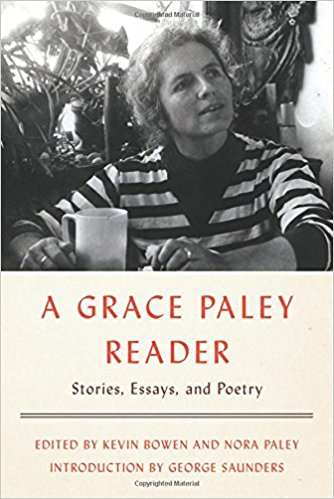

books The Stubborn Optimist: Following the Persevering Example of the Writer and Activist Grace Paley

Kevin Bowen and Nora Paley, editors

Macmillan/Farrar, Strause and Giroux, 400 pages

Hardcover: $27.00

April 18, 2017

ISBN: 9780374165826

It is the early 1930s. A girl in New York City, just tall enough to see over her family's kitchen table, catches a moment of tacit communication between her parents. The mother pauses in her reading of the newspaper to say to the father: "Zenya, it's coming again." Even the young girl, Grace Goodside, knows what "it" means: Hitler's rise to power. The "again" was more mysterious-more compelling-both for the girl and for Grace Paley, the writer and activist she became, who retold this memory. The 1905 pogroms that killed her uncle and drove her parents from Russia to the United States were only dimly known to her as a child. A penumbral and weighty silence, common to refugees from politically murderous areas of the globe, covered much of the family's past in the old country. A lesson emerged from that parental shorthand "again"-namely that nothing, even the worst, was entirely new. Politics was a matter of taking the long view and enduring.

Paley never forgot the rebuke her parents' wariness offered to American innocence, but she lived to shatter the silence with the volubility of an American child. From her Bronx childhood to her maturity in Greenwich Village's radical heyday, lasting to the Vermont retreat of her old age and her death in 2007, Paley was a fearless and unflagging arguer. She was someone who gained energy through the give-and-take of political debate, whose brash, blunt New York manners made the tacit sayable. A co-founder of the Greenwich Village Peace Center and a noted member of the War Resisters League whose pacifism was rooted in a continually evolving feminism, Paley blended the socialism of her secular Jewish upbringing with the unruly passions of the left during and after Vietnam: The civil-rights, antiwar, and environmental movements each counted her as an ally. Much of her arguing happened on the ground-at protests, at the constant meetings that her life as an activist demanded, during visits abroad to nations that her own country was spending its young men and money ravaging. But from the 1950s until the 2000s, much of it also happened in writing: in poetry, in essays and political reportage, and in short stories, where her brilliance found its best outlet.

Politics is a matter of taking the long view and enduring.

Paley's oeuvre isn't large. Years raising children, and many more years as a committed political actor, limited the extended solitude that writing demands. The short stories came out in three books published over two and a half decades, while the essays and poems were scattered over a longer period of time. The career can fit between two covers, as in a multi-genre anthology like A Grace Paley Reader. If the Reader was intended as a memorial, published a decade after her death, it now seems more pressing - a necessary antidote to the current demoralization of the American left and the disorientation of what remains of the country's center. On the one hand, Paley's durable, disabused optimism and the resilience of her fiction's women, "the soft-speaking tough souls of anarchy," as she called them in the story "Friends," will catch you up short. On the other hand, so will her wary fatalism, the voice that lingered from her parents, reminding her how "it"-illiberalism, authoritarianism, the scapegoating of the most vulnerable-always might, and usually does, come again. When that happens, as it now seems to be happening, Paley has a way of reminding us how to be stubborn.

Paley's initial stories, slowly written during the 1950s and collected in The Little Disturbances of Man in 1959, received the kind of attention that launches careers. It is not hard to see why. They are masterpieces of voice, stunning ventriloquisms of women who, telling their life stories, refuse to be taken for suckers in a man's world. A streetwise Russian-Jewish Bronx patois is the general dialect, but every utterance of her characters promises to take an idiosyncratic, poetic swerve. The 14-year-old narrator of "A Woman, Young and Old," on her mother's taking a new lover: "Living as I do on a turnpike of discouragement, I am glad to hear the incessant happy noises in the next room." The middle-aged Aunt Rose of "Goodbye and Good Luck," remembering taking up piecework flower-making to earn some money as a young woman: "This was my independence, Lillie dear, blooming, but it didn't have no roots and its face was paper." With stony bravura, "An Interest in Life" opens: "My husband gave me a broom one Christmas. This wasn't right. No one can tell me it was meant kindly."

The milieu is the New York City immigrant world that muddled along before and during World War II, and then lurched unpredictably into middle-class prosperity. The voices are unapologetically female, speaking as if woman-to-woman. Men are transients and incidentals, "till time's end, trying to get away in one piece," Aunt Rose comments. Crowded multigenerational homes and thin walls make sex a common preoccupation. Patriarchal rules, inevitable and sublimely ridiculous, turn women into rugged survivalists. By 1959 this display of voice-the comedy of white ethnic life-was somewhat recognizable territory. Still, Paley pulled it off with so much panache that it gained her a following. The rueful honesty of her female narrators gave the stories a political charge, but they could be read as merely brilliant, wicked mimicry, a kind of amusing tourism, their feminism latent.

Late in The Little Disturbances, however, Paley found the key to transcending comic-ethnic ventriloquism: the recurring character Faith Darwin Asbury. While Paley's other narrators speak as if unconscious of their picturesque wit, Faith-a single mother of two boys, juggling petit bourgeois drudgery in increasingly bohemian times, putting no stock in men or their work-is her author's equal. The joke is no longer for the reader; it might even be on the reader. From her first appearance in "Two Short Sad Stories From a Long and Happy Life," when she names her first and second husbands Livid and Pallid, Faith has a self-awareness that makes it impossible to laugh at her:

Truthfully, Mondays through Fridays-because of success at work-my ego is hot; I am a star; whoever can be warmed by me, I may oblige. The flat scale stones of abuse that fly into that speedy atmosphere are utterly consumed. Untouched, I glow my little thermodynamic way.

On Saturday mornings in my own home, however, I face the sociological law called the Obtrusion of Incontrovertibles.

Faith invites and refuses confidences in the same sentence: "I rarely express my opinion on any serious matter," she tells us, "but only live out my destiny, which is to be, until my expiration date, laughingly the servant of man." If the admission seems like a bitter acceptance of things as they are, it is also the beginning of a refusal. It is a bulletin from a developing front.

Through faith, Paley discovered her great subject: the evolving political engagement of the generation of women who came of age in the shadow of World War II. The stories Paley wrote after The Little Disturbances are ever more plotless. They are snapshots of female community-in particular, the group of Greenwich Village women early to the postwar quest for feminist consciousness-or, in Faith's own words, "a report on . the condition of our lifelong attachments." Paley borrowed the method of linking characters across a story series from Isaac Babel, one of her lodestars. But unlike Babel's Odessa stories - or, for that matter, Sherwood Anderson's Winesburg, Ohio - Paley's stories about Faith extend the timescale well into adulthood. Faith and her friends age, shedding lovers and children and parents, and finding new objects for their political passions. It turns out that rather than voice, Paley's true subject was time.

Put another way, her theme was how the ethical aspirations of political life extend over time: how they survive inevitable disappointment; how they steel themselves into endurance. Paley's second collection, 1974's Enormous Changes at the Last Minute, was like nothing else in American writing then. Especially startling was the way the stories handled the question of time. "Faith in a Tree," one of the volume's showstopping pieces, starts as a gently meandering account of a Saturday afternoon in Washington Square Park, where Faith observes other mothers, the new generation of fathers performing parental attentiveness, the hesitant mixture of races, the urban gossip and sexual competitiveness. Faith's voice is mordantly witty but sympathetic. The park is, as she puts it, "a place in democratic time," and there is love blended with Faith's quiet acerbity.

The story seems for a while like the kind of observational vignette that might have made its way into William Shawn's New Yorker, a poignant display of modern manners in the style of Irwin Shaw or John Updike - and then the story tears itself apart. A small procession of families enters the park making noise and carrying signs protesting the napalming of Vietnamese villages. A picture of a "seared, scarred" baby is borne aloft. A policeman forces them out of the park. Faith fails to intervene on their behalf; her older son accuses her of timidity. In a moment, everything is different: "And I think that is exactly when events turned me around, changing my hairdo, my job uptown, my style of living and telling . I thought more and more and every day about the world."

The story doesn't merely explode the comfortable confines of white-collar realism. It refuses the blandishments of postmodern irony, another popular narrative mode in 1974. After all its emotional indirection and leisured byplay, its well-mannered literariness, Faith's last words register with a stunning, almost embarrassing directness. The story lingers, and then pounces, transformed into a confrontation with a political fact; one moment expands suddenly into years, pulling us into a future of continual preoccupation. More and more, starting in the late 1960s, Paley's stories worked like this-embedding us in slow daily time in order to confront us, obliquely or directly, with urgent historical time. They depict the frictions of changing social norms, but they also preach, particularly the virtue of endurance. It is Paley's emotional signature: how to wait patiently, stubbornly, but not passively.

"My husband gave me a broom one Christmas. This wasn't right."

The transformation from the early stories is remarkable, a pivot from wit into something like a steady and intelligent earnestness. Earnestness, above all, is durable. Hate burns itself out and exhausts; indignation yields eventually to acclimatization; hope is bound to be disappointed. Earnestness expects to be around for a while, and knows it won't have it easy. This is the theme of Paley's essays, which offer plainspoken accounts of resistance: a jail stint for civil disobedience; a 1969 trip to North Vietnam to escort three American prisoners of war home; protests at the Seneca Army Depot, at the Pentagon, on Wall Street. The essays are not rousing, precisely, or in any way histrionic. They are steely. In their own way they too are about the long game, the lifelong project of change.

At the Seneca protest in 1983, Paley, then 60, musters one more act of exhilarating athletic defiance and climbs a fence around the Army depot. She is arrested for it, but claims no special virtue for the effort. "There was a physical delight in the climbing act," she reports,

but I knew and still believe that the serious act was to sit, as many women did, in little circles through the drenching night and blazing day on the hot cement in front of the truck gate with the dwindling but still enraged "Nuke Them Till They Glow" group screaming "Lesbian bitches" from their flag-enfolded cars.

There are no easy conversions here, and while Paley has a stern understanding of her political enemies, she refuses to soften into acceptance. Instead she dwells on protracted acts: long, difficult conversations; long, painful vigils; many drenching nights and blazing days without obvious results. They are what the stories give us, fragmented into brief, vivid glimpses. Of the voices of mid-century American radicalism, few could ever make perseverance seem so vital.

[Reviewer Nicholas Dames is the Theodore Kahan Professor of Humanities at Columbia University and the author of two books on Victorian fiction.]

Spread the word