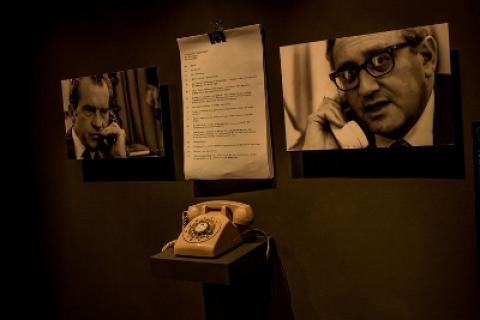

SANTIAGO, Chile - An old rotary phone rings insistently.

Visitors at a new exhibition at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights here in Santiago who pick up the receiver hear two men complain bitterly about the liberal news media "bleating" over the military coup that had toppled Salvador Allende, the Socialist president of Chile, five days earlier.

"Our hand doesn't show on this one, though," one says.

"We didn't do it," the other responds. "I mean, we helped them."

The conversation took place on a Sunday morning in September 1973 between former President Richard M. Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger. The two men were discussing football - and the violent overthrow of a democratically elected government 5,000 miles away with their assistance.

For the exhibition, two Spanish-speaking actors re-enacted the taped phone call based on a declassified transcript.

The chance to listen in on the call is part of "Secrets of State: The Declassified History of the Chilean Dictatorship," an exhibition that offers visitors an immersive experience of Washington's intervention in Chile and its 17-year relationship with the military dictatorship

of Gen. Augusto Pinochet.

An enlarged and dramatically lit document sets the tone at the entrance. It is a presidential daily brief dated Sept. 11, 1973, the day of the coup. Its paragraphs are entirely redacted, every word blacked out.

A dimly lit underground gallery guides visitors through a maze of documents - presidential briefings, intelligence reports, cables and memos - that describe secret operations and intelligence gathering carried out in Chile by the United States from the Nixon years through the Reagan presidency.

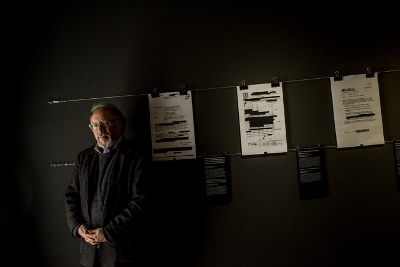

Peter Kornbluh curated the exhibition, which includes redacted documents and C.I.A. memos. "The importance of having these documents in the museum is for the new generations of Chileans to actually see them," he said.

Credit Tomas Munita for The New York Times

"There is an arc of history that is very dramatic when you put these documents together," said Peter Kornbluh, the exhibition's curator who is a senior analyst at the National Security Archive in Washington and director of its Chile Documentation Project. "They have provided revelations and made headlines, they have been used as evidence in human rights prosecutions, and now they are contributing to the verdict of history."

On view are documents revealing secret exchanges about how to prevent Chile's Congress from ratifying the Allende victory in 1970, plans for covert operations to destabilize his government and reports about a Chilean military officer informing the United States government of the coming coup and requesting assistance.

There is a cable from the Central Intelligence Agency to its officers in Santiago after a failed operation in October 1970 to prevent Allende from assuming office, which he did that November. The C.I.A. provided weapons for the plan, which resulted in the killing of the commander in chief of the army, Gen. Ren‚ Schneider, and the agency later sent money to help some of the plotters flee the country.

"The station has done an excellent job of guiding Chileans to a point today where a military solution is at least an option for them," the cable says, commending the officers, even though their plot was foiled.

The exhibition includes only a small sample of the 23,000 documents on Chile that the Clinton administration declassified between 1999 and 2000 in response to international requests for evidence on Pinochet's crimes. The former Chilean dictator was arrested in London in October 1998 and awaited extradition to Spain to face trial on charges of human rights abuses during his rule.

As several other European countries also sought Pinochet’s extradition based on the principle of universal jurisdiction, Mr. Kornbluh, the curator, led a campaign to persuade the White House to release classified records that could serve in an eventual trial against the general.

Documents on Chile from 1968 to 1991 from seven United States government agencies, some of them heavily redacted, were released as part of the State Department’s Chile Declassification Project. Most were declassified months after Pinochet was sent home from London for humanitarian reasons, but just in time to contribute to new judicial investigations in Chile.

The documents have been used as evidence in several human rights inquiries involving American victims, including the 1973 killings in Chile of Frank Teruggi and Charles Horman; the 1976 car bomb assassination of Orlando Letelier, a foreign minister and defense minister in the Allende administration, and his American colleague, Ronni Karpen Moffitt, in Washington; the 1985 disappearance in Chile of Boris Weisfeiler, an American professor; and the killing of Rodrigo Rojas, a Chilean-born United States citizen who was burned alive by soldiers in Chile in 1986.

Copies of the front pages of dozens of newspapers during the Pinochet era, on view in the exhibition.

Credit Tomas Munita for The New York Times

They have also shed light on Operation Condor, a network of South American intelligence services in the 1970s and '80s that shared information, traded prisoners and orchestrated assassinations abroad. The head of DINA, Chile's clandestine intelligence agency, Gen. Manuel Contreras, was the mastermind behind Condor, and hosted an inaugural meeting in November 1975 in Santiago.

In the exhibition, the seats at a rectangular table bear the names of the intelligence chiefs of Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay and Chile who attended Operation Condor's first meeting. A layer of earth covers the table, and brushes are provided for visitors to reveal what is beneath: the names of Condor victims, many of whom vanished without a trace.

Nearby, copies of the front pages of dozens of newspapers from the Pinochet era hang from a panel simulating a kiosk. They were all published by the conservative media empire El Mercurio, which received at least $2 million from the C.I.A.

The records in the exhibition also profile Pinochet, trace intelligence gathering on brutal state-sponsored repression and detail how the Reagan government abandoned Pinochet to his fate in 1988, fearing a further radicalization of the opposition.

"These documents have helped us rewrite Chile's contemporary history," said Francisco Est‚vez, director of the museum. "This exhibit is a victory in the fight against negationism, the efforts to deny and relativize what happened during our dictatorship."

The Memory and Human Rights Museum opened in 2010 during the first term of President Michelle Bachelet and offers a chronological reconstruction of the 17-year Pinochet government through artifacts, recordings, letters, videos, photographs, artwork and other material. About 150,000 people visit the museum annually, a third of them groups of students, Mr. Est‚vez said.

The National Security Archive donated a selection of 3,000 declassified documents to the museum several years ago, while the State Department provided the Chilean government with copies of the entire collection. Chileans, however, have rarely seen them.

"To see on a piece of paper, for example, the president of the United States ordering the C.I.A. to preemptively overthrow a democratically elected president in Chile is stunning," Mr. Kornbluh said. "The importance of having these documents in the museum is for the new generations of Chileans to actually see them."

Spread the word