. This is not making anybody safer. It is contributing to more deaths, more insecurity, more fear, more hatred. There’s no justification for it. There are so many in Gaza right now who are being killed for nothing other than just being alive in Gaza. That has to come to an immediate end.

What do you think President Biden and his administration should be doing that they have not been doing?

I think that their message has been devastatingly poor. They need to immediately call for a ceasefire. Immediately. They are saying, “Well, look, Israel has a right to defend itself.” First, the people who are being killed, including some 2,000 kids at the moment that we’re speaking, are not the people who carried out the attack on Israel on October 7.

The kids who are the lone survivors of families of 18 or 19 people who are being buried in mass graves, do you think those kids are going to think well of the military that killed their families? Do you think they’re going to be any more inclined to see Israelis in a peaceful way? Or Americans for that matter? We are sowing the seeds of resistance for generations to come by supporting this kind of insanity.

If there was a military solution to this, Israel, statistically, would have stumbled upon it by mistake, given all the different bombardments of Gaza in the past. But all that we’ve seen is an increase in the capabilities of Hamas in Gaza, and no less support among Palestinians for armed resistance against Israel.

In his Oval Office address last week, President Biden framed the need to send tens of billions of dollars in military aid to Israel and Ukraine as part of a broader effort to defend democracy. Is Israel a democracy?

The messaging from the Biden administration has been—it’s hard to even find the words to describe this. It’s as if it’s been designed to insult the feelings and intelligence of everybody in the region outside the Israelis. This is not about democracies coming under attack. The Israelis run a military occupation and an apartheid regime. Half the Israeli public was up in arms over the direction that its government was going to undermine the rights that they had as Israeli Jews, and you have Joe Biden talking about democracies coming under attack. For people in the Third World who hear this, it sounds like it’s coming from another planet. It does incredible damage to American credibility, and it makes it that much harder for American diplomacy to be successful all over the world.

At some point, this is going to end. Afterward, I believe, we are going to be in a deeper one-state reality than we’ve ever been. The Israelis are going to be less and less inclined to ever relinquish control of territory. They are going to leave Gaza in a state of complete devastation and disarray. Palestinian politics is going to continue to be a mess, as well as Israeli politics. At the same time, the risks of failing to address this issue in a comprehensive and lasting way have never been higher. That is the morning after this. We have a choice to make about where we go from there.

Noah Lanard: I’m a reporter at Mother Jones where I’ve covered immigration since 2017. Before Mother Jones, I was a fellow at Washingtonian. I got started in journalism while freelancing from Mexico City for The Guardian, Splinter, and Vice. I’m based in New York. Email me at nlanard gmail or message me on Twitter at nlanard.

Mother Jones is a reader-supported investigative news organization honored as Magazine of the Year by our peers in the industry. Our nonprofit newsroom goes deep on the biggest stories of the moment, from politics and criminal and racial justice to education, climate change, and food/agriculture.

We reach 8 million people each month via our website, social media, videos, email newsletters, and print magazine. Our fellowship program is one of the premier training grounds for emerging investigative storytellers.

Founded in 1976, Mother Jones is America’s longest-established investigative news organization. We are based in San Francisco and have bureaus in Washington, DC, and New York.

We are independent (no corporate owners) and are accountable only to you, our readers. Our mission is to deliver hard-hitting reporting that inspires change and combats “alternative facts.”

THANK YOU, MOTHER JONES READERS!

We just finished off our fall fundraising drive, and we were able to raise about $225,000 over three weeks to help make the reporting you get from Mother Jones possible. Thank you so much to everyone who pitched in! And thanks to everyone who didn't or simply can't, because Mother Jones wouldn't exist without people who read and share and care about our journalism.

It's unfathomably hard keeping a newsroom afloat these days, and we're grateful to have a community of readers whose donations make up about 75 percent of our funding. A broad base of community support is the only reason we're still standing. It's what allows us to do the type of journalism you turn to Mother Jones for in the first place: deep dives, big investigations, prioritizing and sticking with underreported beats, and bringing a fiery and fact-based voice that adds context to the day's news.

Unfortunately, that $225,000 haul means that we did come up about $28,000 short of our fall fundraising goal. That's rough, because we have zero wiggle room in our budget, and given how tough it is in the news business right now, we can't afford to fall behind like what happened last year—when we had to find $1 million to somehow cut, and still came up a bit short on the whole.

So even though we won't be doing another big fundraising push until December, we absolutely need to see a great many of you continue to pitch in and help make our reporting that doesn't follow the pack, and that is desperately needed right now, possible.

Bottom line: To raise the money it takes to keep Mother Jones charging hard, we need this specific ask at the bottom of each and every article to bring in more donations than it typically has. And you care enough about our work to be reading this: If you can right now, please pitch in before moving on to whatever it is you're about to do next and think “maybe I'll get to it later.” We need your support now, we need your support day-in, day-out, not just when we're in the middle of a big fundraising push like we just finished.

Donate to Mother Jones, Support nonprofit, independent journalism. Subscribe to Mother Jones.

Spread the word