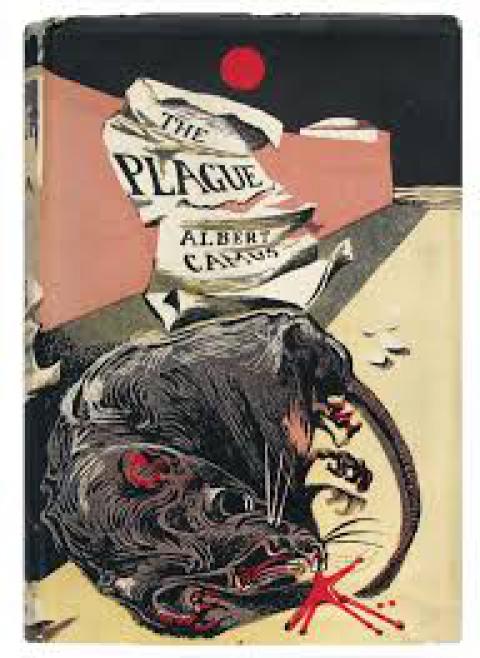

In his novel The Plague, Albert Camus describes how death comes to an ugly French port in Algeria.

Thanks to an infestation of rats and the fleas they carry, the bubonic plague descends upon the city in the spring and intensifies during the hot summer. After a short period of denial, the residents panic, then sink into despondency and alcoholism. The port is put under quarantine. Undeterred by the apathy of the population and the danger of exposure, a small number of courageous individuals mobilize to fight the epidemic and eventually beat back the invader.

Camus took great care to detail the symptoms of the disease. But for all his medical exactitude, the French writer was not primarily interested in epidemiology. His inspiration was a different kind of infection. The novel is set some time in the 1940s. The plague is Nazism, and those who fight the disease stand in for the heroes of the French Resistance. It is a supremely apt allegory, for did not the Nazis claim that their victims were vermin? Camus surely must have enjoyed reincarnating the German fascists as the lowest of the low: bloodsucking fleas and desperate rats.

The twin plagues of Nazism and bubonic plague, except for some isolated cases, are behind us. But now it seems that a different pair of plagues is in our midst.

Today’s headlines are filled with similar stories of the spread of death and destruction in the Middle East and Africa. American commentators worry that these plagues will burst their borders and somehow spread to these shores. And, as in Camus’s novel, these diseases point to something larger, not the imposition of a new malignant system but the breakdown of the existing order.

In West Africa, the plague is Ebola, a terrifying fever that ends in massive hemorrhaging. The mortality rate, if untreated, is as high as bubonic plague. But at least with the modern version of the Black Death, treatment brings the mortality rate down to 15 percent. Ebola, by contrast, resists treatment. There are no vaccines for this hemorrhagic fever—though there’s promising news out of Canada—and the few treatments that have been used remain highly experimental. Doctors and officials establish quarantines and hope the disease will burn itself out. With airlines shutting down service to the infected region, hampering efforts to deliver medical supplies, the disease continues to rage on.

Ebola has so far claimed around 1,500 lives. This is terrible, of course, but it pales in comparison to how many children succumb to diarrhea in Africa. According to a 2010 report, 2,000 African children die every day of a disease that can be prevented through relatively cheap methods: safe water and hygiene. But diarrhea is not a communicable disease in the same sense as the plague or Ebola. And no one in the United States worries that a summit of African leaders or the repatriation of infected patients will spread an epidemic of diarrhea stateside. Ebola monopolizes the headlines because what grabs attention is fear (along with the usual colonial images of Africans as dirty and irresponsible).

The panic is, of course, more acute in the areas hardest hit by Ebola. Consider the case of Kandeh Kamara, a brave 21-year-old who volunteered to help fight the disease in Sierra Leone. He was promptly drafted to become a “burial boy” responsible for dealing with the corpses of the infected. “In doing their jobs, the burial boys have been cast out of their communities because of fear that they will bring the virus home with them,” writes Adam Nossiter and Ben Solomon in a powerful piece in The New York Times. Talk about thankless tasks. Kandeh Kamara initially received no payment for his work and had to beg for food on the street. He now gets $6 a day and hopes to rent an apartment, though landlords often refuse to lease to the burial boys.

Ebola is bad news, but it hasn’t generated the same kind of fury as that other fast-spreading scourge, namely the Islamic State (IS). The recent beheading of US journalist James Foley has ratcheted up the outrage of American observers.

It’s certainly not the first beheading that IS has done. The group specializes in meting out barbarous punishments—decapitations, crucifixions, amputations. But just as Ebola’s impact became real for Americans when it infected people “like us”—two US missionaries in Liberia—the United States was prompted to act against IS when it began killing non-Muslims, first the stranded Yazidis and then the abducted journalist.

IS has spread quickly, and so has the panic that has accompanied its territorial acquisition. There have been the inevitable analogies to Nazism. But even those who don’t invoke Hitler are quick to use Manichean language to describe the IS challenge.

“We can see evil through the eye slits of the ski mask worn by Foley’s killer,” writes David Ignatius in a Washington Post commentary titled “The New Battle Against Evil.” “But stopping that evil is a harder task.”

The IS killers are a nasty piece of work, and their ideology is thoroughly malign. But I hesitate to use the language of good and evil. Such moralistic terminology presumes that they, the beheaders, are a Satanic force that can only be exorcised with whatever version of holy water our angelic forces dispense—air strikes, boots on the ground, military aid to the Kurdish peshmerga, efforts in the community to dissuade angry young men from taking the next flight to Mosul.

We, on the other hand, are good. We would never behead anyone. Those we execute “deserve” their punishment (though the occasional innocent person might inadvertently fall through the cracks). And the civilian casualties from our military offensives, because we are by definition good, are simply mistakes. After all, we don’t publicly celebrate the deaths of Afghan civilians from our drone strikes (forty-five in 2013 alone) or the deaths of over 400 children in Gaza. But our protestations of innocence are little consolation to the families of the victims.

At what point do mistakes aggregate into something evil? At the very least, do they prevent us from claiming the mantle of good? And, of course, it’s not just the mistakes that are problematic but also the deliberate policies that, for instance, align Washington with dictators and other murderous actors. American disgust with IS may already have prompted intelligence sharing with the regime in Damascus, though the Obama administration has denied such deals.

Camus had some choice words for those who are reluctant to call evil by its name. “Our townsfolk were like everybody else, wrapped up in themselves; in other words they were humanists: they disbelieved in pestilences,” he wrote in The Plague. “A pestilence isn’t a thing made to man’s measure; therefore we tell ourselves that pestilence is a mere bogy of the mind, a bad dream that will pass away. But it doesn’t always pass away and, from one bad dream to another, it is men who pass away, and the humanists first of all, because they haven’t taken their precautions.”

Humanists perhaps disbelieve in pestilences. “I used to not believe in evil,” confesses Richard Cohen this week in a Washington Post column declaring a “return of evil” with ISIS. Once a liberal humanist, Cohen long ago remade himself into a liberal hawk.

I still consider myself a humanist. But my brand of humanism sees pestilence everywhere. Indeed, I tend to see pestilence not only in the acts of individuals but in the structures within which the plague takes root and spreads. And this is where the two plagues intersect, Ebola and IS. They both prosper where the immune system is weak.

When it comes to medical infrastructure, Africa definitely has a compromised immune system. The continent has been hit hard by HIV/AIDS (70 percent of those living with HIV are in Africa), cholera (major outbreaks took place recently in Senegal, Zimbabwe and Sierra Leone), and malaria (an African child dies every minute from this disease). Ebola has spread rapidly because of critical shortages in medical staff and supplies.

But the deeper reason is environmental: the clear-cutting of forests that have served as a traditional barrier to pathogens. West Africa has one of the fastest rates of deforestation in the world, losing nearly a million hectares a year. The forests are Africa’s natural defenses, and Ebola is a sign that these defenses have been fatally weakened. What used to stay in remote villages now spreads quickly to urban areas.

The recent victories of IS in Syria and Iraq, meanwhile, suggest not a breakdown in the environmental system but in the political one. IS is not simply a band of serial killers. They have a distinct ideology and set of political motives. Nor does it matter whether they are operating in a formally dictatorial or democratic environment. IS thrives both where Assad rules with an iron fist and where Saddam is long gone.

The common denominator is chaos. IS has ruthlessly expanded in the gray areas beyond the reach of the rule of law. In Syria, it has prospered in regions that already broke loose from the country during the uprising. In Iraq, it took advantage of a paralyzing conflict between Shi’a and Sunni that left the northern reaches of the country tenuously connected to the central government.

Local governance, whether it’s democratic or authoritarian, serves the same function as the forests of West Africa. Such governance holds society together. When it deteriorates, the very cellular structure breaks down. In Ebola, the cell walls fray and the patient bleeds out. With a virus like IS, the fibers of the social fabric fray and large sections of the country bleed out.

There are, of course, many differences between a pestilence like Ebola and a movement like IS. But they are both the result of systemic breakdown. They are opportunistic infections.

In both cases there are no magic pills. Even if we come up with an antidote to this version of Ebola, as long as we continue to cut down the forests of Africa, more potent versions will continue to appear and spread. And if we attempt to obliterate IS only with bombs or boots on the ground, it will simply pop up somewhere else where the conditions favor such desperate efforts to create a totalitarian order. Instead we should focus on the conditions that give rise to these phenomena—and our role in helping to perpetuate these conditions.

Camus recommended vigilance. Pestilence, he concluded, “bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves and…perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.” The current plagues have certainly been a bane. Whether they also help to enlighten us remains to be seen.

Copyright c 2014 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by Agence Global. Please support our journalism. Get a digital subscription to The Nation for just $9.50.

Spread the word