Archaeologists have uncovered the earliest evidence of bread-making at a site in northeastern Jordan. Dating back some 14,400 years, the discovery shows that ancient hunter-gatherers were making and eating bread 4,000 years before the Neolithic era and the introduction of agriculture. So much for the “Paleo Diet” actually being a thing.

Bread-making predates agriculture, according to a new study published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. That’s quite the revelation, given the conventional thinking that bread only appeared after the advent of farming. The discovery means that ancient hunter-gatherers were using the wild ancestors of domesticated cereals, such as wild einkorn and club-rush tubers, to make flatbread-like food products. What’s more, the new paper shows that bread had already become an established food staple prior to the Neolithic period and the Agricultural Revolution.

A research team led by Amaia Arranz-Otaegu from the University of Copenhagen analyzed fragments of charred food remains found at a Natufian hunter-gatherer site in northeastern Jordan called Shubayqa 1. The remains of the burnt bread, found in two ancient basalt-stone fireplaces, were radiocarbon dated to 14,400 years ago, give or take a couple of hundred years. This corresponds to the early Natufian period and the Upper Paleolithic era. The Natufian culture lived in the Levant, a region in the Eastern Mediterranean, from around 14,600 to 11,600 years ago.

Prior to this discovery, the oldest known bread came from the 9,500-year-old settlement of Çatalhöyük, located in Anatolia, Turkey. Çatalhöyük dates back to the Neolithic era, a time when ancient humans had already settled in permanent villages and developed farming. The bread found at Shubayqa 1 pre-dates the Çatalhöyük bread by around 5,000 years, and it’s now the oldest example of bread-making in the archaeological record.

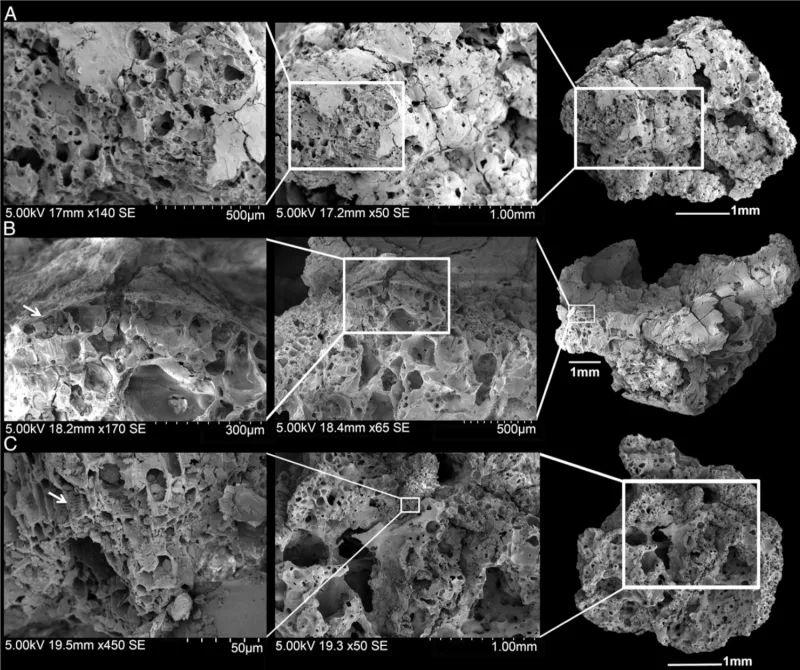

Scanning electron microscope images of bread-like remains from Shubayqa 1. Image: Amaia Arranz-Otaegui et al., 2018

For the study, the researchers analyzed 24 charred fragments of bread from the Shubayqa 1 excavation site using a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). Using SEM, the researchers were able to obtain the high resolution images required for studying the fine structures embedded within the charred materials. These images were compared to experimentally produced bread, allowing the researchers to identify the archaeological specimens. SEM analysis is quite time consuming, and the researchers only managed to analyze 24 fragments out of a total of 600 pieces that appear to be bread or bread-like remains.

Tobias Richter, an associate professor at the University of Copenhagen and a co-author of the new study, said the discovery was surprising on a number of levels.

“First, that bread predates the advent of agriculture and farming—it was always thought that it was the other way round,” Richter told Gizmodo. “Second, that the bread was of high quality, since it was made using quite fine flour. We didn’t expect to find such high-quality flour this early on in human history. Third, the hunter-gatherer bread we have does not only contain flour from wild barley, wheat and oats, but also from tubers, namely tubers from water plants (sedges). The bread was therefore more of a multi-grain-tuber bread, rather than a white loaf.”

Richter said the method used for identifying the bread fragments is new, and that other researchers should use the technique to re-analyze older archaeological collections to search for even earlier examples of bread production.

“I think it’s quite important to recognize that bread is such a hugely important staple in the world today,” said Richter. “That it can now be shown to have started a lot earlier than previously thought is quite intriguing, I think, and may help to explain the huge variety of different types of breads that have evolved in different cultures around the world over the millennia.

Dorian Fuller, an archaeobotanist at the University College London and a co-author of the new study, said it’s highly plausible that hunter-gatherers were able to make bread without the benefit of agriculture.

“Bread at it its most basic is flour, water, and dry heat. The flour should also ideally include some protein, such as gluten, that occurs in wheat to hold the batter together and provide elasticity,” Fuller told Gizmodo. “So this requires a suitable flour, and wild wheats and barleys contain gluten.”

In addition, the necessary equipment to produce flour, like stone tools to pulverize grains, were already in existence by the time this ancient bread was made, as some of the oldest examples date back 25,000 years or more. “So the fact that people would have ground stuff to process it is not surprising,” said Richter. Lastly, the third element to making bread—dry, baking heat—would likely exist in a culture without ceramics, which describes this particular culture at the time.

Ehud Weiss, an archaeobotanist at Bar-Ilan University who wasn’t involved with the new study, says the new paper describes a significant discovery.

“One of the interesting aspects of reconstructing our ancestors’ diet is the technology they used,” Weiss told Gizmodo. “Here, it is clear these people grinded and mixed several types of foodstuff, cereals, and root food to create a baked product.”

Weiss says it’s important to remember that caloric return was a major issue with hunter-gatherers’ diet, especially in challenging environments. Ground and baked foodstuffs have a higher glycemic index (GI) than raw food, where GI is a relative ranking of carbohydrates in foods according to how they affect blood glucose levels.

“Today, we use GI as a tool to avoid food that will add too much sugars to our blood stream,” said Weiss. For hunter-gatherers who struggle in hostile environments to gain more energy from their food, the situation is, of course, the opposite. The ability to increase the caloric return from their food is, therefore, an important step in the development of human nutrition.”

Francesca Balossi Restelli from the Sapienza University of Rome, also not involved with the new study, wasn’t surprised by the finding, saying a discovery of this nature was expected.

“Certainly, finding charred remains of flour products is the much-needed demonstration of what the large quantity of mortars, pestles, and moulders were already showing us,” Restelli told Gizmodo. “If people were cultivating plants, if they had mortars, then they must have been baking ‘bread-like’ foods. The discovery described in the PNAS article is thus certainly extremely meaningful, but not totally unexpected. It is very nice news, as it confirms today’s trend of thought and research.”

University of Cambridge archaeobotanist Martin Jones is excited about the new paper, both for what it tells about about the dietary habits of paleolithic humans, and in the use of a new technique to study the bits and pieces of plant material left behind by ancient humans.

“If we listen to many of the familiar narratives about how humans ate before the advent of agriculture, we hear a great deal about animals, and a bit about seafood,” Jones told Gizmodo. “We have got nowhere near as far with understanding how they worked with plants, and it is beginning to come clear that plant-based cuisine is very old indeed, and very significant.”

“Looking at pulverized plant material is still quite novel,” Jones said. “We archaeobotanists understandably feel more confident about identifying plants before they have been mashed to a pulp. But the SEMs here show how much cellular pattern is still discernible, and how fruitful it can be to persevere and give it a closer look.”

As a final note, this study reminds us, yet again, that the so-called Paleo Diet isn’t an actual thing, or at the very least, not a coherent, unified diet that existed across multiple populations of paleolithic peoples. What’s more, this study doesn’t tell us which particular ancestral diet was the “healthiest,” and it’s doubtful that archaeology can tells us anything meaningful in this regard. When it comes to a balanced, healthy diet, you should listen to the experts: Eat lots of vegetables and fruit, choose whole grains, get your protein, and avoid highly processed foods, especially those with added sugar.

[PNAS]

George Dvorsky is a senior staff reporter at Gizmodo.

Spread the word