The long stagnation that began in the mid- to late 1970s and continues to the present day is evidenced by a long-term secular decline in the growth rate of output, the growth rate of new investment, and capacity utilization. This stagnation has been one with a half-century of real wage flattening for nonsupervisory workers and a dramatic increase in the wealth holdings of the upper classes and managerial elites.1

Associated with this stagnation has been an increasing concentration of firms across a whole panoply of industrial and financial settings. In addition to numerous manufacturing industries, we might list: oil, banking, food production, distribution and retailing, legacy airlines, credit cards, high-tech services (inclusive of search engines and computer facilities), music delivery, phone services, and internet retailing.2 This increasing concentration has solidified monopoly power across the economy and, in accordance with the tendency of monopoly power to slow down investment growth, helps explain the general slowdown of growth over the last fifty years.3

It is the purpose of this article to relate how this creeping stagnation has added its own force in contributing to the monopoly power associated with consolidation and to current wealth disparities. The argument runs along two lines. The first concerns how the imperative for corporate growth channels monies into mergers when the prospects for new investment slow up. The second (and related aspect) concerns the generation of corporate monies in excess of new investment (termed free cash) that, together with debt, funds mergers. Free cash results from federal deficits derivable in large part from: (1) tax rate reductions on the rich and (2) efforts to counter stagnation and episodes of financial unraveling. Free cash funds mergers and acquisitions, but has not been limited to such.4 Free cash has acted as flow collateral for the expansion of corporate debt to provide mega-funds for spillage into equity markets. In addition to mergers, this spillage consists of expanded dividends and stock buybacks. Amounting to trillions of dollars, this disgorging of cash has been a major force for expanding the wealth positions of the rich.

The Growth Imperative

Capitalism is a growth system. The imperative for growth is part of the cellular makeup of corporate life. Remuneration for corporate executives is tied to success, which is measured through profits and growth. Higher profits generate higher stock values and foster a tighter bond between investors and management. When internal prospects for new investment are apparent, corporate managers pursue expansion through new investment, ecologically mislabeled “green” investment. When such prospects start to diminish, or when surplus funds are available, managers look horizontally toward acquiring other firms through merger.

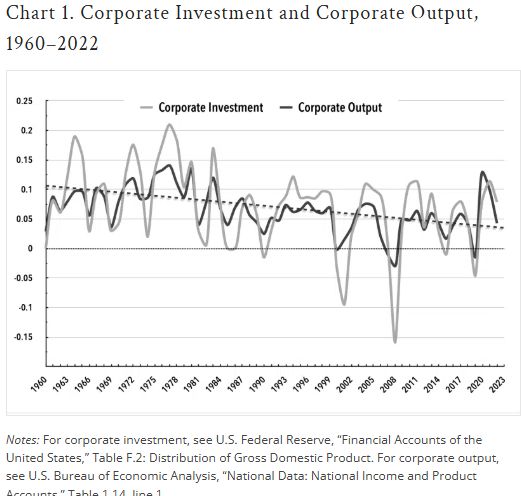

Historically, merger waves have been tied to booms as booms generated sufficient profits for outward expansion.5 In contrast to earlier merger activity, however, the ongoing merger consolidations of late have had as their backdrop a long period of creeping stagnation. Chart 1 shows the secularly falling rates of corporate output and new investment since the mid- to late 1970s. As the data show, in any three- to seven-year period, there might well be a significant increase in the rates of growth relative to what was immediately apparent before. In consequence, long-term secular stagnation is hard to detect for people living under its mantle, particularly for those in the upper classes, as the ongoing stagnation has not been marked by any diminution of profits—quite the contrary. The rise of globalized production with supply chains tied to low-wage labor depots, the virtual disappearance of significant union power, the rise of the gig worker and layering of seniority, and the productivity advances associated with the displacement of labor by computerized machinery all made for a rise in gross corporate profits relative to labor compensation and output. In addition, the continual decline in corporate taxes and the “free cash” generated through government and private deficits (more on this later) generated large amounts of funds for merger activity.

Mergers and Relative Valuation

In the pursuit of corporate growth, there are but two options: new investments or mergers. In terms of the corporate growth imperative, the value of what John Maynard Keynes called “old investments” (existing firms that could be purchased on equity markets) expands in relative valuation when the prospects of new investment peter out.6

A simple numerical example illustrates the point: A firm ascertains that its best investment prospect over a given time horizon is to install new investment of $100 million, which prospectively would generate $10 million dollars in additional profit. As a result, the new investment’s rate of return would be 10 percent over the time period considered. Let us assume that in addition to this new investment, the firm considers the acquisition of a “target” firm, which would prospectively add an additional $20 million dollars in profit over the same time horizon. Gauged by its own internal rate of return on new investment, the target firm would, in relative valuation, be worth $200 million. If the prospective internal rate of return shrunk to 5 percent on the $100 million dollars of new investment so as to garner only $5 million in profit, the target firm’s relative valuation would double to $400 million. Different firms, of course, will have different profit prospects for new investment, so the relative valuation of any particular target will vary across firms. But if the profit prospects on new investment shrink across the economy, aggregate merger activity will tend to rise relative to new investment.

Unlike profit rates on total capital, the trend in prospective profit rates on new investment and the extent of investment opportunities can only be inferred. The decline in the rate of corporate investment is evidence of a long-term decline in these opportunities. Under such conditions, we should expect a rise in merger activity relative to new investment.

Relative valuation is also tied to the distribution of income between capital and labor. New investment is undertaken for essentially two reasons: (1) to increase revenues through the expansion of facilities for the production of new and existing products and services, and/or (2) to increase efficiencies through the reduction of input costs through labor or material savings. If we make the provisional assumption that the additional profits attributable to new investments are proportional to output, or to a proportional expansion of output over a given time period, then it follows that when the distribution of income favors capital, the relative valuation of existing capital expands.7 This is because less of the total profits, expressed as a fraction of the total profits, is attributable to the new investment. Or, expressed somewhat differently, more of the total profits, expressed as a fraction of the total profits, is attributable to existing vintages of capital. As mergers represent the purchase of existing capital, merger activity will expand along with capital’s share.8

Of course, such simplifications omit as much as they include. Time horizons for various vintages of capital differ enormously, as do the time horizons for various firms’ growth and decay. Profit gains attributable to new investment are not always proportionate to output or expansion. But the essential point is that, in general, stagnant growth and a rise in capital’s share will tend to expand the relative valuation of existing capital installations and enhance the forces for consolidation.

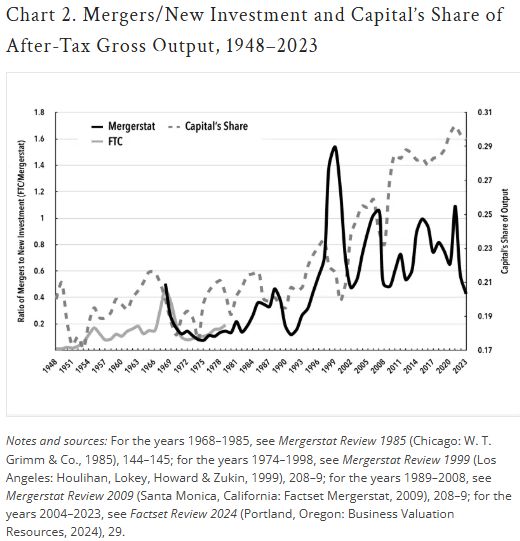

We see evidence for this in Chart 2, where the merger/new investment ratio rises along with capital’s after-tax gross share of corporate output. The graph portrays the two merger series that are readily available to the public: the Federal Trade Commission’s “Large Merger Series,” which is confined to manufacturing from 1948 to 1979, and the Mergerstat Review series, which compiles publicly announced merger offers and divestitures.9 The latter represents all dollar expenditures on mergers and acquisitions on announced transactions reporting a purchase price. Though numerous mergers do not report a purchase price, the bigger ones typically do. Accordingly, the series should be understood as an underreported proxy variable.

Although the upward trend of the merger/new investment ratio is quite distinct, the year-to-year variations are highly volatile. The average merger/new investment ratios of late, however, have been quite high. From 1995 to 2023, the dollars devoted to merger activity were 75 percent of new investment. Absent divestitures, merger dollars comprised 56 percent of new investment.

Free Cash, Government Deficits, and the Decline of Tax Rates on the Rich

The rise of capital’s share of corporate output and the corresponding rise of the merger/new investment ratio (shown in Chart 2) has occurred with a rise in the ratio of corporate gross profit after tax to new investment. This rise reflects the generation of increasing amounts of “free cash,” which has financed some part of merger activity. Free cash derives from the additional purchasing power added by government and noncorporate deficits (noncorporate investment in excess of noncorporate savings), with the former being the primary factor in the generation of this additional purchasing power.10 Since the 1980s, federal deficits have become quasi-permanent. As government deficits are the alternative to taxes, such deficits have as their mirror image a decline in the relative use of taxes to fund government expenditures, and a rise in free cash.

The decline in the relative use of taxes is dependent on two factors: the amount of income being taxed and the applicable tax rates. In recent years, the magnitude of personal federal taxes on high-income earners has expanded both absolutely and relative to the underlying population.11 This expansion seems quite anomalous given the notorious decline in tax rates levied on high incomes. Nominal marginal tax rates for high-income households hovering around 90 percent were left over from the Second World War. These high rates continued into the 1960s but in time fell into the 70 percent range. During the so-called Reagan revolution, marginal tax rates fell dramatically—first to 50 percent and then again to 28 percent. They eventually rose into the high 30 percent range. Given a variety of loopholes, “effective” tax rates were considerably lower. Nevertheless, they too fell in line with nominal rates.12 Given these tax rate declines, the expansion of taxes taken from the rich gives us a sense of the decided split in the income distribution favoring the wealthy and high-income receivers.

The main decrease on taxes affecting high-income earners took the indirect route of a massive decline in corporate taxes, both in corporate tax rates and in the percentage of total federal receipts. The high corporate tax rates of the Second World War were apportioned in accordance with the “excess profits” accruing to corporations as a result of the war. The “excess profits” tax went into abeyance at the end of the Second World War but was refurbished when the Korean War commenced. When the excess profits tax expired at the end of 1953, the highest marginal corporate tax rate came in at a bit above 50 percent and corporate taxes furnished 29 percent of federal receipts. In a series of steps, corporate rates declined to 35 percent by 1993 and held steady until 2018, when a 21 percent tax went into effect. In addition, various government subventions, such as investment tax credits and liberalized depreciation allowances, significantly reduced actual taxes beneath the lowered nominal rates.13 The total contribution of corporate taxes to federal expenditures is now less than 10 percent.14

Although payroll taxes on workers have increased dramatically over time, it has been increasingly difficult to raise income taxes on workers —particularly on nonsupervisory workers—for, as noted, the real wages of this group of workers have been close to flat for half a century. Unwilling to raise tax rates on the rich and unable to raise sufficient taxes on workers, Congress has allowed government deficits to become the quasi-permanent default option. Corresponding, free cash has become quasi-permanent as well. As free cash is the leftover cash after funding new investment, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the largest part of funding for corporate mergers and acquisitions is an outcome of federal deficits, with noncorporate deficits adding a supporting role.

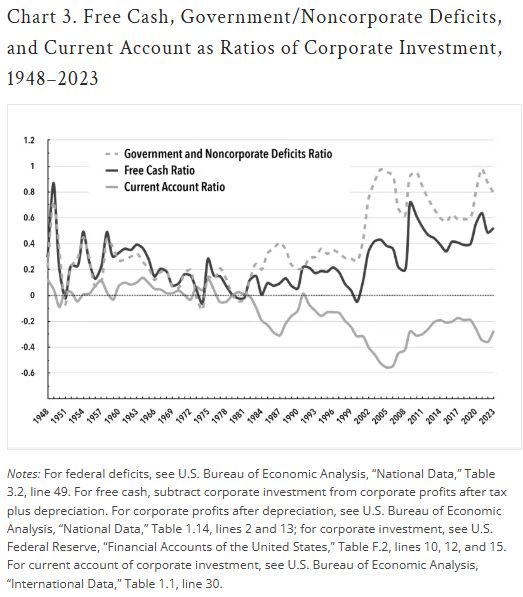

Chart 3 displays the expanded purchasing power of government and non-corporate deficits in relation to the free cash generated. All series are expressed as ratios of new corporate investment. The difference between the two series is reflected in the negative current account—the difference between exports and imports together with net remittances of capital between U.S. firms and residents and their foreign counterparts.15

Free Cash and Capital Spillage

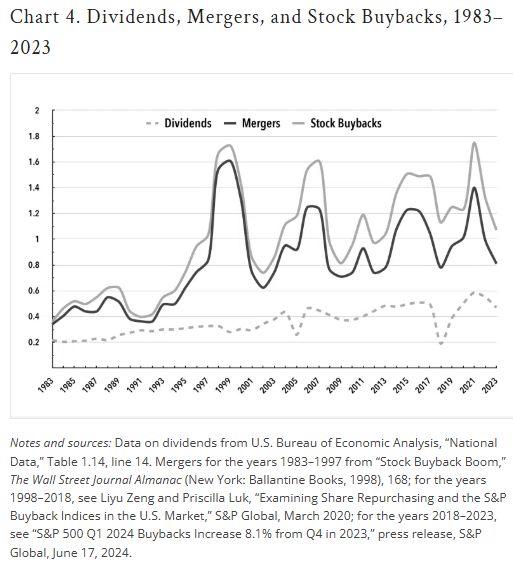

Given the large amounts of free cash, one might surmise that the corporate world would be debt-free, or at least debt-light. This is not the case. Corporate debt has been growing along with free cash.16 Free cash provides flow collateral and reassures bond buyers that new debt can be serviced and paid back. These additional debt funds permit corporate managers to utilize cash over and above the free cash generated. Apart from the possibility of being parked in cash holdings, free cash and the additional funds derived from debts are spilled into the capital markets through three main channels: dividends, mergers, and stock buybacks. All three of these options prop up the stock market and, as a side benefit, the compensation packages of top managers where stock options and grants provide a large part of their remuneration. Dividends provide additional funds to institutions and households that invest in stock. One suspects that a large portion of these dividends are plowed back. In acquiring target firms through mergers, acquirers jack up the stock price of targets through acquisition premiums (the rise in the stock prices of acquired firms), which in the last few decades have approximated 40 percent.17 Stock buybacks buy out stockholders who feel that the offered price is what the stock is worth. Those who abstain will only part with the stock at a higher price. Accordingly, and within limits, the stock price will rise.18

In providing flow collateral, free cash is the intermediate term between the safest debt available—the treasury bonds making up the deficits that generate the free cash—and the far riskier layers of corporate debt supported by the free cash. The irony of this debt layering is that the larger the federal deficits, the greater the amount of free cash generated, and the higher the level of corporate debt and risk. In that the mega-piles of free cash and debt-generated funds find their way into the stock market, the wealthy benefit directly by federal deficits. In that the federal deficits have arisen largely as a result of tax rate declines on the rich, these equity gains through capital spillage can be considered derivative gains from tax rate reductions.

Chart 4 displays the result of including all three channels of cash spillage into the stock market (dividends, mergers, and stock buybacks), each expressed as a fraction of corporate investment. From the late 1990s, this spillage averaged over 80 percent and often exceeded the monies poured into new investment. This aggregate spillage reflects the movement away from an economy based on production to an economy based on finance and the enhancement of financial wealth. It should be noted that this estimate of spillage is a conservative estimate in reference to both mergers and stock buybacks. As mentioned above, the Mergerstat Review does not record the numerous mergers whose prices are not announced. The stock buyback series is the Standard & Poor’s tabulation (to my knowledge the only one available) and is confined to firms on the S&P 500 list.

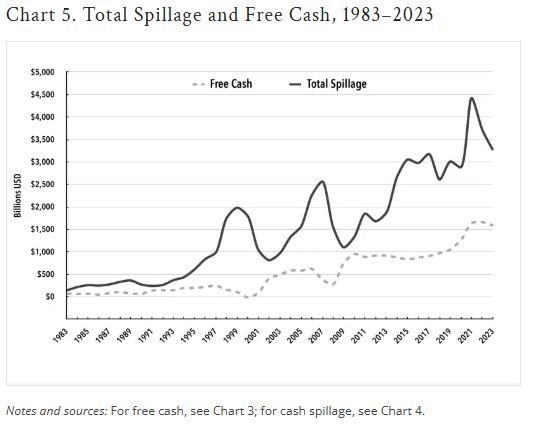

The expanded role of corporate debt in the spillage can be captured by comparing free cash aggregates to the spillage displayed in Chart 4. Chart 5 shows this comparison. Notice the large discrepancy between total free cash and the spillage of dividends, mergers, and stock buybacks per year. This discrepancy—now over one and one-half trillion dollars—is covered by corporate debt. As mergers and stock buybacks represent stock taken off of stock exchanges, Chart 5 partially captures the net trading of debt for equity—a risky proposition at best, but one that finance scholars have often championed in reference to financial efficiency. Interest on debt can be subtracted from gross returns to lower taxes, whereas dividends cannot. Moreover, mergers allow acquirers—at least those with large amounts of free cash and the ability to borrow more—to finance startups and firms with prospective new investment projects.19 This so-called efficiency of debt finance, of course, comes at the expense of an increasing risk of financial fallout.

A Brief Note on Governmental Responses to Stagnation and Recent Financial Unraveling

According to a standard textbook, federal deficits are necessarily incurred during economic downturns when tax proceeds fall along with economic output. To balance the budget during downturns would require that government spending fall along with private economic activity. Such “sound finance” would assuredly make the downturns worse. As a historical example, we can look at the lead-up to the downturn of 1937–1938. In the attempt to balance the budget by cutting back on deficit spending, the Roosevelt administration interrupted the recovery from the depths of the Great Depression. With an about-face on deficit concerns, recovery was resumed. Then the Second World War came. Along with a massive expansion of government spending, with corresponding tax hikes on all levels of the population, massive deficits were incurred to further the war effort. The instantaneous recovery from the Depression made for an associative connection of prosperity, high government spending, and deficits.

In light of recent decades of long-term stagnation, the ongoing deficits of late might be understood as the required remedy. Combined with a lowering of interest rates by the Federal Reserve to counter falling rates of investment, the combined remedial actions appear in line with standard prescriptions. In accordance with the views of high policy officials, the fallout of repeated financial debacles in 1987, 1991, 2001, and the mega-debacle of 2008–2010 solidified the case for definitive action along orthodox lines.20 The fallout surrounding the pandemic only reinforced previous policy choices. Recent deficits attained historic highs and interest rates historic lows.

However orthodox, these fiscal and monetary actions were carried out against a backdrop of increasing monopoly power. Evidence for this expansion of monopoly power derives not just from concentration ratios within industries but by increasing margins of price over marginal cost. In one study, Jan De Loecker and Jan Eeckhout found that markups were relatively steady from 1950 to 1980, with prices averaging approximately 18 percent above marginal cost, but then rose to 67 percent by 2014.21 Against such an industrial and financial setting, the expanded stimulus offered up by federal deficits and cheap money bumped up against increasingly powerful restrictionist tendencies. Instead of a rapid expansion of real investment, deficits and cheap money generated large amounts of free cash and increased debt loads. Near-free money encouraged more plowback into new high-risk ventures and more margin buying of stocks. These outcomes were, at least in part, consciously pursued. Through quantitative easing the Fed purchased trillions of dollars of long-term treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities so as to lower long-term interest rates. Absent any significant jump in new investment, the business press and others found solace in the expansion of stock values. Such expansion was understood as providing a “wealth” effect that would stimulate consumer confidence and spending.

This too was in accordance with received theory. The ruling theory of asset prices is that prospective future returns underpinning the assets are discounted back to the present to arrive at their current value. Accordingly, a lower interest rate (discount rate) will drive up present values. Of course, this theory presupposes some type of clairvoyance as to future returns. As to the “wealth” effect of stocks having any substantial effect on the economy, one cannot understate the case. The wealthy own an inordinate percentage of existing financial assets, and we can—exceptions apart—confidently assume that their level of consumption would simply remain at the high level of their station.22

Increased deficits and low interest rates were put in place in the service of stabilizing the economy. No doubt these deficits and lower interest rates saved the system from some of the worst possible economic scenarios, particularly those that surrounded the Great Recession of 2008–2010 and the pandemic. But ever-expanding deficits and cheap money were forty years in the making. The continued long-term trend of creeping stagnation suggests that their efficacy in countering slow growth was (and is now) quite limited. Yet, deficits and cheap money did (and will) expand the forces for free cash generation, the centralization of capital through mergers, and funds for cash spillage, making the rich still richer.

Notes

- ↩ For real wages of nonsupervisory workers, see White House, 2024 Economic Report of the President, March 2024, 448, Table B-30; White House, 2021 Economic Report of the President, January 2021, 494, Table B-30.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster, Robert W. McChesney, and R. Jamil Jonna compiled manufacturing data from 1947 through 2007 on a host of industries in which the top four firms in the industry accounted for at least 50 percent of shipment value. Partly for reclassification reasons, the number of industries characterized by such concentration multiplied around four times. See John Bellamy Foster, Robert W. McChesney, and R. Jamil Jonna, “Monopoly and Competition in Twenty-First Century Capitalism,” Monthly Review 62, no. 11 (April 2011): 1–39.

- ↩ The association of monopoly power and investment slowdown has had a long history dating back to the early twentieth-century in the writings of J. A. Hobson and Thorstein Veblen. In the post-Second World War period, Joseph Steindl, Paul A. Baran, and Paul M. Sweezy refurbished the thesis in the face of a prosperous period. In the view of the authors, the question of “Why depression?” was answered in large part by the monopolistic character of a modern economy. Baran and Sweezy’s answer to “Why growth?” was answered by epoch-making inventions, wars, and their aftermath: a synthetic culture of consumerism and the expansion of finance. Elaborations on the oligopoly stagnation theme have been carried out by other authors over decades in Monthly Review.

- ↩ Free cash monies are the difference between corporate gross profits (profits after tax plus depreciation) and new investment. Depreciation is a real thing. But for a business contemplating expansion, depreciation is a “bookkeeping” cost—that is, money that does not leave the firm. Accordingly, a dollar charged to depreciation cannot be distinguished from a dollar of after-tax profits.

- ↩ Up until the recent expansion of mergers dating from the 1980s, there were three major waves. The first dates from around 1895 to 1904. Now termed the “Giant Merger Wave,” it witnessed the fact that “more than half of the consolidations absorbed over 40 percent of their industries and nearly a third absorbed in excess of 70 percent” (Naomi R. Lamoreaux, The Great Merger Movement in American Business, 1895–1904 , 2). Paradoxically, the wave was at least partly caused by the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890. The U.S. court system largely followed British case law, whereby “monopoly” had a specific meaning that referred to separate firms conspiring against the public in support of price maintenance. Mergers were sufficiently infrequent so as to escape the case law. As a consequence, investment bankers, like J. P. Morgan, saw mergers as a loophole bypassing case law as it pertained to monopoly. The second wave in the 1920s was also superimposed on a decade-long boom. It saw second-tier firms consolidate into bigger firms, challenging the dominant firms left over from the Giant Merger Wave. The U.S. Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission allowed these (mainly) horizontal mergers to proceed on the dubious contention that these new consolidations would bring more competition to earlier monopolistic formations. Oligopolies were the result, with monopoly pricing now being enhanced by an enlarged sales effort characterized by product differentiation, advertisements, and service arrangements. In the 1960s boom, mergers largely took a conglomerate form, whereby large firms jumped from their primary industry to enter into other industries. Government authorities again stood on the sidelines as these corporate outreaches “deconcentrated” individual industries even as overall concentration expanded.

- ↩ John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (London, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1953 [originally published 1936]), 151.

- ↩ For the proportionality assumption of investment in reference to output, I follow Evsey Domar, Essays in the Theory of Economic Growth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1957), chapters 4 and 5. For the proportionality assumption in reference to efficiencies, I follow Joan Robinson, “The Production Function and the Theory of Capital,” Review of Economic Studies 21, no. 2 (1953–1954): 81–106.

- ↩ For an extended mathematical treatment, see Craig Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality (London: Routledge, 2018), 60–63. The following is a simplified version. Let C be the prospective gross profits that the firm will garner with new investment added over a given time horizon and Z the projected profits without the new investment. So, C – Z is the projected additional profits due to the new investment. If these gains are proportional to output (Y) or to a proportional expansion thereof, we can write C – Z = hY. As C will be the gross profit attributable to the existing capital stock (K) plus the new investment (I), the relative valuation of the total capital stock (K + I) to the new investment (I) will therefore be C / (C – Z) or (K + I) / I = C / hY. Simplifying, we obtain K / I = 1 / h * (C / Y) – 1. So, when capital’s share of output expands, the value of the older capital expands relative to new investment.

- ↩ The Federal Trade Commission series is contained in Statistical Report on Mergers and Acquisitions (Washington, DC: Bureau of Economics, November 1977). Since its inception, the Mergerstat Review has been produced by a number of companies. It is now entitled the Factset Review and is published by Business Valuation Resources, Portland, Oregon.

- ↩ In recent years, noncorporate investment has generally been in excess of noncorporate savings, particularly in the period leading up to the housing blowup of the 2008–2010 debacle, when housing investment greatly exceeded personal savings. For a variety of years, however, the balance has registered relatively small surpluses. See John Bellamy Foster, R. Jamil Jonna, and Brett Clark, “The Contagion of Capital,” Monthly Review 72, no. 8 (January 2021): 1–19. For a detailed mathematical treatment in constructing free cash estimates, see Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, chapter 2, chapter 6, 87–90.

- ↩ The share of federal tax liabilities for the top quintile of income receivers rose from 55 percent in 1979 to over 80 percent in 2020; the share of the top 1 percent more than doubled, from 14 percent to 31 percent (Tax Policy Center, Historical Shares of Federal Tax Liabilities for All Households, 1979–2020 [Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2024]).

- ↩ Various loopholes, such as the exemption of interest on state and local bonds and a lower capital gains tax, have significantly reduced taxes from the high nominal rates sketched out here. (For “effective tax rates” on high-income earners, see White House, 2017 Economic Report of the President, January 2017, 176, Figure 3-9.)

- ↩ Allowing firms to write off more capital expenditures faster (that is, allowing firms to expand depreciation) transfers more of what used to be called profit into the “cost” category.

- ↩ S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “National Data: National Income and Product Accounts,” Table 3.2: Federal Government Current Receipts and Expenditures.

- ↩ Imports in excess of exports suck money (and purchasing power) out of the country. Negative net flows through net remittances do the same thing, while positive remittances bring additional purchasing power to the United States. In recent years, these remittance payments and receipts have favored the United States (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “National Data,” Table 4.1: Foreign Transactions in the National Income and Product Accounts, lines 9 and 24).

- ↩ See Foster, Jonna, and Clark, “The Contagion of Capital,” 12, Chart 4.

- ↩ Mergerstat Review 1999: Premiums Offered, 1974–1998 (Los Angeles: Houlihan, Lokey, Howard, and Zukin, 1999), 208–9; Mergerstat Review 2009: Premiums Offered, 1984–2008 (Santa Monica, California: Factset Mergerstat, 2009); Factset Review: Premiums Offered, 2014–2023 (Portland, Oregon: Business Valuation Resources, 2023), 44.

- ↩ By disgorging cash to buy back stock, the firm is worth less in terms of real assets.

- ↩ For an introduction to these alleged benefits of leveraged mergers, see Michael C. Jensen, “Takeovers: Their Causes and Consequences,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 2, no. 1 (Winter 1988): 21–48.

- ↩ Among other accounts prior to the pandemic fallout, see Ben S. Bernanke, The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and Its Aftermath (London: W. W. Norton and Co., 2015); Henry M Paulson Jr., On the Brink (New York: Business Plus Publishers, 2013); Alan Greenspan, The Map and the Territory: Risk, Human Nature and the Future of Forecasting (New York: Penguin, 2013).

- ↩ Jan De Loecker and Jan Eeckhout, “The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications,” NBER Working Paper No. 23687, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts, August 2017.

- ↩ Not so for the underlying population. The “wealth” effect associated with housing in the late 1990s through 2007 ended in disaster.

Craig Allan Medlen is Professor Emeritus of Economics at Menlo College, in California. He graduated with a B.A. in Economics from University of California Berkeley in 1966 and received his Ph.D from U.C. Santa Barbara in 1973. His most recent book is The Failure of Markets: Energy, Housing and Health (2022).

Dear Reader, Monthly Review made this and other articles available for free online to serve those unable to afford or access the print edition of Monthly Review. If you read the magazine online and can afford a print subscription, we hope you will consider purchasing one. Please visit the MR store for subscription options. Thank you very much. — Monthly Review Eds.

Spread the word