There are few crusades in American politics more quixotic than bashing unions. They are a threat that exists mostly in the imaginations of their opponents: an all-powerful, resurgent labor movement that scares investors and imperils the economy, despite representing just 11% of the US workforce. Right-to-work laws are their weapon of choice.

Last week, the Supreme Court announced it would hear a case that could very well finish off American unions in the last bastion where they have any significant presence at all, the public sector. The case, Friedrichs v California Teachers Association, will decide if right-to-work laws (designed to bankrupt unions by encouraging employees who benefit from collective bargaining agreements to not pay for them) will extend to all public employees nationwide – an outcome Justice Samuel Alito has all but promised to deliver.

Lest you think such measures only target politically unpopular public sector unions, Illinois governor Bruce Rauner just announced he would create “right-to-work zones” for private businesses throughout the state, encouraging municipalities to follow Michigan and Indiana’s lead. Those two states were the latest to pass right-to-work laws in 2012, a remarkable shift in that last geographic stronghold of organized labor. Rauner contends that businesses, unshackled from the burden of union contracts, will rush to create jobs in Illinois communities – contrary to a University of Illinois study that found no such evidence for such a broad claim.

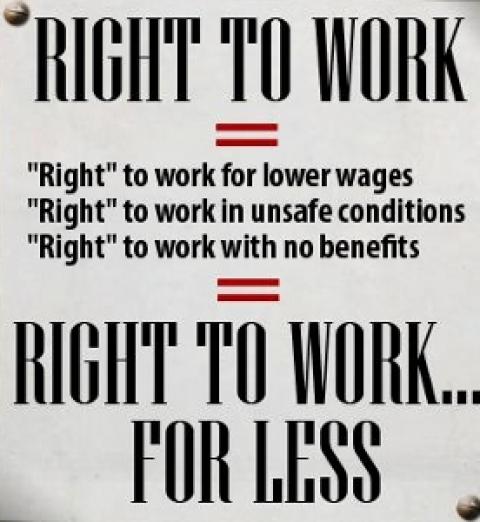

Economic arguments for right-to-work are, however, always highly speculative, proposing that the low-wage jobs that might be created by companies attracted by such laws would offset the very real, calculable income losses that inevitably accompany deunionization.

So if these laws don’t boost the economy, what else don’t they do?

Despite what their proponents say, right-to-work laws don’t put an end to “compulsory union membership.” There is no such thing, not since 1947, when closed shops – arrangements where union membership was a condition of employment – were banned under the Taft-Hartley Act. No one in the US can legally be fired for refusing to join a union, whether they are in a right-to-work state or not. Nor do such laws “protect” workers from having their dues diverted to political campaigns they do not support; workers already have that protection.

What right-to work laws do is ban a particular type of employment contract, voted on my employees, that requires all employees – union or not – to pay fair share provisions, a fraction of the dues that union members pay to cover the costs of negotiating and enforcing their contract. These contracts are borne out of US unions’ legal obligation to provide service to everyone, regardless of their membership status – including representing non-union workers in disciplinary cases, filing grievances and bargaining for the contract, the provisions of which (like salary schedules, pensions, vacations) will apply to all employees.

Thus, right-to-work laws simply discourage non-union employees in unionized workplaces from paying for the services they automatically receive, and financially cripple unions by denying them the revenue that pays for those services. The laws only restrict the money unions use to represent workers in the workplace – the very activities right-to-work proponents say unions should be restricted to doing – not the money that unions throw at politicians.

There is a great irony in small-government evangelists using the coercive power of the state to ban private contracts in the name of workers’ freedom – though it’s lost on right-wing groups like the Center for Individual Rights, the plaintiff in the Supreme Court case. When regulation takes the form of, say, occupational safety or anti-discrimination laws, such groups claim that they’re an infringement on freedom of contract. That freedom, apparently, only applies to contracts conservatives like – that is, those that favor employers.

Right-to-work laws illustrate the fundamental inconsistency at the heart of anti-union libertarianism. The outrage that small-government types voice in response to any infringement on individual liberties suddenly vanishes when those infringements happen in a workplace. And, as the saying goes, you get more orders from your boss in a day than you get from the government in a year. A boss can tell you what to wear, whom you can talk to, when you can go to the bathroom, can spy on you, and can fire you for any reason or no reason at all. You can be fired for smoking or drinking or having a haircut your boss doesn’t like, for being a Republican if your boss is a Democrat and, in many states, for being gay. The only notable protections against arbitrary dismissal are laws against certain types of discrimination (notoriously difficult to prove) and, of course, union contracts.

To people like Rauner, there’s nothing wrong with this, because when individuals sign employment contracts, they are to accept those contracts’ restrictions on their freedoms; the supposed sanctity of the contract trumps the proclaimed sanctity of individual rights. But conservatives then oppose union contracts because those contracts, and only those contracts, apparently infringe on a worker’s freedoms; the sanctity of individual rights trumps the sanctity of the contract.

Once you strip away the baseless economic and philosophical arguments, you’re left with the politics: politicians who want to help employers maintain the power they have over employees, by gutting any institution that might help employees tilt the balance in their direction. Whether you’re a boss or a governor, hobbling your opponents by any means necessary is smart strategy. Right-to-work laws are not so good at expanding freedom, but they are good at ensuring American workers remain disenfranchised in the one arena in which their rights are most restricted, eight or more hours a day, five or more days a week.

Spread the word