Birobdizhan, the Jewish Autonomous Region established by Joseph Stalin in the former Soviet Union, is often mythologized and framed with loss or nostalgia; most Jews are gone from the region, and the utopian project of Jewish self-determination there is often viewed as a failure. But the schools still teach Yiddish, and many thousands of people still live there. Should the fact that they’re not Jewish erase them from the history of the region, or indeed from its present? In September 2017, artist and scholar Yevgeniy Fiks visited the Jewish Autonomous Region to see what it is, instead of what it was expected to have been. He shared two essays with us, “Before Birobidzhan” and “Diocese of Birobidzhan”, originally published on his website http://yevgeniyfiks.com.

he discourse on Birobidzhan (the Jewish Autonomous Region of the Soviet Union) consistently revolves around three subjects: utopia, totalitarianism, and the Jews. In the Western press, the most common themes when talking about Soviet-era Birobidzhan are a failed utopian project, Stalin’s plot against the Jews, and a place where Jews don’t live. These negative notions have been also projected on present-day post-Soviet Birobidzhan, which is depicted in Western media as repulsive, laughable, un-Jewish, a failure, and an oxymoron. However, perhaps neither concepts of utopia, totalitarianism, nor Jewishness are relevant today for the discussion of the region in contemporary times circa 2017.

The notion of Jewishness in relation to Birobidzhan appears to be particularly problematic in evaluating the utopian project and the region as it exists today. A Jew has become a unit of measure of the success or failure of Birobidzhan. There are about 2,000 Jews in the region of 200,000. The objectively tiny number is used as an irrefutable proof of the failure of the project of the Jewish Autonomous Region. The fewer the Jews in Birobidzhan the more laughable and oxymoronic Birobidzhan appears for its critics. For these critics, the small population of Jews in the Jewish Autonomous Region (which pales miserably in comparison with the substantial numbers in the state of Israel) clearly indicate that Birobidzhan has been unrealized in practice and defeated in spirit.

However, why are we to measure the success of Birobidzhan by how many Jews live or have lived there? Why is Birobidzhan necessarily about numbers and Jews? Let’s focus our attention on the current population of Birobidzhan. Why do we assume that this non-Jewish majority of Birobidzhan was outside the scope of the Birobidzhan project? Perhaps, they are. And if we accept this population as part of the overall Birobidzhan discourse, then how do we reconcile this living and breathing population with the notion that Birobidzhan has failed? Aren’t people—no matter Jews or Gentiles—are perhaps an irrefutable proof that Birobidzhan succeeded? We must not exclude and ignore these real inhabitants of the contemporary Jewish Autonomous Region from the discourse on Birobidzhan, one that belongs to those who live in Birobidzhan.

Before Birobidzhan

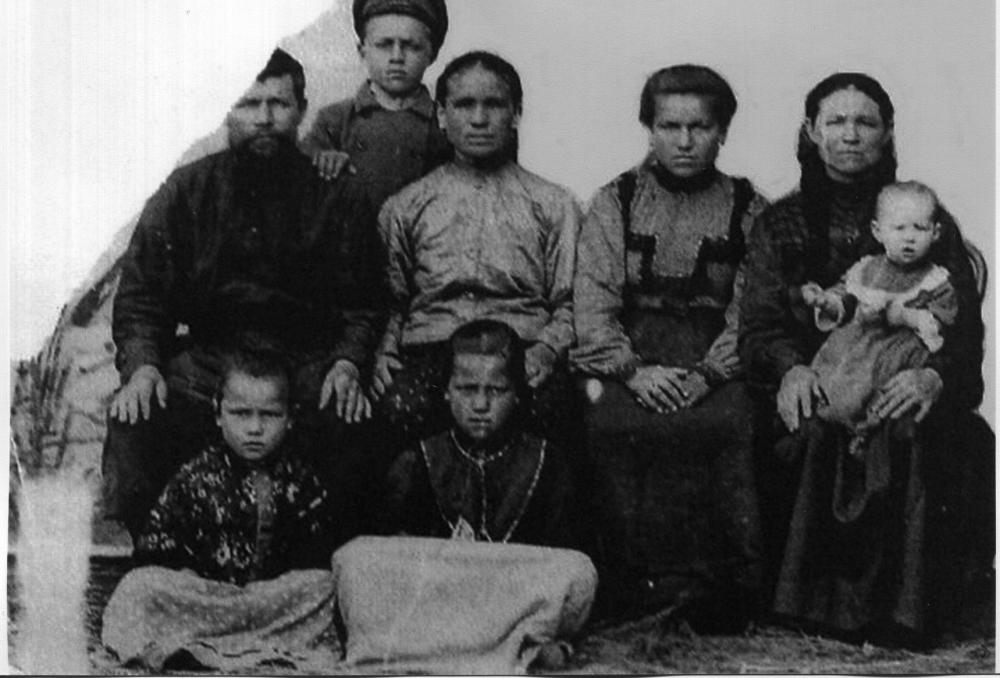

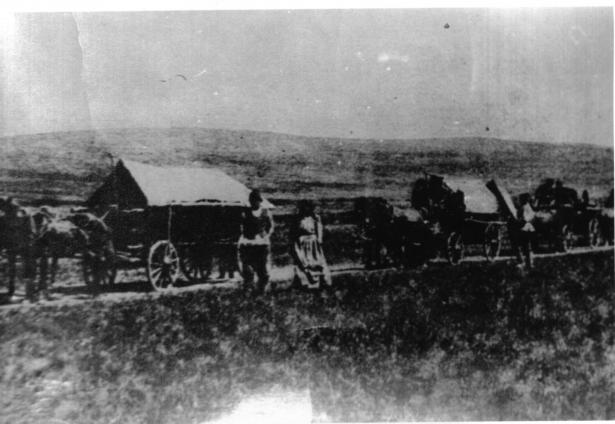

My project “Before Birobidzhan” is about the non-Jewish past of the Jewish Autonomous Region. It elevates the microhistorical narratives of non-Jewish populations who have historically inhabited Birobidzhan before it was established in the late 1920s by the Soviet government. This project bridges the “forgotten” non-Jewish residents of these lands before the creation of Birobidzhan and the “unnoticed” non-Jewish residents of the present-day Jewish Autonomous Region.

“Before Birobidzhan” features photographs of communities and individuals who lived in this area from the 19th century until the late 1920s. This project highlights local histories that in the context of the story of Birobidzhan are usually viewed as “unimportant” or “preliminary” or a point of departure for the real story, which is the Jewish story of “Stalin’s forgotten Zion.” What’s really forgotten about the discourse of Birobidzhan is the local histories “before” this area became a “failed Jewish Utopia.” This project pays due to the unheard voices of the local populations pre-Birobidzhan and attempts to present the Birobidzhan narrative in its totality without compressing this story into a Jewish story (of failure) only. The territory of the contemporary Jewish Autonomous Region was never empty. It wasn’t an uninhabited area as it figures often in the discourse on Birobidzhan.

Where the Jews weren’t

The development of the modern territory of the Jewish Autonomous Region started back in the 17th century. The Russian Cossacks first came here from Siberia in the 1640s. In 1650, a Cossack regiment under the leadership of Yerofey Khabarov made advances in the Amur region, which lead to a military conflict with the Chinese. Although in 1689, the Russia-Chinese Treaty of Nerchinsk was signed, the development of the Amur region was delayed for more than a century and a half.

In 1854, the Governor-General of East Siberia Muraviev-Amurskiy ordered the creation of Russian settlements on the left bank of the Amur river. In 1858, he and Yishan, a representative of the Qing Dynasty, signed the so-called Aigun Treaty, under which the area from the left bank of the Amur to the sea was left to Russia. Under this agreement, Russia received 600,000 square km, which includes territories that are now part of the Chita region, the Sakha Republic, the Khabarovsk Territory, the Amur Region, the Jewish Autonomous Region, and the Magadan Region.

In 1858, two thousand Russian soldiers arrived within today’s Jewish Autonomous Region to cut down forests and clear the areas for Cossack villages. That year, on the left bank of the Amur, eighteen Cossack villages were built. The settlers received from the Russian Government a cash allowance of 15 rubles per family, provision of food, fodder, and seeds for two years and the assistance of the military in the construction of houses. The military sent convoys with weapons and ammunition. To finance the transfer of Cossack families to the Amur, the state treasury spent 1.5 thousand rubles, which at that time was a very large sum. The main means of transportation were rafts and the trip of new settlers took almost a month.

Thousands of pounds of grain were delivered to this region from West Siberia, from the Urals and central Russia. The seed for the agricultural development of the Amur lands by Cossacks, flour, salt, honey, sugar as well as sheep and horses were brought in from the Transbaikalian steppes. The Siberian and Ural plants supplied agricultural equipment including plows and harrows. Arriving on the Amur, 450 families of migrants, and more than 5,500 people began to develop the wildness. Life went on in the heavy work of building villages and plowing the land. The first grains of rye, wheat, barley, and oats fell into the virgin soil.

“We Live Here”

In the fall of 2017, I spent time in Birobidzhan and spoke with people who were born or lived most of their lives there, most of whom weren’t Jewish. This includes spending time with the Editor of the “Birobidzhaner Shtern” newspaper Elena Sarashevskaya. Elena confided in me how she was upset by the constant mentions in the press of Stalin and utopia in reference to Birobidzhan. She felt it was offensive and insensitive towards the present-day residents of the city. Elena said: “Again they are talking about Stalin’s forgotten Zion! Enough already. We live here! What does Stalin have to do with Birobidzhan today? If we are living in a utopia, does it mean that we are living in a nonexistent place?”

I heard Elena. Indeed, how should people residing in today’s Birobizhan feel about their city being called “Utopia” or even worse “failed Utopia”? Are the residents living in a nonexistent place? Yes, Birobidzhan is a provincial, Russian city with a strange connection to Jewish history. But it’s a real place nevertheless. It does exist. The mostly non-Jewish people who were born, lived, and are still living in the Jewish Autonomous Region do not live in Stalin’s forgotten Zion. In fact, they make Birobidzhan real and non-Utopian. Yes, the contemporary Birobidzhan is not the Jewish secular territorial project that dreamers hoped for in the 1930s. But so what?

Elena told me a story about her father who was an industrial worker in Birobidzhan during the Soviet times. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the factory he worked for closed down. Today, that factory reminds him every day of his Soviet life every time he sees the ruins of his factory thru his apartment’s window. This factory was his life. The post-Soviet shock therapy destroyed it and this small, grey, but “okay” Soviet town is disintegrating and the people are fleeing. This is a story of Birobidzhan. This is a real tragedy of Birobidzhan according to Elena. The untold Birobidzhan story is not a “sexy” story about Stalin, Jews, and utopia. The real post-Soviet narrative of Birobidzhan is the post-Soviet collapse of the region’s economy—a free market failure.

Past, Present, Birobidzhan

There is no need to mourn the failure of the Birobidzhan project. Instead, in 2017 we must celebrate its modest but clean streets, at least no apparent poverty, Chinese restaurants, and non-Jewish children learning Yiddish. We must accept the present-day Birobidzhan as an integral part of the larger Birobidzhan narrative and avoid projecting it onto our twentiethth-century ideological nightmares.

“Before Birobidzhan” is a project of both history and potentiality. Birobidzhan is where people were, are, and will be, Jewish or not. If the reality of the Jewish project of Birobidzhan is known to us—it was unsuccessful, half-dead, a laughing stock—then the time of “before Birobidzhan” remains a conceptual space holder of the “what if”. “Before Birobidzhan” remains a time before the future arrives. The discourse of Birobidzhan is about a tension between the possibilities of the then and still the possibilities of the now.

If the “Jews are not there” then who is there? Was/is it still an empty land? No, it was/is not empty. The story of Birobidzhan started before the Jews and continues on with or without them.

Yevgeniy Fiks is a Moscow-born New York-based artist, author, and organizer of art exhibitions.

In geveb, אין געוועב, is a subscription-free digital forum for the publication of peer-reviewed academic articles, the translation and annotation of Yiddish texts, the exchange of pedagogical materials, and a blog of Yiddish cultural life.

Spread the word