What does it mean to be a socialist in America, and why do people get so angry, and angrily terrified, when some Americans espouse socialism as a fairer system than the one in place? These questions have been coming up more frequently in recent years, prompted by the rhetoric and policy propositions of the recent presidential hopeful Senator Bernie Sanders and the ascendance of younger politicians, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the congressional candidate from New York who is unabashedly aligned with the Democratic Socialists of America.

You may find an engaging answer to at least the first of the above questions in “Prairie Trilogy,” a collection of three short documentaries made between 1977 and 1980 and directed by the regional filmmakers John Hanson and Rob Nilsson. Now playing in New York in restored form, the movies are companion pieces to Mr. Hanson and Mr. Nilsson’s 1978 feature “Northern Lights,” a fictionalized tale of the real of the real North Dakota labor union called the Nonpartisan League, which formed about a half a decade before America’s involvement in World War I. The first of the three films is “Prairie Fire,” which uses historical photos and archival footage (shot by Frithjof Holmboe, Mr. Nilsson’s grandfather) to tell the story of a simple struggle in 1916 between the grain farmers of North Dakota and the money men who exploited them.

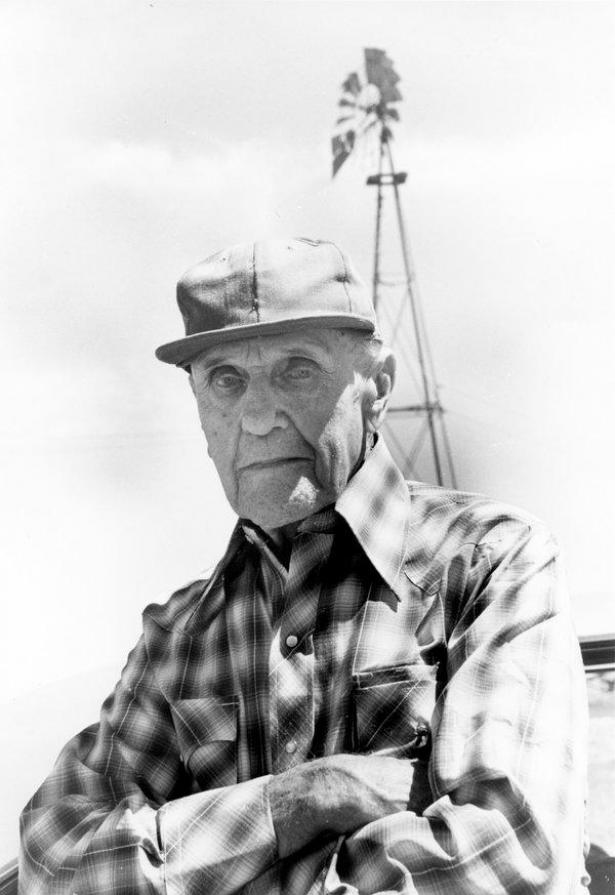

The narrator is Henry Martinson, 97 at the time this movie was assembled, who speaks of the “Eastern grain markets, railroads and banks” that the Nonpartisan League mobilized against. Martinson was an organizer for the League; before that, he had edited a socialist newspaper called The Iconoclast.

The organization had some success in wresting the “mean of production,” as they say, from the moneyed interests who kept at a far remove from the working man. (These money men practiced “hotel politics,” arriving in towns by rail, barricading themselves in deluxe hotels and fixing the local legislatures from there.) Once World War I conscription began, the entrenched media of the day was successfully able to paint the League as anti-American, and it began to fray.

Martinson, who was also a poet, narrates with fervor but also detachment; he’s recounting, not propagandizing. His plain-spokenness about the League’s goals suggests that this socialist’s aim is not some Orwellian nightmare of conformity but a world in which workers are also owners and get what’s coming to them. As opposed, say, to farmers being lent money to buy equipment at such exorbitant rates that they could never pay it back.

The directors use a lot of techniques that would become famous through the work of Ken Burns (whose career was beginning at the time these films were made), such as moving the camera slowly in to a still picture and cutting on movement, to create a feeling of flow within their montages.

The other two films, “Rebel Earth” and “Survivor” (both, like “Prairie Fire,” shot in grainy, immediate-feeling black and white) catch up with Martinson in the then present-day world of the late 1970s. In the company of a younger farmer, Jon Ness, Martinson goes to bars, pool halls and other locales, surveying the situation with grain farmers and in some cases getting into lively arguments. He addresses the North Dakota State Legislature, or at least its empty hall, to the delight of Mr. Ness and his buddies, wryly recollecting the elections he lost.

In “Survivor,” Martinson (who died in 1981 at 98) communes with some of his still-living contemporaries. These are affectionate and affecting portraits. This socialist was a learned man, a little bit of a romantic, but someone nevertheless devoted to practical solutions to very real problems. These films — which were funded, in part, by the North Dakota A.F.L.-C.I.O. — are moving and still pertinent depictions of the human realities that animate labor struggles.

'Prairie Trilogy' will screen in NYC at the Metrograph theater on August 8th at 2:30. Running time: 2 hours. Watch for screenings around the country in select local theaters.

Spread the word