After decades of decline unions have found a new champion in efforts to organize workers: the Black Lives Matter movement.

Unions have suffered as manufacturing has moved south away from their old strongholds in the north of the US. Membership rates were 10.7% in 2016, down from 20.1% in 1983, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. At the same time the shift from manufacturing to service industry jobs has hurt them too.

But as the Black Lives Matter and other social justice campaigns increasingly focus on economic justice, unions see a new opportunity. And ironically, a series of defeats for labor in the south is helping to fire up recruitment drives and attracting international support in the process.

Last August’s bitterly fought attempt to unionize Nissan’s plant in Canton, Mississippi is a case in point and one that labor leaders say has made multinationals wary of becoming embroiled in high-profile union-busting drives lead primarily by black workers.

The fight at Nissan, where 80% of the workforce is black, drew international attention as Americans for Prosperity, the rightwing Koch Brothers-backed lobby group, ran ads blasting the United Auto Workers, and the former Democrat presidential hopeful senator Bernie Sanders and the actor and activist Danny Glover descended on the plant to lobby for unionization.

After a narrow defeat, labor leaders charged Nissan not only with illegal anti-union conduct, but with racism. The company denies the charges of racism and illegal anti-union busting. But already labor leaders say they are starting to see a shift and that multinationals, particularly European companies, are concerned about being seen as racist when they move their operations to the South.

“Nissan has been a warning sign on the road. The bad PR, the amount of money that has been lost, the tarnishing of the brand, the sense that they are racially insensitive to the community, no company domestic or foreign wants to be labeled racist,” said Marc Bayard, director of the Black Worker Initiative at the Institute for Policy Studies, who has spent more than two decades attempting to organize multinationals.

“I have had conversations with companies and local Chambers of Commerce, who saw what happened at Nissan and are concerned about being seen as anti-union, anti-community, and racially insensitive,” said Bayard.

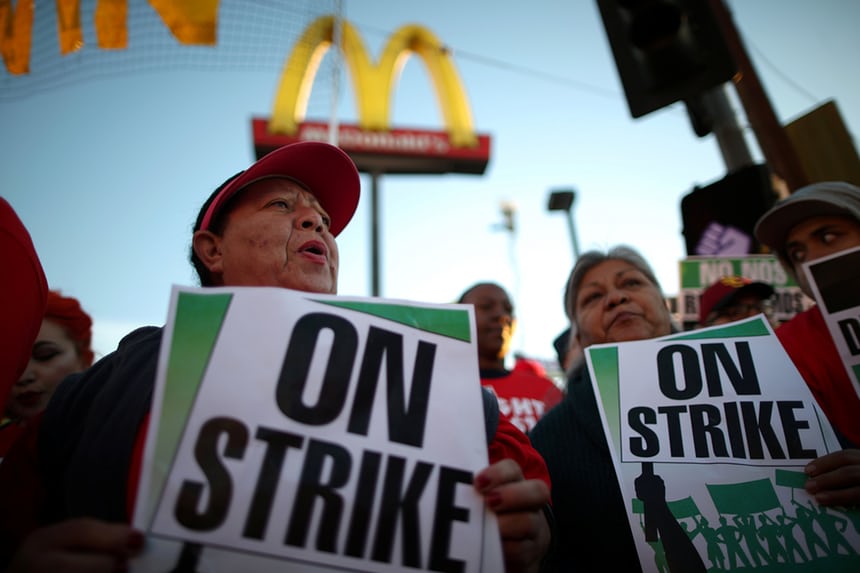

In the meantime, Black Lives Matter is using the voice it has built in social justice campaigns to expand its remit. On 12 February, the Black Lives Matter movement and the low wage workers campaign Fight for $15 are combining for a series of strikes in cities across the US in order to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the Memphis sanitation strike.

The union-backed Fight for $15 has been pushing for more union representation in the fast food industry and has successfully pressed for increases in pay in states across the US but, once again, the southern states have proved harder to crack.

Bernie Sanders at a pro-union rally near Nissan’s Mississippi plant on 4 March 2017. Photograph: Rogelio V. Solis/AP

The fight will not be easy. Labor leaders like Maria Somma, the first Asian American to act as director of organizing for the Steelworkers, says that multinationals go down south to take advantage of racist power structures that make people of color afraid to speak up in the workplace.

“It’s a known fact that African Americans make less than their white counterparts doing their same jobs,” said Somma. “Their work isn’t valued and they know it. This creates a sense of fear because you know the people who are your bosses don’t value you. I believe that employers understand that psychological impact and take advantage of it.”

Somma recently helped lead a union drive of Kumho tire plant in Macon, Georgia, where more than 80% of the workers signed cards indicating they wanted to join the union. But the majority black workforce was again subjected to intense anti-union pressure with daily, hour-long, one-on-one anti-union meetings by a team of seven full-time anti-union consultants for more than two weeks.

The union alleges that Kumho repeatedly threatened to close the plant if workers unionized and to fire workers if they caught them advocating for the union. Kumho defeated the Steelworkers’ organizing attempt by a margin of 164-136and the union alleges that Kumho tried to quash further organizing by firing one of the organizers of the drive, Mario Smith, a mere two days after the vote.

The news of his firing sent chills throughout the plant and attendance at union meetings dropped precipitously.

“It’s hard: nobody wants to hear it right now because nobody wants to get caught scared talking about it,” said Kumho Tire worker Alex Perkins. “They are scared for their job and it’s really hard to get people to talk.”

The United Steelworkers have filed charges with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) against Kumho over Smith’s firing and other alleged abuses.

They have also reached out to their allies in the Korean labor movement to help put pressure on Kumho in Korea.

It is a tactic that has already had some success. In 2015, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) attempted to organize the Swedish manufacturer Electrolux’s brand new 800-person plant in Memphis, Tennessee.

Like Nissan, Electrolux is unionized outside the US, but management in Memphis decided to hire the notorious anti-union law firm Littler Mendelson to run a hardball anti-union drive at the majority African American plant.

Free T-shirts with a slash through the IBEW logo were distributed throughout the plant while TV screens broadcast anti-union messages.

People participate in a Fight for $15 wage protest in Los Angeles, California. Photograph: Lucy Nicholson/Reuters

Supervisors at Electrolux forced workers to attend one-on-one anti-union meetings, where they were grilled about their views on union membership and their work performance. Managers also warned workers that if they unionized, the plant could close. Workers voted against the union by a narrow margin of 57 votes in February of 2015.

After the vote Randall Middleton, the IBEW’s director of manufacturing, flew to Stockholm to meet with IF Metall, the 325,000-strong union that represents Electrolux in Sweden, and brief them on the tactics that had been used to scare workers.

Under pressure from the union, Electrolux reigned in anti-unionization tactics, and workers planning a new vote found support from the Black Lives Matter activists marching in the streets. In July 2016, during the lead up to the election, some workers took part in a protest occupying the Hernando De Soto Bridge over the Mississippi river.

“When they saw us occupying that bridge, they knew that power, and that people in the community had their back,” said Keedran “TNT” Franklin, an organizer with Coalition of Concerned Citizens.

The IBEW subsequently won a landmark victory at Electrolux’s plant by a margin of 461-193.

While such victories are currently the exception to the rule, unions are looking closely at the success of social justice movements. Younger union activists are increasingly focused on not just organizing a campaign based solely on justice for workers, but around race, gender, disability, and sexual orientation, said Somma.

“Young workers get it that you can’t organize without a social justice approach,” said Somma. “I’ve been in the movement for a good number of years and I believe it’s a big change. It’s not coming from union, it’s coming directly from our members and I love it.”

Mike Elk is a member of the Washington-Baltimore NewsGuild. He is the co-founder of Payday Report and was previously senior labor reporter at Politico

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps fund it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as $1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

Spread the word