labor Connecting the Dots Between the “Identity Politics” of Black Lives Matter and Class Politics

“We like to think of class as the empirical, tangible idea behind everything else. You know, there’s race, gender, sexuality, and all the other social differences that we sometimes derisively refer to as ‘identity politics,’ but class is the real thing” said Jelani Cobb, Director of Africana Studies at the University of Connecticut and moderator of “Black Lives Matter/Fight for $15: A New Social Movement,” held October 19 at the CUNY Murphy Institute for Worker Education and co-sponsored by the Sidney Hillman Foundation.

Cobb, who was joined by #BlackLivesMatter co-creator Alicia Garza and Fight4$15 organizing director Kendall Fells, continued, “But if we look at this narrative and the history of labor, we find ‘identity politics’ popping up again and again. My mother was a domestic worker. Under the [1935 Social Security Act], she was ineligible for benefits, a concession to Southern Democrats. For her, these questions were not abstract. Her exploitation as a woman, her exploitation as a black person, and her exploitation as a worker were intricately connected and woven together.”

The question of the relative importance of class versus other markers of identity, such as race, gender or sexuality, has often divided the Left throughout its history, but on this chilly October morning, all three speakers were in agreement: The problems facing black people in America are inseparable from the question of class and exploitation and vice versa.

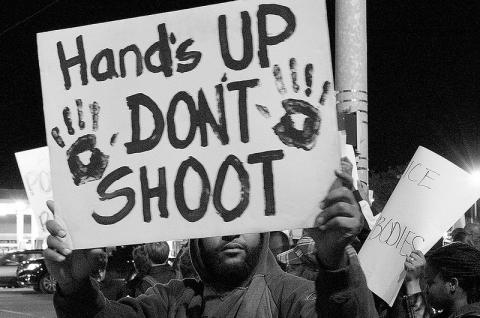

“What we are fighting around are the contours of black life,” Garza said, attempting to define the broad mission of Black Lives Matter. “We do work around policing and criminal justice, but we also take on development, affordable housing and gentrification, gender justice, trans liberation, economic justice, anti-austerity and privatization, climate justice, education, corporate accountability, and rights, dignity, and respect for gay, lesbian, and bisexual folks, because all of these issues shape the contours of black life. We’re fighting back against anti-Black racism, but we’re also fighting for dignity and equality for all persons.”

Likewise, Fells highlighted the ways in which Fight for $15 is about much more than $15 and a union. The typical fast food worker, he noted, is a single mother of color, struggling to feed a family and pay rent. In fact, Fight for $15 originally grew out of an organizing effort for affordable housing. In 2012, Fells was working with New York Communities for Change, an advocacy group pushing for education and housing justice in New York City, collecting signatures from low-wage workers for a petition on affordable housing. When organizers followed up with the workers, they started to realize that they couldn’t address housing without looking at wages and jobs.

“A lot of them couldn’t even get to affordable housing, they were so far in poverty. They were sleeping in homeless shelters, couch-surfing, even though they were working one, two, three jobs,” Fells said.

In fact, as both Fells and Garza agreed, black women have provided the backbone for both Black Lives Matter and Fight for $15. Garza offered the example of Jeanina Jenkins, a 19-year-old employee at the McDonald’s in Ferguson, Missouri. Before the killing of Mike Brown, Jenkins had been an active member of Show Me 15, the local Fight for $15 chapter, getting arrested for trespassing with other Show Me 15 activists at a McDonald’s shareholder meeting in May 2014. After Brown’s death, Jenkins was one of the first people out on the streets, helping to lead protests in front of the Ferguson Police Department.

“She was very clear about what the connection was. I asked her, ‘How are you doing both things? During the day, you’re organizing for $15 and a union, and at night, you’re in front of the Ferguson Police Department. Why?” Garza said. Jenkins’ response was simple: “Poor communities are underpaid and overpoliced. And too often those communities are black and brown.”

Garza also drew attention to the disparity between the overwhelming participation rate of black women in organized labor—making up 14.7 percent of all union workers, according to “And Still I Rise,” a recent report on black women in the labor movement—and their underrepresentation in positions of leadership. Changing this, she said, is important not only for fairness; it’s also crucial for strengthening organized labor as a whole.

“The relationship between organized labor and black folks has always been one where black people have lent an increasingly radical edge and have provided again and again a compass for where the soul of this country should go,” Garza said.

The point, both Garza and Fells emphasized, is that “identity politics” and class-based politics have to go hand in hand, if either is to be effective.

“There is space for us to fight along multiple dimension at once. We don’t have to pick one. I don’t have to be a worker today, a queer person tomorrow, a woman tonight. I can be all of those things, all at once, hallelujah,” Garza said. “It’s not about identity politics. It’s about our lives. The very sanctity of our lives is at stake. We have nothing to lose and everything to gain.”

Spread the word