So, the General Election happened. That was fun. What was meant to be a Conservative landslide turned into a chaotic hung Parliament situation. A lot of the blame for this surprising (hilarious) result has been placed on an unexpectedly large increase in turnout from pro-Labour younger voters. And I do mean “blame”, because according to many, this was something they shouldn’t have happened, because younger people can’t be trusted to make such important decisions. Apparently.

Seriously, there have been phone-ins about it. Many articles. Letters to the editor. Lord knows how many below-the-line comments. All based around the point that young people voting is bad, and they shouldn’t do it, for reasons. Presumably many of these reasons a variations of “how they vote doesn’t correspond with how I’d vote and I cannot allow this”, but are there any valid ones? As in, scientifically speaking, are there any realistic arguments for younger people being denied a vote? Here are a few candidates

Young people’s brains haven’t finished forming yet

Younger brains are still forming. Not that that means anything practical. Photograph: Nick Gregory / Alamy/Alamy

Some have pointed to the fact that young people’s brains are still technically developing, so aren’t yet fully mature. Ergo, they shouldn’t be trusted with important, far reaching decisions, which is essentially the whole point of voting. Is this a fair point?

Well, as I’ve reported before, evidence does suggest that our brains are indeed still undergoing development well into our twenties, meaning we’re not “fully mature” until around age 25, not 18 as most age restrictions would imply. And yes, it could be argued that those with “underdeveloped” brains struggle more with impulse control, which I guess you could say suggests a difficulty with long-term sensible thinking.

Except it doesn’t really. You can be massively impulsive all your life, as gambling addicts will know. At least younger people grow out of it. And in any case, “neurological development” is not directly proportional to cognitive maturity. People vary considerably, which becomes obvious when you meet any of them ever, and a “still developing” brain can easily be more capable than a “finished” one, which is why using neuroscience to inform policy around adolescent age limits is far more complicated than many assume.

As well as that, even if we did accept that having a less than a 100% optimal brain was an acceptable reason to disqualify someone from voting, evidence suggests that our brains start to undergo age-related cognitive decline when we hit 30! By the time we reach retirement age, our faculties could be severely compromised. Using this argument, older people definitely shouldn’t vote. I’m sure the Conservatives will be very keen on that.

Young people aren’t experienced enough to make informed choices

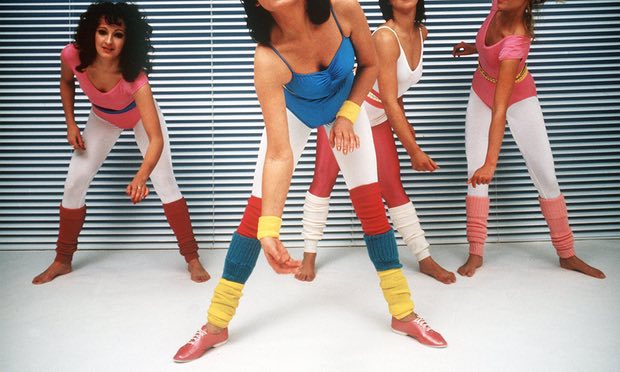

We all make unfortunate decisions when we’re young. But not necessarily because we’re young. Photograph: dpa picture alliance / Alamy Sto/Alamy Stock Photo

How can you really make an informed decision about what government you want when you’re not old enough to have really “experienced” how the world works yet? After all, our life’s experiences are what inform our mental-model, the process via which our brains make predictions and work out how the world operates and influences our behaviour and decisions accordingly. Someone in their early 20s simply doesn’t have enough experience to really make an informed decision about something as important as government.

Again, this argument crumbles as soon as you put it under any measure of scrutiny. Younger people aren’t experienced enough to vote, but they can be trusted to drive, drink, buy a house, have sex and maybe have children and look after them basically forever (although thanks to age limits, they can have sex before they can see sex, because logic), make decisions about their lifelong careers, take on copious debt by going to university, save lives, and much much more. Early 20s is amply experienced to do all of these things, but not vote? Doesn’t stack up.

And anyway, experience doesn’t occur at the same rate for everyone. A twentysomething who grew up on an impoverished estate or was bounced around the country thanks to parents in the military almost certainly has more relevant real-world experience than, I don’t know, say, a 53 year old man from Kent whose daddy got him a job at the stock exchange and who’s had a cushy life amid the upper echelons of society ever since. Surely the latter person is the one who should be kept away from politics altogether? I’d heartily agree.

Students “aren’t from round here”

“This is a local town for local people, there’s no political influence for you here!” Photograph: BBC

One argument against young people voting has focussed on students, who were far more active this election. How is it fair, many have pointed out, for students to swarm into an area during term time, register to vote there, and change the whole electoral dynamic of the older, more established residents?

A valid point, maybe. But only if you assume university is akin to boarding school, which it isn’t. Students, despite the clichés around traffic cones and drinking games, are officially adults, and where they live is officially their home. If they have to pay a TV license, they can vote too. You can’t have it all ways.

In truth, a University is a huge presence in a community, often a vital one, providing jobs, taxes, contributions to infrastructure, a huge customer base for local businesses, many of which are students, who also typically work in local businesses at summertime, often for feeble wages while occupying homes nobody else would put up with.

Basically, this is the anti-immigrant argument in a microcosm. It’s more established (older?) residents saying “You younger, enthusiastic lot; we’ll take your money and your labour that we need to sustain ourselves, but don’t think you’re welcome here or that you can have any rights, those are ours!” I may not be objective as someone who works for a university and with many students, but this stance can, to put it mildly, do one.

Young people are gullible and selfish

You can’t trust young people to vote, they only want free stuff, they are easily fooled. Or so it’s claimed. There’s nothing to really base this claim on; if anything it seems to be projection on behalf of the older, more fortunate generation that enjoyed things like free education and social housing, which are now denied to the younger generation.

But still, it’s not like older people have ever voted based on ridiculous empty promises at everyone else’s expense. Of course not.

*cough*

____________________________________

Dean Burnett is a doctor of neuroscience, but moonlights as a comedy writer and stand-up comedian. He tutors and lectures at Cardiff University. Dean Burnett explains more about our brains in his book The Idiot Brain. Available in the UK, US and many other countries.

Spread the word