Firebrand: Journalist Ludwig Lore’s Lifelong Struggle Against Capitalism, Stalinism and the Rise of Nazism

By David Lore

Lulu Publishing, 168 pages

E-book: $8.95

February 1, 2017

ISBN: 9781483459646

Ludwig Lore will be remembered in some quarters today, if at all, as an outstanding defender of Leon Trotsky at the time of the Moscow Trials. Close readers of Theodore Draper’s volumes will find Lore an independent operator of sorts within the left of the 1910s Socialist Party and the 1920s Communist movement—until he was expunged as a renegade and traitor. The saga goes much deeper, and thanks to Lore’s grandson, David Lore, many gaps have become filled, if others are likely to remain forever gappish.

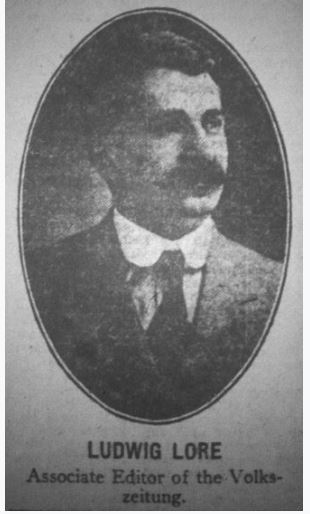

Lore has had particular interest for me as the last of the great editors of the German-American socialist press. Back in the 1870s-90s, it had flourished with long-lasting dailies in New York, Chicago and Milwaukee, dailies and then weeklies in a surprising number of other cities, usually linked to and financially supported by the local trade assemblies. The editors, highly esteemed if not highly paid, often wrote short stories or poetry, lectured and traveled widely as the vaunted intellectuals among proletarian autodidacts. The leading editor who continued on into the 1910s, Hermann Schlueter, also wrote a history of the brewery union and, in English, Lincoln, Labor and Slavery, an extended, thoughtful essay on American life. When Schlueter died in 1919, Ludwig Lore took over as editor of the daily New Yorker Volkszeitung, serving an aging constituency of socialist loyalists.

Building his study on assorted skimpy information, retired newspaperman David Lore has pursued the subject of his grandfather assiduously. Some of the FBI materials dating to the 1920s-30s are still redacted for names (presumably of agents) and will doubtless remain so. What he learned also comes with language limitations: it does not include a reading of the German-language press. Nevertheless, he weaves a fine tale.

“Lore,” he learns to his pain, is not even a family name, just a name chosen to evade the authorities in Germany. A Silesian Jew and socialist youth facing political persecution and the draft in Bismark’s time, Lore chose to travel under a borrowed passport to the US and headed out West in the first years of the new century, toward the rebellious, IWW-leaning hard rock miners of Colorado. And then back toward New York, where he could work as a socialist editor he went, with his German wife, into what an elderly Yiddish interviewee of mine once called the “warm ghetto.”

Lore distinguished himself in the 1910s as a left-socialist, seeking some kind of midway point of possible reconciliation between the Socialist Party and the enthusiasts of the revolutionists across the seas. He was the singular figure in the journal Class Struggle, sharing an editorial berth with Marxist theorist Louis B. Boudin and youngster Louis C. Fraina. As David Lore explains, it didn’t really work out. Most of the leading American followers of Bolshevism disdained left-socialists who were less than absolute devotees of Russian developments. The Communist Labor Party, sympathetic to the IWW and favored by John Reed among others, could not outlast the Communist Party faction, heavily shaded with the ready-for-revolution views of the Russian Federation, and seemingly favored in Moscow.

The Red Scare, pinpointing Lore among others in an indictment by the state of Illinois, might have sent him to jail for a decade. Freed with arguments by no less than Clarence Darrow, he could…go back to work at the Volkszeitung. There, in my own history of interviews, Lore became a jolly middle aged socialist editor, willing to pay his monthly dues to the new Labor Federated Press only when a young Harvey O’Connor (a friend of mine, in Harvey’s own last years) would come by the office or more often Lore’s Brooklyn home for an extended chat, meet his growing children and finally, get a check.

Meanwhile, the space for an independent spot within the Communist milieu shrank to nothing. Lore struggled toward an independent status as the Volkszeitung lost its readers to old age and disillusion. On the way, it became a more interesting, general interest socialistic newspaper with radical culture galore. Then he was replaced in 1931, and thrown once more into earning a living for his family of six. Soon, he would become a columnist for the New York Post (entering its vital, liberal years), an expert on the rise of fascism, and perhaps also, an agent of the Comintern…or not.

This uncertainty occupies a considerable space in Firebrand, no doubt because the available evidence is so ambiguous. Lore found himself at home with German Nazi agents, Comintern agents and others of uncertain status at his door. Ben Gitlow, an erstwhile Communist leader who would become make a career out of his anticommunism, described in The Whole of Their Lives meetings with Lore in his residence, parrot on shoulder, children all around, German food on the table.

Lore had always defended Trotsky personally, without agreeing much on the realistic prospects of Permanent Revolution. His role in the Dewey Commission was notable and the last major political moment of his life. Lore did not live to see the postwar age, with all its fresh contradictions. But David Lore has given us a rich picture of a life.

[Essayist Paul Buhle is a retired senior lecturer from Brown University and the author of numerous works including the two-volume Marxism in the United States and The Artist as Revolutionary, a study of C.L.R James. He has just completed a graphic non-fiction work on Eugene V. Debs, which will be published in 2018.]

Spread the word