It's official: The New York Times says we're having "a Teachout moment," by which the paper's editorial board means it's time for Gov. Andrew Cuomo to stop trying to knock progressive challenger Zephyr Teachout off the ballot and to debate her instead. It's a play on "teachable moment," and it makes you wonder what's intended to be taught.

Does the paper believe Cuomo should be taught a political lesson in the wake of the Moreland Commission scandal, after a scorching Times report revealed he's being investigated for meddling in and protecting allies from the anti-corruption probe? Or does the Times think that Cuomo should learn that he can afford to play nice, for a moment, and give state voters an opportunity to examine his four years in office, alongside a barely known rival with an odd name who declares that he's been "a failure as a Democrat"?

Teachout's run is as much a challenge to the fatalistic, anti-electoral politics left as to Cuomo. The Fordham Law professor says progressives shouldn't merely complain about the corporate takeover of the Democratic Party; they should fight for its soul. Since working as Internet communications director for Gov. Howard Dean's 2004 presidential run, she's been an evangelist to a broad range of insurgencies, from the early Tea Party (very different than it is today) through Occupy Wall Street to North Carolina's Moral Mondays, on the lookout for new populist energy that can be channeled into a challenge to corporate power - and to the Democratic Party's Cuomo wing.

Teachout herself comes from the party's Cuomo wing - as in Mario Cuomo, the governor's father. A believer in FDR liberalism, she says, she loved Mario Cuomo, but thinks his son is the symbol of a party that lost its way. An electoral politics novice, as a candidate anyway, she famously challenged Cuomo for the Working Families Party nomination in May, a sign that the progressive party, independent from but usually allied with Democrats, was fed up with a governor who was great on social issues like gun control and gay marriage but bad on economic ones. Cuomo has blocked tax hikes for the rich, cut the estate tax and enacted other tax cuts and exemptions for both businesses and individuals. Until recently, he opposed letting cities raise the local minimum wage.

But a last-minute deal between the governor and the left-wing party, brokered by Mayor Bill de Blasio, wound up with Cuomo supporting a roster of WFP demands, including a plan to force "independent" state Senate Democrats to stop caucusing with Republicans and rejoin their party, public financing of elections and a plan to increase the state minimum wage while also letting cities hike theirs by 30 percent. The last-minute deal meant Teachout lost the WFP nomination - and decided to challenge Cuomo anyway in the Democratic primary.

Then came the Times' blockbuster report on Cuomo's meddling with the Moreland Commission, which he appointed to investigate state government corruption, then disbanded halfway through its planned 18-month term. A three-month Times investigation "found that the governor's office deeply compromised the panel's work, objecting whenever the commission focused on groups with ties to Mr. Cuomo or on issues that might reflect poorly on him."

Cuomo's response to earlier charges that he'd interfered with the commission investigation had been to say, "It's my commission. My subpoena power, my Moreland Commission. I can appoint it, I can disband it. I appoint you, I can un-appoint you tomorrow . So, interference? It's my commission. I can't `interfere' with it, because it is mine. It is controlled by me." He more or less stuck with that defense in his belated reaction to the Times story. That satisfied neither the Times nor Cuomo's progressive critics.

Last Wednesday Lawrence Lessig sent out a massive fundraising appeal for Teachout's campaign, the only non-congressional race that his Mayday PAC, established to get money out of politics, will endorse in. Lessig calls Teachout " the most important anti-corruption candidate in any race in America today." On Cuomo's Moreland defense, Lessig is slashing.

That was Nixon's argument when he told the Watergate special prosecutor to withdraw his demand for the tapes that eventually brought down his administration. It was wrong then. It is wrong now. It shows a stunning blindness to the role of a leader - certainly a self-proclaimed leader of the anti-corruption cause.

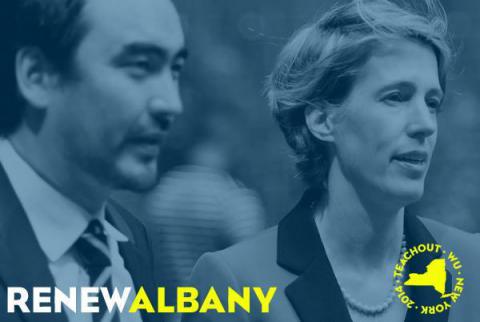

Still, Teachout and her lieutenant governor running mate Tim Wu, the Columbia law and former Federal Trade Commission official who gave us the term "net neutrality," remain long shots in the September primary. Although former boss Howard Dean appeared at a fundraiser with Teachout last Tuesday night, he declined to officially endorse her. (The Dean-inspired group Democracy for New York City is still considering the question.) Teachout says she wasn't disappointed.

"We're not running an endorsement-focused campaign," she tells me, although she happily announces she was just endorsed by comedian-activist Lizz Winstead. "We got the Lady Parts Justice endorsement, I feel really good about that!" Her strategy is to focus on high-information voters who vote in New York's low-turnout Democratic primaries. Although recent polls find Cuomo barely touched by the Moreland scandal, she sees hope in a Siena survey that found more than half of voters believe the governor makes decisions on what's best for him politically, not what's best for New Yorkers. "This has the potential to be the upset of the century," she insists, pointing to stunning losses by Virginia Rep. Eric Cantor and Hawaii Gov. Neil Abercrombie, who were likewise accused of putting political ambition before serving their constituents.

In our conversation in her tiny midtown Manhattan office last week, Teachout was alternately feisty, funny, wonky - and clearly planning to run for something else if her long-shot bid for governor fails. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

I just got an appeal from Lawrence Lessig raising money for you, in which he compares Andrew Cuomo to Richard Nixon when it comes to the Moreland Commission scandal - in the way that the governor insisted that since it's "his" commission, there's nothing wrong with him having a hand in what it does.

So what's your question?

Well, would you compare him to Nixon?

I understand why people make comparisons like that, but my focus is very much on - and I'm not just saying this - on what I see as the power of the governor of New York, which is larger than the power of the governor in any state. My focus is really on what the Founding Fathers worried about at the Constitutional Convention, which is how, when you have too much centralized power, it leads to corrupting the entire process, and then the characters involved. In New York, as you know, the governor's budgetary power and the power over commissions is outsized.

Decentralized power isn't just good for democracy: It's smart, you learn better. Andrew Cuomo has become the master of collecting as much power as possible to himself. And that has made him forget the basics of law, which are - forget the particular legal questions: the idea that the same law applies to all of us. That's what we saw in his saying, "It's my commission, it's mine, it's mine, it's mine!" It's a misunderstanding of the fundamental equality in the idea of law. It's also bad politics, which is why you see half of people polled now saying he's serving himself, he's not serving the public.

We last talked a few weeks before the Working Families convention, before you'd even declared as a candidate. Were you surprised by the role Mayor de Blasio played in whipping support for the governor there?

I was. I was fairly confident going in that I would get the nomination. I think everybody was surprised by the last-minute deal, even the players in it.

What specifically about it?

I now understand that Andrew Cuomo never took my candidacy that seriously. He's had to learn time and again that I'm quite serious. I think some of the players were surprised I ran. Then I heard that there was more of a chance the WFP would come to a deal, and I was surprised. But I realized there was no real impact on me - I wasn't a part of the deal. I briefly considered whether or not I should join it.

Why didn't you?

Well, nobody from the governor's office ever reached out to me, so I was never really asked. That may be because I made clear that I wouldn't even consider a deal that didn't address public education funding. We're below constitutional levels of funding in this state. There are a whole bunch of areas the deal didn't address. Fracking is another. But I'm very proud of my role in that deal: It's pretty clear that Andrew Cuomo would never have committed to bringing back the IDC [the Independent Democratic Conference that caucuses with Republicans to support GOP leadership]. If I'd dropped out, there would have been no IDC deal. So it's a very big lesson in the importance of even the shortest of primaries - even a three-day primary!

That's a really good point. So often progressives are asked to cave in - whether to drop a primary challenge, or drop negotiating demands in legislation - before they can even use their leverage at all.

Yeah, it's just a basic lesson: Don't leave power on the table. Don't give it away. But there's things that are very clearly not in the deal. There's nothing for education in the deal. It doesn't touch tax policy - the tax code of the state is the moral code of the state, and right now it's upside down. We have a Reaganite governor on this. Maybe there isn't the organized constituency on tax policy that there is on other issues, but to me that's fundamental. It's a failure of democratic governance.

So speaking of education: You promise to back public schools over charter schools, and I wonder why you think charter schools have emerged as such a divisive issue for Democrats, with so-called Wall Street, or Cuomo Democrats on one side, and progressives on the other. When I interviewed the mayor about his role in the WFP convention, I talked about the ways that the governor really went out of his way to break his wings - particularly that rally he held in Albany with Eva Moskowitz to protest the mayor's really tiny move restricting new charters.

I think it's a fundamental assault on the public itself .

On the concept of a public sphere?

There's all kinds of assaults on the concept of a public sphere, to use your language, or the concept of a "public" that includes all of us. To take on public education is to take on the public at its heart.

Well, they would argue that charter schools can still be public schools - yes, there are charter chains that are private, but others participate in the public system.

Yeah, but in the larger sense. Ever since 2008 we've had this assault on public education, with a lot of different faces. This week's face is Campbell Brown - by the way, I've challenged her to a debate on Twitter, I haven't yet heard back to her.

Oh, OK, I'll get that out there.

These are many faces of a similar assault on public education. You have to wonder whether there's a race component to it too, with the changing demographics in the country. The idea that there would be schools in which you do worksheets and don't have art - that's the Common Core part of it. That's not the kind of school your kids are going to, that's what those *other kids are going to. Kids need art and music and phys ed at school. They're as fundamental as any math worksheet; in fact, they enable the math worksheet. So the assault on public education is coming from all these different places.

The charter controversy, there's some comfort that politicians take in the charter movement. Many parents who are leaders in their own communities put their kids in charters. They choose it because they have the opportunity and that's what's best for their kids. But then they're held up as the front people for this privatization - when in fact they're just trying to do what's best for their kids, and if we had good public schools they wouldn't go to charters in the first place. It's an easier thing to stand behind charters than some other forms of privatization, but it's the same thing, as far as I'm concerned.

How do you think we wound up here. I mean, Andrew Cuomo is such an easy symbol.

If he's so easy, why is this campaign so damn hard? (laughs)

Well, one answer is that it might be easier if you had done more local political stuff - but I'm not saying that you should have become a machine Democrat in your youth and waited your turn!

But really what I was asking was, look at the difference between Mario Cuomo and Andrew Cuomo: How did we get here, as Democrats? To go from the man who was the symbol of liberalism and the challenge to Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, symbolically and rhetorically as well as practically in policy terms. Someone who protected and projected FDR liberalism.

Yes, exactly. I love FDR liberalism. I love Mario Cuomo. So in the early '90s, many Democrats gave up on the Democratic project, the fundamental issue of caring for those less well off. Mario Cuomo was a leader in early childhood intervention for children with disabilities, for example, and now Andrew Cuomo is dismantling the systems that Mario Cuomo built. Parents of kids with disabilities have seen that their projects are getting centralized, privatized and dismantled by Andrew Cuomo. More broadly, Democrats have given up on the project of caring for the worst off, as well as building a powerful middle class. Oh, and the whole idea of anti-trust.

Democrats had a choice. Instead of recognizing that a small-business economy is the heart of a thriving democracy, many Democrats gave up on the anti-trust project itself. So we have this really important idea that has almost no good public language anymore, the notion that power concentrated in the hands of too few is bad in the private realm as well as the public. I think this is a missing piece in the Democratic Party ethos - the importance of taking on concentrated private power. We are now living under a system where we are seeing the dangers of that. Dangers that FDR understood; Thomas Jefferson wanted an anti-monopoly clause in the Constitution. The founders knew feudalism is dangerous to democracy.

But if you say to a crowd, "Down with monopolies," they look at you - they don't understand what you mean. But "down with monopolies" was a populist idea in the 1880s, this idea that we had to protect our economy from the Comcasts, the JPMorgan Chases, the Monsantos . we don't really have the language anymore.

We developed it for banks: the language of "too big to fail" became very useful.

Exactly! Elizabeth Warren also talks about it in terms of the game being rigged. So one of the things that Tim and I would do is use the powers of anti-trust that the state has.

Progressives were very excited about Warren's win, and about Mayor de Blasio's as well. Did his intervention on behalf of Cuomo make you question his genuine populism - or do you just think, hey, this is politics, we'll live to fight another day and be on the same side again?

Oh absolutely, hey, this is New York politics! I'm not the only one who imagines how much easier de Blasio's job will be when he has a governor who shares his populist progressive values.

I actually think it's an extraordinary time to be in politics. See, there's this thing that happened in 2008: the crash. And a lot of politicians went on as if nothing had changed. I started talking to Stan Greenberg, the pollster, because we needed polling about money in politics, around the time of Occupy. And he said, "The most surprising thing in this poll is, OK, yes, people want to change the role of money in politics. But the big thing is, people want to break up the big banks!" I said, what about people who want to break up the big companies? And he laughed and he said, "Are we asking for that?" And the fact is, we're not! We're struggling with a new political vocabulary to describe the situation that we're in.

I remember a piece you wrote in the Nation about the Tea Party, when it first emerged in 2009 - about the need for progressives to pay attention to the populist element in it. And I tried to do that, I went to the first Tea Party rally in San Francisco, and I wrote about this woman who was trying to enlist Tea Party support for banking regulation, breaking up the banks. They were polite to her, they didn't throw her out - but there wasn't much interest. And of course, we know how it turned into an anti-Obama movement and really began to represent that traditional Republican base. But I appreciated that at the start, you tried to see across left/right boundaries.

Well, we had a group I co-founded, A New Way Forward, and we sent people to Tea Party rallies, to talk to them. The Tea Party went through various stages, and once it went into the anti-healthcare stage, it was taken over by big money. Certainly some people were motivated by xenophobia; and certainly other people were motivated by a sense that they're out of power, and they're looking for somebody to tell them why they're out of power. Then it got very racialized.

And then we had Occupy, and I know you did a lot of outreach to Occupy, too. What do you think about what I would call the failure of Occupy to deliberately channel activism into the Democratic Party?

I obviously think you should never leave power on the table. Electoral politics are central to any exercise of power. It doesn't mean it's the only method. I've also been to Moral Mondays in North Carolina. So much has happened since 2008. There are these movements that have popped up - the Tea Party, Occupy, Moral Mondays, immigration marches, Arizona's SB 1070 and the response to 1070, the Dreamers. There's just been so much happening, and very little of it has been channeled into the Democratic Party. Some, but not all, on the right has been channeled into the Republican Party, clearly. We call it the Tea Party. And I think it's a big mistake if progressives don't do it in the Democratic Party.

OK, so, it's possible you could win next month.

I could win next month! Don't write that off.

OK, let me try again: But should the unforeseen happen, and Andrew Cuomo manages to pull this one out.

I know I'm an underdog, but I'm running to win .

If you don't, what next for you? I mean, you could have started off running for City Council, or the State Assembly.

Well, this was not the plan. Riding my bike when I was 7 years old, I did not say to myself: "I'm going to not run for office at all - and then I'm going to run for governor! That's my secret plan!"

So what was your secret plan?

I thought I'd get involved in electoral politics in a few years. A couple of years. The reason I am running now is because the situation requires it. The core old boy network in Albany is why no one else is running. Andrew Cuomo has been such a failure as a Democrat, that in an open system, someone would be running against him besides me. We have a serious structural problem in Albany, so it takes an outsider. I mean, look, almost nobody is talking about the Moreland scandal. And it's because they are dependent financially on the governor. Even the good politicians, of which there are many, are scared if they speak out against him it will hurt their constituents.

That was a factor in the Working Families endorsement, too, for unions whose members work for the state.

You could understand it, there were legitimate reasons . but if you're a state senator and you're afraid of executive vengeance and you can't run against the governor, you have a broken system. I've been writing about the Founding Era, one reason we had a revolution was the problem of "place men" - parliamentarians that did not represent their districts because they were so dependent on the king. These are fundamental, structural democratic problems.

But this race is really about the soul of the Democratic Party. Sometime in the '90s, traditional Democrats wandered. Most people still believe in public education. Most people believe in infrastructure. They believe in funding roads and bridges and transit systems. New York state is an embarrassment, that we're so far behind other transportation economies. They care about not poisoning their drinking water. A lot of Democrats have wandered off into Republican territory while carrying the Democratic name with them. They use the word "Democrat," but they do not believe in strong unions, they do not believe in strong public ed, they do not believe in infrastructure.

I find it extremely important to own our roots. I'm a progressive and a populist, but I'm a progressive and a populist in the vein of FDR. It's the corporate Democrats who have moved far right. You see our slogan - "traditional Democratic values, 21st century ideas."

I think Democrats like Bill Clinton - I still think Clinton had basic decent impulses, but he felt like he needed to throw off the baggage of the `60s and '70s, so he could do good things for people. But he never got to do very many of the good things. Those "new" Democrats never really developed a 1990s or early 2000s doctrine of what they were going to do for people - how were they going to build a new middle class, which was the project of FDR liberalism. Really, nothing has replaced that.

We do know concentration of power is a great driver of inequality. One thing we should do is stop the merger of Time Warner and Comcast. Another thing is to stop Amazon from declaring war on the publishing industry. A New York governor who cared about the New York publishing industry, which is a central New York industry, would be protecting that industry from an out of state company that is taking economic control. That is something FDR or Mario Cuomo would have recognized. But I think it's very exciting. I think we're in a big new anti-trust moment. That's coming out of Occupy, coming out of Moral Monday.

So you're out on the campaign trail talking to people about all of this.

And I love it.

Did you know you'd love it?

You know, politics is way undersold. It's so much fun. Our crowds are growing. First we were going to other people's events, now we're holding our own. People come with these questions about how their lives can be better, their families could be better, their businesses, how the state could be better. The job of politics is to take them from that question to action. And it's very moving. So we have a broken system but I don't think every politician is broken.

But the person who is taking me the most seriously in this state is Andrew Cuomo. I don't know what his internal polling is showing, but he tried to kick me off the ballot, and he failed, but he might be appealing that. He's sending interns around to follow me, and he took me seriously enough to become a Democrat again a few months ago [at the WFP convention].

Everyone's assumed Cuomo had a kind of Christie presidential strategy, if not for 2016, assuming Hillary runs, then after that: face no primary opposition, and then run up a big margin in the general election, winning over Republicans.

Andrew Cuomo is not going to be president. If there was any question before, there's no question now. To be president, you have to engage. After the Moreland Commission report, it was a scalding report. But you can survive a scalding report. But you can't survive five days of not answering questions. People expected him to come forward and say what he did, and why. They can choose to believe him or not. But hiding from basic questions does not get you a presidential nomination.

This has the potential to be the upset of the century. But it also has the potential to encourage people all around the country to run against corporate Democrats. Even a month out I can tell you we have changed politics in New York, just by opening it up and letting people know you can run. It has empowered people and I hope that we encourage tens of thousands of these kinds of races.

I'll tell you what happens to me all the time on the campaign trail. People say to me: "OK, I'll get my picture taken with you, I'll see what happens!" It's been a real exciting thing for people who are shut down or shut out because of the way Andrew Cuomo uses power: They see nothing terrible has happened to me yet!

[Joan Walsh is Salon's editor at large and the author of "What's the Matter With White People: Finding Our Way in the Next America."]

Spread the word