Love Control

The Hidden Story of Wonder Woman

Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948

By: Noah Berlatsky

Rutgers University Press, 2015

ISBN: 978-0-8135-6420-3

Wonder Woman Unbound: The Curious History of the

World’s Most Famous Heroine

By: Tim Hanley

Chicago Review Press, 2014

ISBN: 9781613749098

The Secret History of Wonder Woman

By: Jill Lepore

Knopf, 2014

ISBN: 9780385354042

by Kent Worcester

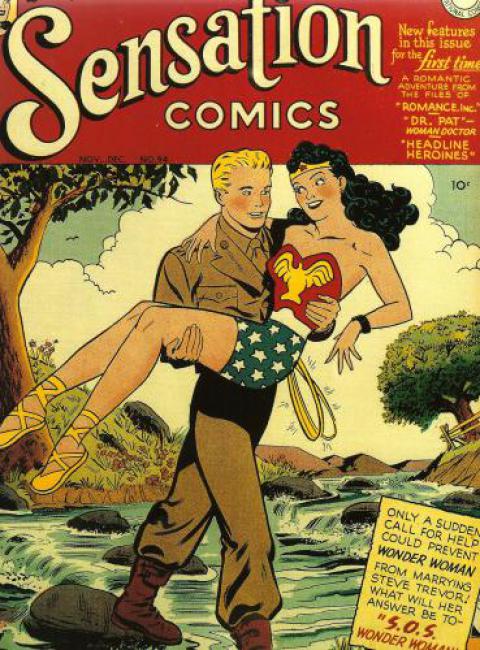

Wonder Woman was not the first female superhero, but she is the best known of the modern-day costumed heroines. Armed with indestructible bracelets, her Amazonian heritage, and a “magic lasso,” the character’s inaugural debut came in the pages of All Star Comics #8 in December 1941; a month later she was showcased on the cover of Sensation Comics #1. Seventy-five years on, Wonder Woman continues to appear in her own monthly comic book, as well as on innumerable licensed products, and the actress Gal Gadot is slated to play the character in the upcoming live-action movie Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Like her male counterparts Batman and Superman, Wonder Woman is a decades-old slice of intellectual property that also represents a cross-platform revenue stream with virtually unlimited potential.

When Wonder Woman first appeared on the newsstands she was one of literally hundreds of new pen-and-ink heroes designed to capitalize on the extraordinary success of Superman, whose circulation numbers skyrocketed in the late 1930s and early 1940s. While most of these superheroes were male, a smattering were female, including Fantomah; the Phantom Lady; the Red Tornado; Sheena, Queen of the Jungle; and Miss Fury. The emergence of these flamboyant characters coincided with the U.S. involvement in World War II and the rise of Rosie the Riveter, and Wonder Woman in particular became an emblem of female emancipation from hapless victimhood and conventional gender roles. From a commercial standpoint, she was probably the most successful of the comic-book female adventurers; while precise circulation numbers are hard to come by, it seems that some of her titles sold well over a million copies. At different points in the 1940s, she was featured in no fewer than four ongoing series—All-Star Comics, Comic Cavalcade, Sensation Comics, and Wonder Woman—as well as a short-lived newspaper comic strip. Ancillary companies proved eager to stamp her image on toys, clothing, and costume jewelry. The character remains a “license to print money,” as the media mogul Lew Grade once said about owning a television station.

Comic-book publishers have long been amenable the idea of turning print-based heroes, casts, and settings into licensed products and transportable franchises. Within a decade of his arrival, for example, Superman’s escapades had spawned radio plays, B-movies, and animated shorts. The Man from Krypton was even the subject of the first novelization of a comic book, George Lowther’s The Adventures of Superman (1942). Wonder Woman was perhaps not quite as generative, but her visibility and durability have long placed her in the first rank of superheroes. Indeed, over time she has come to symbolize the very idea of the female costumed hero. As the status of women has evolved within the confines of the “DC Universe,” and the society at large, so has the depiction and construction of the company’s only truly iconic female property.

A growing number of scholars are starting to write about superheroes, and it makes sense that a significant portion of their work is devoted to female superheroes, whose very existence raises interesting questions about social roles, social boundaries, and social hierarchies. The books under review here are part of this new wave of comics scholarship and have a great deal to say about the historical and biographical context that inspired Wonder Woman’s emergence along with the broader cultural shifts that her 75 years’ worth of history has recorded. In terms of style, methodology, and emphasis, they are decidedly different books, but they all hinge on an improbable real-life story, one that involves an enterprising academic, his close collaborators, and the startling assumptions that inspired his most famous initiative.

Golden Age superheroes were most often crafted by young men, many of them from New York City and Jewish. Wonder Woman’s waspy creator, William Moulton Marston, was an exception. As Tim Hanley reports, Marston (1893-1947) was nearly fifty when Wonder Woman first hit the newsstands, and he had earned no fewer than three degrees from Harvard: “a BA in 1915, a law degree in 1918, and a PhD in psychology in 1921.” By the late 1930s he had already made a name for himself through his books on human behavior, his public lectures, and his pivotal role in the development of the polygraph. “He was both an academic and a bit of a huckster,” Hanley says, “using his lie detector for noble purposes by assisting in criminal trials while also appearing in ads for Gillette razors to definitely prove they were the superior brand.” Marston was invited to join the editorial advisory board of All-American Publications after he had published an article in Family Circle that used advanced psychological theories to defend the fledgling comic-book medium. He then leveraged his industry connections to pitch a character called “Suprema the Wonder Woman.” Suprema’s name was shortened to Wonder Woman, and All-American Publications morphed into DC Comics, which for the past quarter-century has been owned by one of the world’s largest media conglomerates, Time Warner.

Female superheroes, then and now, tend to be fearless, tough, and a little generic. Wonder Woman is an altogether more exotic concoction, especially when Marston was writing her stories and overseeing her artwork. For one thing, the character came with an unusual backstory—Wonder Woman was raised on Paradise Island, where the Amazonians of pagan mythology lived in a separatist utopia that was entirely free of men and their baleful influence. Rather than being conceived via conventional means, her mother, Queen Hippolyte, “sculpted a baby daughter out of clay who was given life by the gods, and she named her Diana.” The Amazonian princess only learned about the outside world when a handsome U.S. fighter pilot, Steve Trevor, crash-landed on Paradise Island. As no man could remain on the island, Hippolyte’s daughter “flew Steve home in her invisible plane and established a secret identity as Diana Prince, Steve’s nurse and later his secretary, so she could stay close to her charge.” Hanley points out that when danger arose, “Diana Prince transformed into Wonder Woman and foiled the fiendish plans of whatever villain she encountered.”

Wonder Woman’s mythological roots are only part of what made the character distinctive. Even more unusual was the fact that Marston set out to create a self-consciously feminist heroine, one whose exploits could inspire girls and help boys come to terms with what Marston regarded as the obdurate fact of female superiority. “The future is woman’s. … Women will lead the world,” he wrote in 1942. “As a sex,” he insisted, women “are many times better equipped to assume emotional leadership than are males.” Or as he told the New York Times in 1937, “The next one hundred years will see the beginning of an American matriarchy—a nation of Amazons in the psychological rather than physical sense.” For Marston, “Superman and his army of male comics characters who resemble him satisfy the simple desire to be stronger and more powerful than anybody else. Wonder Woman satisfies the subconscious, elaborately disguised desire of males to be mastered by a woman who loves them.” In her original incarnation, at least, the character was designed to be the very best possible female superhero—wise, capable, and caring, as well as bullet defying and impossibly strong.

As Hanley shows in his informative survey of Wonder Woman’s appearances in comics, movies, and television, Marston’s radical vision for the character failed to live on after his untimely death from cancer in 1947. While the trappings of the character’s origin story were retained, messages of empowerment soon gave way to stories in which the Amazonian princess fretted over whether Steve Trevor would “pop the question.” As with Daily Planet journalist Lois Lane, the independent ethos of the war years gave way to cheerful domesticity in the 1950s and 1960s. This tonal shift not only played out in storylines and covers, but in the letters page and other supplemental texts. When Marston first introduced Wonder Woman, for example, he made a point of including a few pages’ worth of illustrated material that profiled “Wonder Women in History”—figures like Marie Curie, Clara Barton, Sacajawea, and Queen Margrete, a medieval Scandinavian ruler. After Marston’s passing, these backup pages addressed such vital topics as dancing, fashion, jewelry, and hairstyles. An issue from 1954 included one-page pieces on superstitions that “could break off an engagement, like a woman putting cream in her coffee before the sugar,” and “how doing up your buttons wrong would lead to bad luck all day.” While the character recovered her independent spirit in the 1970s and 1980s, contemporary Wonder Woman stories rarely give off the feminist spark that lend the original comics their unexpected resonance.

So who was William Moulton Marston? For many years, superhero fans could only offer vague biographical tidbits that raised as many questions as they answered. Thanks to Jill Lepore’s thoroughly researched “secret history,” we now know a great deal about the life and times of Wonder Woman’s creator and his circle. Moulton’s family traced its origins as far back as the Norman Conquest, and one of Moulton’s ancestors put his name to the Magna Carta. As an undergraduate, he was active in the Harvard Men’s League for Woman Suffrage, which had been founded by the radical writer John Reed in 1910. It was in this period that he met his future wife, Sadie Holloway, who was passionately committed to the feminist cause. Early in their marriage they made room for a third partner, Olive Byrne, a politically minded Tufts undergraduate whom Marston met when he was teaching in the psychology department there. As it happened, Byrne was also the favorite niece of the feminist speaker and birth control advocate Margaret Sanger. There were other lovers in Marston’s life, but he was devoted to Holloway and Byrne, and they were devoted to each other. “He had a rather strange appreciation of women,” cracked a DC Comics editor, many years later. “One was never enough.”

Marston, Holloway, and Byrne lived in a polyamorous relationship for more than two decades. Together they raised four children plus a menagerie of dogs, ducks, rabbits, and chickens. Two of the kids were Holloway’s, and the other two were Byrne’s, but the trio told the world-at-large, and their kids, that Byrne’s children had been adopted. After Marston’s death, Holloway and Byrne continued to cohabit, and their children eventually figured things out for themselves. Throughout their marriage, Holloway worked outside the home and coauthored books and articles with her husband, while Byrne looked after the children. Byrne also found time to write journalistic pieces and book reviews that cited Marston’s avant-garde ideas without acknowledging their intimate familiarity. Her first article for Family Circle was a cover-story profile of Marston entitled “Lie Detector.” “The big man saw me and smiled a welcome,” she wrote. “‘Hello,’ he said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you.’” In a subsequent article, she gushed that “No one can feel shy in Dr. Marston’s presence. He is the sort who brushes away social artificialities and makes you feel completely at ease.” As Lepore wryly notes, Byrne failed to inform her readers “that she’d known him for ten years and lived with him for nine.” Even as Marston’s celebrity grew, his family managed to keep their unorthodox arrangement to themselves.

It must have been quite a household. Lepore, who has a novelist’s eye for detail, has poured through the relevant archives and private correspondence, and conducted lengthy interviews with surviving friends and family. The result is a portrait of gentile midcentury eccentricity that leaves little to the imagination, with the courteous exception of their sex lives. When he was writing Wonder Woman stories, for example, Marston occupied “the study on the second floor” and “mainly worked lying on a daybed, wearing nothing but his underwear, a sleeveless undershirt, and slippers.” He had “grown gigantic. He weighed more than three hundred pounds,” and when he got out of bed, “the floorboards creaked. He smoked Philip Morris cigarettes, from cans of fifty,” and “drank rye and ginger ale, morning and night.” As a father he was “passionately affectionate,” Lepore adds. At bedtime he insisted that his only daughter “enter his study, say, ‘Goodnight Daddy,’ and kiss him on the mouth. Every night, she refused. ‘For Christ’s sake,’ Olive would say, ‘just run in there and kiss him quick and get it over with.’” Marston “administered IQ tests to each of his children,” and “promptly informed the children of their scores.” He was “the loudest person in the house, but he was also the most ridiculous,” Lepore writes. “He’d fume and he’d storm and he’d holler, and the women would whisper to the children, ‘It’s best to ignore him.’”

The “loudest person in the house” was not exactly shy about using Wonder Woman to advance his agenda. When he first proposed a new female superhero, his publisher suggested that female heroes were a tough sell in the comic-book marketplace. “But they weren’t superwomen,” Marston argued back. “They weren’t superior to men.” A male hero, he explained, “lacks the maternal love and tenderness which are as essential to a normal child as the breath of life. … The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with all the strength of Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman.” As he later told reporters, Wonder Woman represented “the new type of woman who, I believe, should rule the world.” To bring the Amazonian to life, Marston insisted on using artwork by Harry G. Peter, who at the age of 61 was “an antique by comic-book standards.” Peter’s figure work was stiff, and his compositions were stagey. But his visual style harked back to suffragette imagery from the 1910s and 1920s, and he excelled at drawing the blindfolds, chains, ropes, and traps that regularly turned up in Marston’s fanciful stories. According to Lepore, “Marston’s control over the final product is suggested in the scripts themselves,” which typically included strict instructions about “page layouts, panels, and color choices.”

In her early stories, Wonder Woman was sometimes a fighter but more often a peacemaker. Her stories tended to revolve around the theme of rehabilitation rather than vengeance. She could throw a punch but preferred to convince wrongdoers to see the error of their ways. Her tools were protective rather than aggressive—bullet-deflecting bracelets, an invisible plane, and a golden lasso that could wring a confession out of the sourest of miscreants. Wonder Woman often shared the stage with a coterie of young women from the fictional Holliday College—sisterhood in action, as it were. She also spent quite a bit of time being tied up, sometimes by friends but mainly by her adversaries. “Not a comic book in which Wonder Woman appeared,” Lepore finds, “lacked a scene of bondage”:

In episode after episode, Wonder Woman is chained, bound, gagged, lassoed, tied, fettered, and manacled. She’s locked in an electric cage. She’s winched into a straitjacket, from head to toe. Her eyes and mouth are taped shut. She’s roped and then confined in a glass box and dropped into the ocean. She’s locked in a bank vault. She’s tied to railroad tracks. She’s pinned to a wall. Once, so that she can be both entirely bound and movable, her fettered feet are welded to roller skates. “Great girdle of Aphrodite!” she cries. “Am I tired of being tied up!”

None of this was accidental, or even incidental; from Marston’s perspective, these stories were intended to instruct young readers about the difference between brutal coercion and what Lepore terms “the enjoyment of submission to loving authority.” In a memo to his publisher, Marston averred that the “only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound—enjoy submission to kind authority, wise authority, not merely tolerate such submission. Wars will only cease when humans enjoy being bound.” (Emphasis in the original.) For Marston, there was a world of difference between what he described as “harmful, destructive, morbid erotic fixations,” and healthy role-playing. “My basic idea,” Marston explained to his publisher, involves “women fighting male dominance, cruelty, savagery, and war-making with love control backed by force.” The most elaborate displays of bondage in these stories were performed by the denizens of Paradise Island, that is, by women who ritualistically tied each other up during lusty ceremonies that celebrated female power and autonomy, rather than by the saboteurs and criminals against whom Diana Prince and Steve Trevor battled. In Marston’s comics, sadism was always wrong, and must never triumph, whereas the good kind of bondage, domination, and submission could help friends and lovers express their true selves and thereby transform the world.

While Lepore acknowledges Marston’s storytelling fixations, she seems far more interested in his family shenanigans and academic mishaps than in the comics themselves. Thankfully, Noah Berlatsky’s theoretically informed analysis of Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics provides a close reading of the early Wonder Woman stories and fills in some of the gaps left by Lepore’s ironic detachment. Drawing on the writings of Jacques Lacan, Janice Radway, Judith Butler, and others, Berlatsky argues that Marston “created a universe that was friendly to queer sexualities and lifestyles, from kink to lesbianism to crossdressing.” Marston’s “most important themes,” Berlatsky suggests, are “feminism, pacifism, and queerness—or if you prefer, bondage, violence, and heterosexuality.” His comics-centric study zeroes in on these hot-button themes and makes it clear just how atypical Marston’s stories were in relationship to the superhero genre as a whole. In so doing, Berlatsky makes a persuasive case for the claim that “Wonder Woman, the original comic, was much more interesting, beautiful, and worthwhile than Wonder Woman the popular icon.”

Spread the word