The UE NEWS asked retired UE Political Action Director Chris Townsend to write a summary of how UE’s membership base has changed over the years. Brother Townsend joined the UE staff in the late 1980s, when the membership was primarily (though not exclusively) manufacturing workers, and retired in 2013, after the union’s membership had expanded to include significant numbers of public-sector, higher education, federal contract and rail crew workers, and supplemented his own experience with detailed research from UE convention proceedings and interviews with participants.

The ongoing organizational renewal and substantial growth of the United Electrical Workers (UE) is one of the most distinctly remarkable stories in the U.S. labor movement in decades. Few other unions have suffered such losses from state repression, raiding attacks by opportunist unions, and the catastrophic effects of corporate job relocation — and survived. Of the original 42 unions who comprised the founding roster of the Congress of Industrial Unions (CIO) in 1938, a grand total of eight survive intact today. UE is one of them. The remainder have passed out of existence, been destroyed by repression and employer attacks, or been merged into larger unions and lost forever.

Born in the electrical, radio, machine tool, and related manufacturing industries, UE membership for the first four decades remained nearly completely within those industries. The constant emphasis on the need to organize the unorganized did lead to many thousands of non-manufacturing members being brought into the union, but virtually all were clerical or technical workers already working side by side with UE’s members for the same employer. Occasional small groups of non-manufacturing workers would find their way to UE and try to join. They were dutifully encouraged to unionize but directed to another union, whichever union that might already represent that sort of worker elsewhere. Union “jurisdictions” were a serious business then, with most unions dutifully staying in their own lane so far as the types of workers they organized. With UE’s organizing base in several specific manufacturing sectors, it was almost unimaginable that unrelated types of workers would somehow make a home in a union dominated totally by factory workers.

Along Comes Antioch College

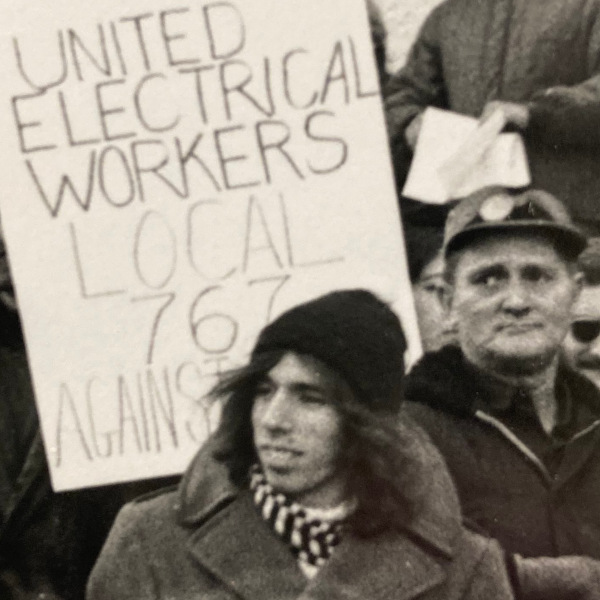

Members of UE Local 767 protest the Vietnam War in 1971.

By the mid-1960’s, during the beginnings of the student organizing upsurges across the country in support of the civil rights movement and in opposition to the burgeoning Vietnam war, Antioch College student Larry Rubin contacted UE asking the union to organize the service and maintenance workers at the Yellow Springs, Ohio, campus. Rubin and other students had already told the workers about UE’s record at the bargaining table, its democratic processes, and its rank-and-file character. The reflexive impulse of the union was to refer them to another union, a union better suited for their type of work. But Rubin, the students, and the workers involved all made the case over and over that UE was the union they wanted to belong to.

UE organizer Mel Womack, one of the early African-American staff members, finally went to bat for bringing the Antioch workers into UE, taking Rubin’s plea all the way to the UE officers in New York City. “I knew about UE from my family in Philadelphia, and this was the right union for these workers. But we had to convince them that it would be a good fit,” commented Rubin.

Making the decision a bit easier for the union was the fact that virtually the entire union membership in Ohio had been destroyed or lost during the preceding 15 years of raids and plant closings. As the union organized new factories and reclaimed some lost shops in the heavily industrialized state, the Antioch College workforce offered a chance to rebuild a solid foundation for new manufacturing organizing. A 1965 strike for union recognition was quickly won by the college workers and students, and their official entry into UE allowed for the reconstitution of UE District Seven shortly after.

For the past 60 years the Antioch members have played a consistent and positive role in the life of the union that had nearly turned them away. But the members of UE Local 767 today comprise just a handful because of the closing of most Antioch operations in 2008 — a victim of epic mismanagement. The Antioch College story transcends the entire era from when UE began to seriously consider new non-manufacturing workers for membership, and it also teaches the lesson that in an economy driven completely by profits and “efficiency,” even a workplace such as Antioch is not immune to layoffs or closing.

Tough Decisions

By the 1970’s, UE began to experience wave after wave of layoffs and plant closings as manufacturing bosses began their exodus from the U.S. for low-wage zones across the globe. Retired UE Director of Organization Ed Bruno commented that, “All through the 70’s and into the 1980’s we suffered major losses as plants closed. Formerly big plants were whittled down to just a few hundred members or even less. It was hard to imagine. By the time Reagan was elected President the floodgates opened. We had tried to organize runaway plants in the South, with only limited success. And those plants were not immune to closing either, as we discovered with the loss of the Tampa Westinghouse and Charleston General Electric plants we had organized. No plant was safe anymore.”

As the 1980’s ground on, the union experimented with a number of strategies to organize again and regain lost membership. “By 1987 and ’88 we were forced to rethink our relationship as a union to the manufacturing sector. We looked at trying to organize semiconductors, medical equipment, service shops and other industries still largely based here in the U.S. And we decided to take a look at the plastics industry.” said Bruno. “We went all-in.”

The Plastics Organizing Effort

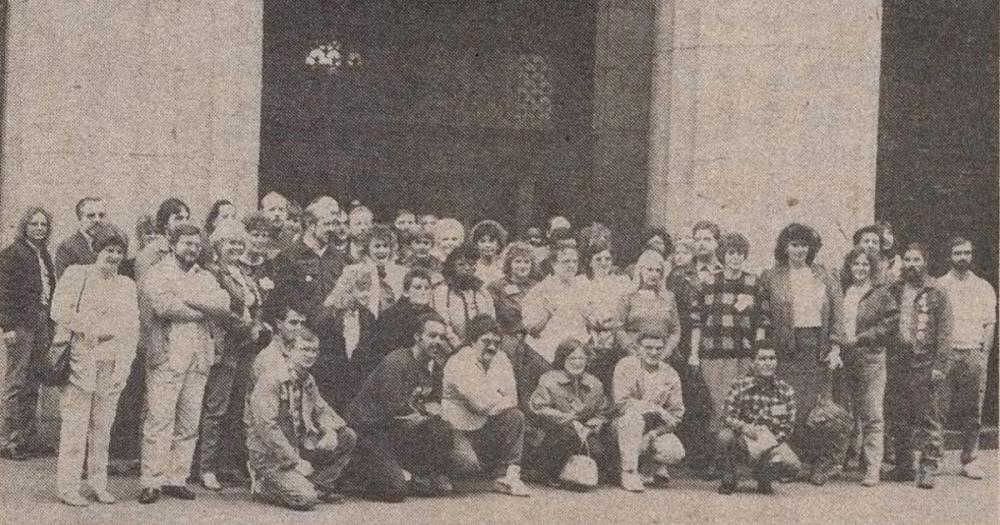

Plastics workers from across the country gather at the UE national office in Pittsburgh, November 1989.

The plastics industry presented a formidable target for UE organizing. It was decentralized and largely unorganized. Profits were high, and wages were low. Early probing into the 600,000-worker sector yielded above-average interest in unionizing by many workers, but employer resistance was fierce. Sensing the need to move quickly under the deteriorating conditions, UE devised the “Plastic Worker Organizing Committee” (PWOC) plan of action, where several hundred plants would be approached by the union simultaneously. All with the hope of triggering a contagious wave of new organizing spirit among the workers in the industry as was the model of legendary U.S. organizer William Z. Foster in his approach to organizing meatpacking and steel industries early in the 1900’s.

- For more history on the PWOC efforts see the thumbnail history here by the Emergency Workers Organizing Committee. And for readers interested in Foster’s legacy his collected works, American Trade Unionism, is available from International Publishers.

Early PWOC results were encouraging, as large numbers of workers responded to UE’s outreach and call for organization, better wages, better benefits and working conditions. Plastic product and component manufacturing plants were leafleted widely and workers were contacted in several hundred plants. PWOC groups were started across a dozen states and the union launched a full mobilization with hundreds of union staff, local leaders, members, and UE supporters deployed. But almost immediately employers responded to the organizing push with fanatic and illegal repression.

Workers were fired, threatened, and terrorized from coast to coast. Union-busting meetings were held in union targeted shops, and so pathological was boss resistance that plastics employers not even encountering UE yet forced their workers to attend anti-union meetings. In UE’s historic base city of Erie, Pennsylvania, then and now the home of many thousands of UE members and retirees from several locals, the plastics employers held meetings to coordinate their plan to repulse the organizing effort by all means legal and illegal. Gigantic billboards were put up across the city decrying UE’s organizing effort, all to induce fear and panic among the several thousand workers in the Erie PWOC area.

Crushed

Only a handful of plastics shops were organized by the end of the nearly two-year effort. One, Reid Valve in Leetsdale, Pennsylvania, was organized only as a result of the massive lawbreaking by the company during the organizing drive. Current UE International Representative John Thompson, then a shop leader, led the drive in the plant where the employer engaged in illegal firings and conduct so severe that the NLRB ordered recognition for the union without an election as the remedy for the outrageous company lawbreaking. The exceedingly rare “bargaining order” granted to UE by the labor board for the Reid workers may well have been the only such order granted that year to a labor union trying to organize.

Organizing progress across the entire union had nearly come to a halt as the union-busting cloud descended on workplaces across all sectors. Between the late 1980’s and 1992, the union was able to win elections and organizing drives totaling barely several hundred workers per year. This crisis was mirrored across the entire labor movement, as mass layoffs, partial closings, and complete plant shutdowns accelerated. The inability to crack into the plastics industry in spite of the herculean effort by the entire union was sobering. Was there a future for UE? Or any union? Was there a way forward? Could the union even hang on, let alone revive?

New Course Needed

The question of widely diversifying the industrial sectors being organized by UE remained a larger option, and by the early 1990’s a small trickle of such shops had already been won. Experimentation with organizing non-manufacturing workplaces and affiliating existing independent unions took form, but were small in scale as most efforts remained focused on factory organizing. Bus operators in Greenfield, Massachusetts joined city and school district workers already part of UE. Movie theatre and radio station staff had organized into UE in Boston. Construction workers in Sacramento, California signed up. A temporary employment agency was organized in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Radio station staff were won in Los Angeles, California. Bank safe installers and alarm technicians were organized in Philadelphia. A newspaper staff unit had been organized in Vermont. And there were others, mostly small shops. Recruiting union members in already-organized open shops also brought in some needed new blood as the union implemented a renewed push in this regard as well.

Early Forward Momentum

With the election of Bob Kingsley as the new Director of Organization in late 1992, it was apparent that UE was in immediate need of expanded experimentation with the organization of new sectors. “We didn’t want to give up on organizing manufacturing workers, but we had to do something to bring in new members to offset the losses,” said Kingsley. “Our factory members stepped-up and saw the need too. Over and over and over again we relied on them to take the UE message to workers far away from the factory floor.” Magnifying the earlier work of Ed Bruno, Kingsley launched a major outreach to independent unions across the country. Results were significant, and in 1993 alone more new workers were organized either by affiliation votes or NLRB elections than in the previous decade. Public sector workers, truck drivers and mechanics, port workers, warehouse workers, and food service workers joined, boosting the numbers of non-manufacturing members in UE dramatically. Factory workers continued to be organized as well, a welcomed uptick after years of decline.

Iowa

The campaign to win the affiliation of the large Iowa United Professionals (IUP) independent union was key to opening the door to additional units not traditional for the union. This large statewide unit of state professional workers had voted in a leadership vote to join UE in 1989, only to be counseled to return home and develop actual rank-and-file support for the move. By the spring of 1993, both IUP and UE were ready, and the overwhelming vote to join UE by the membership was another shot in the arm for UE’s rebuilding efforts. Kingsley recalls, “We won the Iowa affiliation vote in the middle of their epic spring flood, where half the state was under water. We had UE factory members from all across the country crisscrossing the state, extolling the UE’s merits from the shop floor perspective, in the midst of this calamity. We got votes for determination alone and won overwhelmingly.”

The big Iowa win allowed UE to launch additional organizing campaigns for unorganized public-sector workers at school districts and county workplaces, with new successes. By 1995, graduate teaching and research assistants at the University of Iowa contacted UE, and veteran organizer Carol Lambiase was tasked with determining if a campaign was feasible for the 2,600 workers.

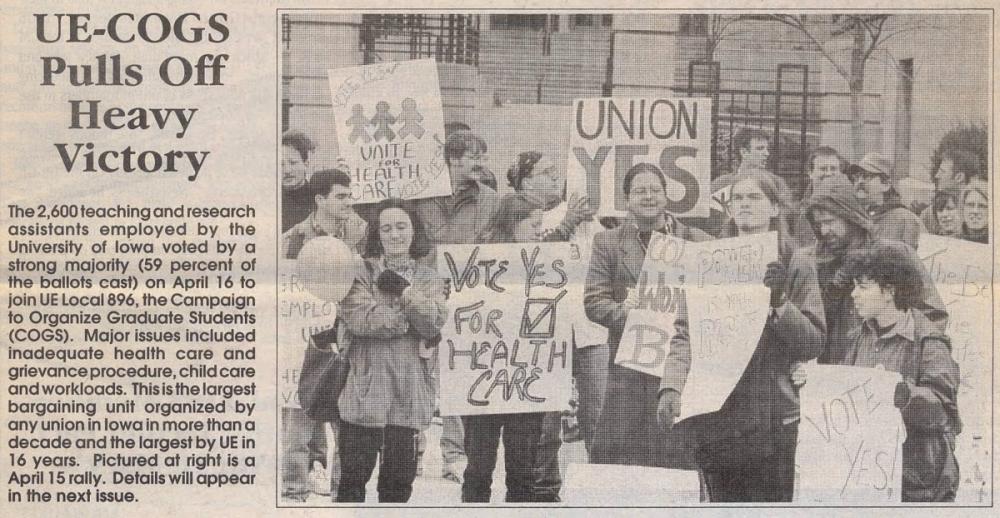

After an enormous and sustained campaign, the University of Iowa workers voted overwhelmingly to join UE in April of 1996. This marked the largest organizing win in several decades for UE and gave the union new energy to expand organizing even further. Everyone in UE was celebrating the big Iowa win, but a common question was, “Tell me again what kind of work they do?”

UE NEWS coverage of the election win at the University of Iowa.

New Directions

The organizing success in Iowa, including UE’s very first graduate worker unit, all set the stage for continued UE growth in the public sector as well as other new sectors. Through the 1990’s and beyond, UE set down additional membership roots in the health care sector, at food coops, among rail crew van drivers, and among federal contract workers, all while maintaining a realistic focus on new organizing in the original manufacturing sector. Gene Elk and Mark Meinster followed Kingsley as directors of organization in the last decade, and each led membership and staff in the direction of further growth in a diversity of sectors. Both helped set the stage for the explosive growth of the last three years, enabling the union to emerge from the pandemic period strengthened with more than 35,000 new members joining from higher education ranks alone.

A Remarkable Renewal

The role played by UE Local 896, the Campaign to Organize Graduate Students (COGS) — the University of Iowa graduate teaching and research assistants and first UE win in that sector — was trailblazing. Local 896 has compiled a solid record of rank-and-file and democratic local functioning, aggressive struggle on behalf of the members’ interests, and in opposition to the blizzard of political attacks waged against public employees in Iowa for almost 30 years. This outstanding record is all the more remarkable given that owing to the nature of their profession, workers do not remain for lifetime careers. Each successive generation must relearn the union history and from the point they are hired must join the front ranks of the local.

It would have been inconceivable for any of us who spent time in UE — in my case a 25-year career — to have imagined that Local 896 would have helped to rekindle UE to such an awesome extent. But why not? When those of us who were grappling with the difficult and at times unsolvable puzzle of just how we were going to reverse UE’s decline, and build new membership again, we always believed that there existed a large section of workers who wanted real, aggressive, militant, and member-run unionism. We learned that workers are shaped somewhat by the work they perform for a boss someplace, but more than that working people are shaped by a desire not just for any union, but for a better kind of union. UE’s assembly line workers, machinists, toolmakers, and factory hands are now largely replaced with higher education, public service, health care, rail, retail, and technical workers. But rank-and-file unionism pushes on to another generation, delivering real results and proving that member-run unionism works.

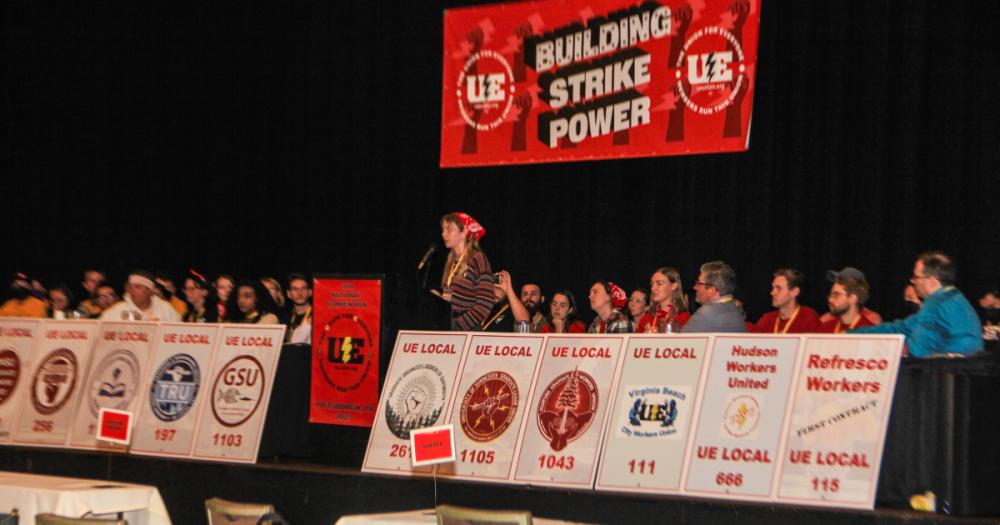

A full stage during the Organizing Report at the 2023 UE Convention.

UE holds high that banner, and the response of workers like the several tens of thousands who have poured in to the union’s ranks in the past several years is proof of that. A special union salute is in order to the UE founders, the old-timers who kept UE going in the most trying of times, the current membership, officers, local activists, and staff who kept rallying to UE’s banner, and now to the many new faces arriving to replenish the ranks.

If UE did not exist it would have to be invented. On to the next stage of growth, and wherever that takes us.

Subscribe!

If you like what you read, please consider subscribing to the UE NEWS — for as little as $5/year you can support great labor journalism and receive the print edition of the UE NEWS four times per year.

You can also sign up to receive monthly UE NEWS Bulletins via email, or follow UE on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Spread the word