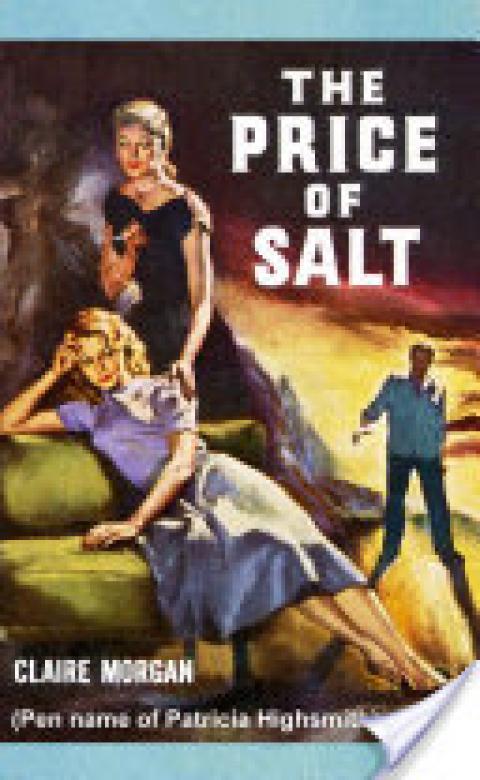

The Price of Salt: OR Carol

Patricia Highsmith

Dover Publications

ISBN: 9780486800295

Patricia Highsmith is first and foremost a crime writer. Her best known novels—Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley—are psychological thrillers in which she aligns us with a criminal protagonist, implicating us by blurring the thin line between desire and transgressive illegal and immoral behavior. Her second novel The Price of Salt, on which the new Todd Haynes film Carol starring Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara is based, is an anomaly for her. By definition, it’s not a crime novel; however, it contains an exploration of transgressive desire that has resonance with the criminal behavior in her best known crime novels.

Originally published in 1952 under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, The Price of Salt is the story of a romance between two women, Therese Belivet, a nineteen-year-old aspiring theater set designer, and Carol Aird, an elegant and affluent woman in her thirties, who is in the midst of a divorce. Highsmith tells the story from Therese’s perspective, and Therese’s attraction to Carol is immediate and intense. Despite the social and professional ramifications, Therese pursues the older woman unflinchingly. She knows what she wants. During a time when society would label her desire as mental illness or discount it as lingering adolescent confusion, such confident self-understanding is remarkable.

Carol returns Therese’s advances with caution and tenderness. The two women circle one another for two-thirds of the novel, observing and desiring, but not consummating their relationship until their emotional bond has been well established. This vibrant, at times unsettling, tension is unmistakably Highsmith. During Therese’s first visit to Carol’s large suburban home, Carol puts Therese to bed and serves her warm milk. It’s a wonderfully odd scene, both suggestive of a mother-daughter relationship and tinged with fairytale imagery—“Therese drank [the milk] down, as people in fairy tales drink a potion that will transform, or the unsuspecting warrior the cup that will kill.” It will be nearly 130 pages before they have sex, but in this scene, something deeply intimate and transgressive is already occurring. They’re slowly straining against the boundaries of propriety, against the conservative framework of their time and place. They have much to lose by falling in love—Therese, her boyfriend and stability, and Carol, her financial security and her daughter, of whom her husband wants full custody. However, the danger of this transgression doesn’t discourage them; it fuels them. Like the milk Carol is offering Therese, it could transform them or kill them—and that tension, that deep curiosity, serves as foreplay, fertile ground for a complex love. After they have sex for the first time, Therese asks Carol why she a waited so long, and Carol says, “Because—I thought there wouldn’t be a second time, that I wouldn’t want it. But that’s not true.” Like Therese’s earlier thought about the milk, Carol reveals to us that she too desires and fears transformation—a transformation that can only come by way of a transgression.

This desire to transform through a transgression is something Therese and Carol have in common with Tom Ripley from Highsmith’s Ripley series and, a bit more obliquely, Guy Haines from Strangers on a Train. Although unlike Ripley and Haines, Therese and Carol never commit a murder or even a violent act, Highsmith has woven a sense of menace through the novel. Therese’s attraction to Carol is often characterized in violent terms: “Therese looked up at her, unable to bear her eyes now but bearing them nevertheless, not caring if she died that instant, if Carol strangled her, prostrate and vulnerable in her bed.” When they have sex, Therese imagines herself as an arrow that “seemed to cross an impossibly wide abyss with ease, seemed to arc on and on in space, and not quite stop.” It’s a gorgeous extended metaphor, so gorgeous it’s easy to overlook Therese’s thinking of her body as a weapon. The logic goes: if weapons are tools of violence and through violence comes transformation, then Therese’s body is a weapon that she must use to become who she really is. It’s an uncomfortable logic, which Highsmith brilliantly weaved into the DNA of her best fiction.

But the threat of violence isn’t just metaphorical or psychological. Soon after the lovers set out on their trip west, Therese finds a gun in Carol’s possession. Before long, they discover they’re being followed by a detective hired by Carol’s husband. They are being pursued as criminals—after all same-sex sexual acts are illegal at this time—and as they become more aware of the danger of their transgression, their anxiety heightens and sex becomes more passionate, rougher. When in the shower together, “Therese wanted to embrace her, kiss her, but her free arm reached out convulsively and dragged Carol’s head against her, under the steam of water, and there was the horrible sound of a foot slipping.” As external forces bear down on them, they clash more passionately (and violently) into one another.

Highsmith, who had relationships with women and men, found inspiration for The Price of Salt in a chance encounter with Kathleen Senn, an elegant, mink-swathed customer at Bloomingdale’s where Highsmith worked briefly. In a journal entry excerpted by Joan Schenkar in her excellent biography, The Talented Miss Highsmith, Highsmith writes about Senn: “For the curious thing yesterday is I felt quite close to murder, as I went to see the house of the woman who almost made me love her when I saw her a moment in December, 1948. Murder is a kind of making love, a kind of possessing.”

Sex and violence are linked, because in Highsmith’s fictional world, they are often social, legal, and moral transgressions. Carol’s and Therese’s sexual connection, like Ripley’s or Haines’ murderous actions, allow them to transform themselves, to move beyond social and moral standards and find a new freedom. We can embrace Carol’s and Therese’s choices more readily than Ripley’s and Haines’ choices, of course. Highsmith’s genius is that she saw freedom, despite the consequences, as heroic, perhaps that’s why we fall in love Therese and Carol as they fall in love with one another, and why we identify with Ripley and Haines, even as they commit murder. Something in us, despite the particular social, legal, or moral parameters set before us, understands this desire for freedom.

Spread the word