“I’m Going to Learn to Dance If It Takes Me All Night and Day” - Thoughts on Chuck Berry

The silence of pro-working class political organizations of the Left, and of the unions, regarding early rock and roll is striking. This is more surprising in retrospect than it was at the time (the McCarthy era constraints operating here deserve a separate treatment all their own), yet the fact remains that early rock and roll was the most thoroughly working class intervention into mainstream culture that our society had yet seen. The music troubled custodians of working class interests because it was essentially non-ideological and amoral. If radicals, Communists, Socialists, social democrats, and liberals agreed on anything, it was on the value of the Puritan-Fordist work ethic, the virtue of the ordered and disciplined life, and on the idea that all could be made right once we found the proper relationship between society’s institutions and the “real” interests of the working class.

Rock and roll would have none of it, as the 1950s songs Berry wrote and recorded demonstrate. (My six one-liner posts above, and the title to this post, are all quotations from Berry songs I discuss here.) Many of his songs express opposition to alienated labor and its attendant society. “School Day,” for example, portrays the school itself as the problem. It subjects the institution as such to a withering critique, exposing school as little more than a nasty training ground for the nastier world of work, which, of course, it is; but no teen in 1957 needed a sociologist to get that message. All they had to do was listen to the radio. “Brown Eyed Handsome Man,” starts with the tale of a victorious encounter with the racist criminal justice system (the term of art is “vagrancy”), and proceeds with a kind of black history lesson. (Those who think the eye in this song isn’t a metaphor should listen again.) “Brown Eyed” includes a nod to miscegenation and ends with a vignette about a heroic baseball player. Astute listeners would have thought of the famed, just-retired Brooklyn Dodgers second baseman whose press notices might have had the words “brown,” referring to persons, and “handsome,” in the same sentence. On the other hand, must I explain “rotten bill,” in “Too Much Monkey Business”? Or what it means to face such a thing after a week of hard work? We don’t find such references in Cole Porter songs. Nor do we find challenges to state power itself, such as that in “You Can’t Catch Me,” where the singer, now driving a “Flight de Ville,” mocks the state police at the New Jersey-Pennsylvania border. This is closer to the beboppers’ idea of “disorder at the border” than it is to any left wing or right wing concept of “labor discipline.”

People talk about how influential Berry was, but the credit he’s given is often limited. Sure, he’s cited as a rock and roll pioneer, but when listening to a “dream” song like “Downbound Train,” I’m reminded that what’s called the “Folk Revival” of the early 1960s came in Berry’s wake as well. So tell me which folkster has covered this song. Or, perhaps more important, which one of them has based a song of their own on this one. I’m hearing echoes, but I won’t name them. You can name them yourself.

Let me offer some final observations, having to do with rhythm and sound. There are some pop drummers who want to call attention to themselves, who think rock and roll drumming is about displaying one’s emotions. I say that if you want to be an emotional drummer, look to Elvin Jones, or Max Roach, or even Chick Webb for inspiration. Yet however emotional these musicians might be, they also know a cardinal value that listeners treasure in drummers. The best drummers are felt, not heard. One could write an entire essay on the emotional content of Roach’s solo on Charlie Parker’s 1945 recording of “Ko Ko,” but what Roach does there has no place in rock and roll. On the other hand, what Ebby Hardy and the great, vastly under appreciated Fred Below do on Berry’s early records only seems simple enough. They bang the hell out of the beat. You might think it sounds mechanical, and it does; but I cannot help but think this characteristic reflects the world of work. To put it another way, when listening to these records, imagine yourself in a hot, nasty, noisy factory, assaulted all day by the steady pounding of machines. Then imagine dancing your way into nirvana at night to that same pounding, only now it’s in the service of guiding your body into joyous ecstasy. Imagine that this has never happened before now.

The machine-like sound in Berry’s music — found in his guitar playing as well — can be understood as one way 1950s blues reflected the proletarianization of African American (and other) workers. In this sense, the similarities between early records by John Lee Hooker and Berry’s efforts, in terms of both rhythm and guitar sound, are instructive.

For all that though, we need just one simple test to gauge Berry’s significance. Imagine the last seven decades without him. Such a world would have been vastly unlike the one we know. Chuck Berry didn’t just change a musical style. He changed what we mean when we use the word “music,” and thereby he enriched human culture as such. For that, society will always gratefully remember him.

[Geoffrey Jacques is a poet, critic, and teacher who writes about literature, the visual arts, and culture. His research interests include modernist poetry and poetics, African American literature and culture, and the postmodern city.]

Chuck Berry - 1926 - 2017 - A Musical Selection

Maybellene - Live Performance (1958)

Listen here.

Schools Days

Listen here.

Roll Over, Beethoven - 1972 Live Performance

Listen here.

Johnny B. Goode

Listen here.

No Particular Place to Go

Listen here.

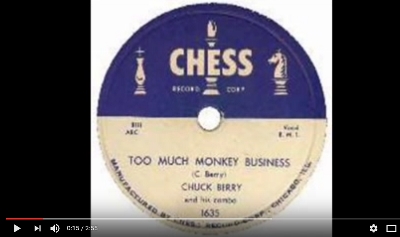

Too Much Monkey Business

Listen here.

Promise Land

Listen here.

Nadine (Performed with Keith Richards)

Listen here.

Beautiful Delilah

Listen here.

Memphis, Tennessee (Performed with John Lennon)

Listen here.

Rock 'n Roll Music (Performed with Tina Turner)

Listen here.

Spread the word