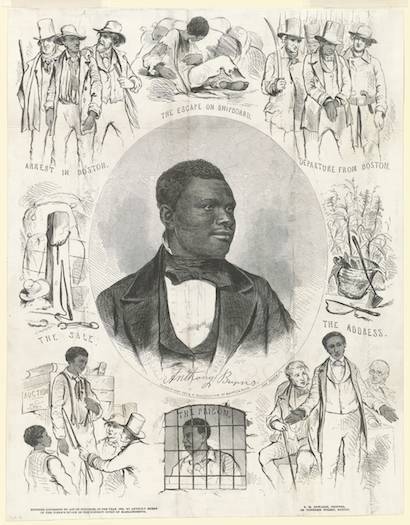

On May 24, 1854, Anthony Burns, a young African-American man, was captured on his way home from work. He had escaped from slavery in Virginia and had made his way to Boston, where he was employed in a men’s clothing store. His owner tracked him down and had him arrested. Under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the United States Constitution, Burns had no rights whatsoever.

To the people of Boston, his capture was an outrage. Seven thousand citizens tried to break him out of jail, and the finest lawyers in Boston tried to make a case for his freedom, all to no avail. On June 2, Burns was escorted to a waiting ship and returned to bondage.

This entire episode had a profound impact on many Bostonians, but one in particular: Amos Adams Lawrence. The Burns episode likely was the first time Lawrence came face-to-face with the evils of slavery, and shortly after Burns was returned to bondage, he wrote to his uncle that “we went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs and waked up stark mad Abolitionists.” (The Whig Party was divided over slavery at this time; by 1854, when the Republican Party was organized, the Whigs were no longer a strong force in U.S. politics.)

A print created in Boston in the 1850s showing Anthony Burns and scenes from his life. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

Lawrence was a somewhat unlikely abolitionist. He was born into one of the bluest of blue-blood families in Boston and had every benefit his family’s wealth could provide, attending Franklin Academy, an elite boarding school, and then Harvard. True, the Lawrence family had a strong philanthropic ethic. Amos’s uncle, Abbott Lawrence, donated $50,000 to Harvard in 1847—which at the time was the largest single donation given to any college in the United States—to establish Lawrence Scientific School, and Amos’s father, also named Amos, retired at age 45 to devote the remainder of his life to philanthropy. In 1854, Amos Adams Lawrence wrote in his private diary that he needed to make enough money in his business practices to support charities that were important to him.

But those business practices made backing an anti-slavery charity unlikely. His family made its fortune in the textile industry, and Lawrence himself created a business niche as a commission merchant selling manufactured textiles produced in New England. Most of the textiles Lawrence and his family produced and sold were made from cotton, which was planted, picked, ginned, baled, and shipped by slaves. This fact presents an interesting conundrum. The Burns episode made Lawrence, as he wrote, “a stark mad abolitionist,” but, as far as we know, the fact that his business relied on the same people he was trying to free did not seem to bother him.

Lawrence very quickly had the opportunity to translate his new-found abolitionism into action. On May 30, 1854, in the midst of the Burns affair, President Franklin Pierce signed into law the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which established Kansas and Nebraska as territories but allowed each to decide for themselves, under the concept of popular sovereignty, whether they wanted slavery or not. To many abolitionists, this was an outrage, because it opened the possibility for another slave state to enter the union. Also, with the slave-holding state of Missouri right next door, the pro-slavery side seemed to have an undue advantage.

This was Lawrence’s chance. A friend introduced him to Eli Thayer, who had just organized the Emigrant Aid Company to encourage antislavery settlers to emigrate to Kansas with the goal of making the territory a free state. Lawrence became the company’s treasurer, and immediately began dipping into his pocket to cover expenses. When the first antislavery pioneers arrived in Kansas, they decided to call their new community “Lawrence,” knowing that without their benefactor’s financial aid, their venture likely would not have been possible.

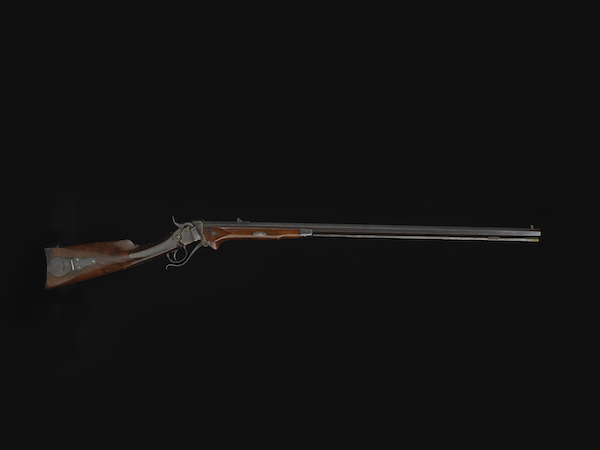

Lawrence was frequently frustrated that the company’s leaders were not aggressive enough to raise money, but he quietly continued to cover the bills. At one point, he confided to his diary, when bills for the Emigrant Aid Company came due, he did not have enough of his own money on hand, so he sold shares in his business to cover the expenses. Whenever there was a need for special funding in Kansas, Lawrence would donate and ask others to do so as well. Lawrence and his brothers, for example, contributed to the purchase of Sharps rifles—the most advanced weapons of the day—for citizens of Lawrence.

44-caliber Sharps percussion sporting rifle used by abolitionist John Brown, ca 1856. Image courtesy of National Museum of American History.

They needed those guns. Because Lawrence, Kansas was the center of the antislavery movement, it became the bullseye of the target of pro-slavery folks. In late 1855, Missourians lined up planning to attack Lawrence in what was called the Wakarusa War. Nothing happened that time, and the Missourians returned home. But less than a year later came the “Sack of Lawrence,” in which pro-slavery Missourians burned much of the town to the ground. Amos Lawrence continued to support the effort to make Kansas a free state. In 1857, Lawrence again dug into his pocket and donated $12,696 to establish a fund “for the advancement of religious and intellectual education of the young in Kansas.”

Eventually, in 1861, Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state. The town of Lawrence played an important role in this development, and several of its residents became leaders in the early state government. But the wounds of the territorial period continued to fester. In August 1863, during the Civil War, Lawrence burned again: Willian Clarke Quantrill, a Confederate guerrilla chieftain, led his cutthroat band into the town, killed more than 200 men and boys, and set the place on fire.

Just several months before, Lawrence had been granted approval from the new state legislature to build the University of Kansas in their town. Citizens needed to raise $15,000 to make this happen, and the raid had nearly wiped out everyone. Again, Amos Lawrence came to the rescue, digging into his pocket for $10,000 to make sure Lawrence, Kansas would become the home of the state university.

In 1884, Amos Lawrence finally visited the town that bore his name. Citizens rolled out the red carpet to honor their namesake. He was honored by the university he was instrumental in creating. He was invited as the guest of honor for several other events. But Lawrence had always been a very private person, and the hoopla over his visit was too much. He stayed for a couple of days, then returned home to Boston. He never visited again.

To the people of modern-day Lawrence, Amos Lawrence has faded from memory. A reporter writing about him in a recent local newspaper article was unaware that he had visited the town. But Lawrence’s support and money were essential in making Kansas a free state. When Lawrence responded to Burns’s brutal treatment, he showed how a citizen can be shocked out of complacency and into action—and thus made history.

_______________________________________________________________

Robert K. Sutton is the former chief historian of the National Park Service. He has written or edited numerous publications on the American Civil War Era, and is the author of Stark Mad Abolitionists: Lawrence, Kansas, and the Battle Over Slavery in the Civil War Era.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.

Spread the word