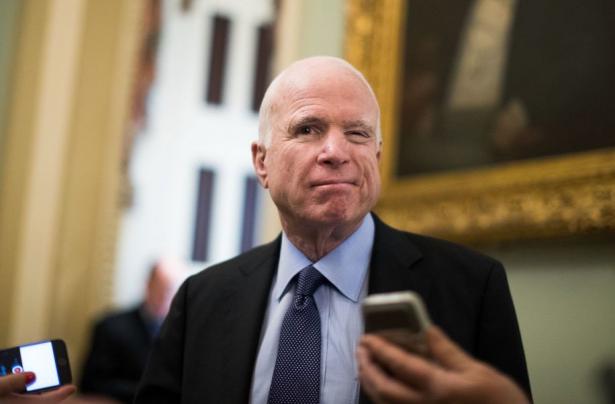

John McCain, the six-term senator from Arizona who succumbed to cancer over the weekend at the age of eighty-one, was less an enigma than a paradox. For every version of McCain that existed, there seemed to be some other, shadow iteration of the man that contradicted, yet somehow coexisted, alongside it.

One John McCain was Trump’s greatest “nemesis”; the other was one of his most reliable congressional allies. One McCain left a legacy eulogized by a prominent socialist as “an unparalleled example of human decency”; the other was known for his vicious temper tantrums and for engineering the wholesale slaughter of millions of civilians. One McCain was a straight-talking “maverick” and principled statesman who was not made for this post-Trump world of craven opportunism; the other was a reliable right-wing Republican who changed his spots as often as he ran a campaign. How could this be?

The story of McCain’s life and career is as much a tale of the obsessions of a media and political culture as it is the story of a man. Fixated on symbolism, rhetoric, war stories, and the concept of bipartisanship for its own sake, the political establishment found a tailor-made idol in McCain, who could deftly feed these compulsions on one hand while dutifully advancing the agenda of the postwar conservative movement of Buckley and Goldwater with the other. In this sense, McCain was one of the most successful politicians of the last forty years, even if his ultimate prize of winning the presidency forever eluded him.

War was in many ways McCain’s birthright, born as he was the grandson and son of admirals, his father serving as the commander of the United States’ Pacific forces during Vietnam. Before that, the senior McCain had led the US invasion of the Dominican Republic to prevent a return to power by supporters of Juan Bosch, the country’s democratically elected reformist leader who had been removed by a coup from taking back power, saying: “People may not love you for being strong when you have to be, but they respect you for it and learn to behave themselves when you are.”

McCain followed his father and grandfather into the military, a decision that would eventually yield four decades’ worth of political capital for the senator-to-be. McCain’s military service would become a staple of his subsequent political mythology. According to a 2008 profile, however, it was largely undistinguished, with McCain frequently crashing the planes he was piloting and, by all accounts (including his own), more interested in partying than taking his training seriously. He graduated at the bottom of a class of 899 people.

While serving as a bomber in Vietnam, McCain was frustrated at the restrictions then imposed by the Johnson administration, calling the civilian commanders “complete idiots.” He was eventually shot down and captured, undergoing years of harrowing torture that left him physically disabled for the rest of his life. McCain’s experience supposedly instilled in him a revulsion to torture, which he would speak out against for the rest of his career, even if his actual record on the issue was less than clear. It also instilled in him a hatred for the Vietnamese, whom he would insist on unapologetically referring to as “gooks” decades later.

McCain would later claim that, while imprisoned, members of the US peace movement visited him, urged him to confess, and, when he refused, told his captors he had to be “straightened out in his thinking.” He would also accuse two of his fellow POWs of being “collaborators” who were “actively aiding the enemy,” because of antiwar statements one of them had made while a POW, a charge that dogged the men for the rest of their lives.

Upon returning from the war, McCain began his involvement in politics, thanks partly to his wife Carol, whom he had relentlessly cheated on while in the Naval Academy, and who was particularly close to the Reagans. When Ronald Reagan launched his primary challenge against Gerald Ford in 1976, McCain lent the celebrity he had achieved as a returned POW to Reagan’s campaign by appearing with him at events.

McCain, who continued cheating on Carol after returning home to find her disfigured from a 1969 car accident, eventually met Cindy Lou Hensley, a much younger heiress to a beer-distributor fortune. He divorced Carol and married Cindy, forever straining his relationship with the Reagans, but giving himself access to the kind of wealth necessary for starting a political career.

McCain moved to Arizona in 1981 and eighteen months later ran for Congress, parrying accusations of carpetbagging by declaring the longest he had lived in one place had been Hanoi. His campaign was partly financed by his father-in-law’s company, and McCain would end up spending $600,000 on the successful race.

As early as 1982, the Washington Post would suggest that the newly elected McCain was not a Reagan backer but a pragmatic, nonideological Republican. He entered Congress as a conventional Reagan conservative, however, backing the president’s supply-side economic policies and a balanced budget amendment, and opposing the Equal Rights Amendment, busing, and the use of federal funds for abortions for poor women.

In 1983, McCain opposed the creation of Martin Luther King Jr Day, a vote he would publicly disavow sixteen years later when he ran for president the first time. It began what could charitably be described as a complicated relationship with black people in the United States.

While McCain ultimately worked to create a state version of the holiday (though not before supporting the Arizona governor’s repeal of the state’s recognition of King) and reportedly forged connections with a handful of high-profile local black leaders in Arizona, the state’s black community by most accounts rarely saw or heard from him. In 1990, he was a crucial vote allowing George H. W. Bush to become the first sitting president to veto a civil rights measure, the Civil Rights Act of 1990. Until his dying day, he would receive consistently dire ratings from the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a fact belied by its president’s praise for McCain upon his death.

Even so, McCain would go on to forge a career as a Republican rebel, a career trajectory nearly derailed by the Keating Five scandal. McCain, who had intervened with federal regulators on behalf of Charles Keating, a developer with whom he had years of personal and financial connection to, was ultimately decided to have acted with “poor judgment” in the matter, and never charged.

McCain established his “maverick” status early in his career on the back of a handful of deviations from Republican orthodoxy. He was praised for voting with environmentalists on some issues, working on “Indian affairs,” backing sanctions against apartheid South Africa, and voicing his intent to appeal to minority voters, describing himself as “sensitive” to the concerns of non-whites. His attempts to regulate tobacco and opposition to ethanol subsidies have also been cited, and to his credit, McCain pushed for a diplomatic opening to Vietnam through the 1980s and 1990s.

But the issue that by far loomed the largest in creating this image was campaign finance reform, which McCain pursued sincerely throughout the 1990s and 2000s. One of the earliest instances of the word “maverick” being applied to McCain came in this 1993 Washington Post piece, in the context of his pursuit of the reform. Such portrayals often came alongside portraits of a pensive McCain ruminating on military service and his debt to the US armed forces.

McCain solidified this image with his 2000 campaign, which struck a somewhat populist note by stressing campaign finance reform, denouncing lobbyists, calling for the closing of corporate tax loopholes, and attacking Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson as “agents of intolerance.” One of two Republicans to vote against Bush’s tax cuts for the rich, John Kerry asked him to be his running mate and various Democrats coveting the sheen of bipartisanship bragged about working with him. By the time he ran for president in 2008, his overuse of the term “maverick” practically became a joke.

Much of this was due to the friendly rapport that McCain, who could be genuinely affable and funny, built up with journalists and others. His status as liberals’ favorite Republican was solidified by his frequent appearances on the Daily Show where he traded jokes with Jon Stewart. It was a self-conscious brand.

Keen observers noted, as the Toronto Globe and Mail did in 2008, that McCain was really “a hard-line Republican with a few points of divergence from the party’s mainstream.” As of 2017, McCain has a 81 percent lifetime rating from the American Conservative Union. He receives consistently high scores from the Campaign for Working Families, a free market, traditionalist political action committee, including four 100-percent ratings since 2009. And despite his reputation as a squeaky-clean reformer, McCain preceded his 2000 campaign by directing a telecom lobbyist who made a habit of touting her access to him to conveniently disappear.

Despite his condemnation of Falwell and Robertson — motivated at least in part by their attacks on him in the 2000 primaries — McCain long found cause with the religious right. Fundamentalist lobby group Christian Voice gave McCain a score of 92 percent in 1987, its highest at the time. McCain privately assured Gary Bauer, head of the Family Research Council (defined as a homophobic hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center), that unlike Bush he would appoint pro-life judges as president, winning his endorsement in both 2000 and 2008.

Like the fundamentalists he supposedly despised, McCain wanted Roe v. Wade overturned, with abortion illegal with only a few exceptions. He received consistently dreadful scores from pro-choice organizations, while from 2009 until his death he received 100-percent scores from the National Right to Life Committee every year. When it was time to run for president again, he swiftly re-embraced Jerry Falwell and started putting air quotes around women’s “health” in the context of abortion.

These apparent about-faces were part of a broader decision by McCain to parachute visibly into the sphere of the conventional right, seen in his embrace — literally — of once-rival George W. Bush, and his sudden calls for making his high-earner tax cuts permanent. They shocked media figures and others who thought of McCain as a beloved, principled, and politically idiosyncratic figure.

In truth, they hadn’t been paying attention. Even in 2000, when McCain had first been credulously treated as a “maverick,” he played the game of courting Democrats in some states while bashing Bush as too liberal in others. Campaigning in South Carolina, he called the Confederate flag a “symbol of racism and slavery,” then the next day labelled it a “symbol of heritage,” later admitting to lying for fear of political backlash.

McCain was prone to such political camouflage because he was motivated largely by naked ambition, as he explained in his remarkably honest 2002 memoir. “I have craved distinction in my life,” he wrote. “I have wanted renown and influence for their own sake.” He went on:

I didn’t decide to run for president to start a national crusade for the political reforms I believed in or to run a campaign as if it were some grand act of patriotism. In truth, I wanted to become president because it had become my ambition to be president. I was 62 years old when I made the decision, and I thought it was my one shot at the prize.

McCain’s thirst for “renown and influence” led him to what may well be the lowest moment of his career. The prospect of the presidency slipping from his grasp in 2008, he embarked on one of the more racist campaigns in modern memory, launching scurrilous personal attacks on Obama in speeches and television ads, and winking at far-right conspiracy theories about the Democratic nominee. In the process, he riled up the kind of frightening, racialized hatred that prefigured Trump’s run eight years later, leading to a spike in death threats against Obama.

Due to a combination of bitterness at losing the election and concern for losing his seat, McCain made a further rightward shift after his defeat. He became an implacable foe of Obama, joining his fellow Republicans in their successful campaign to obstruct the new president’s agenda at all costs, and leading the charge against both health care reform and the stimulus that helped prevent another Great Depression. Liberal journalists noted that on issues ranging from climate change to campaign finance reform, to LGBT service in the military, McCain abandoned his former positions, and media figures wondered what had happened to the man they once considered a hero.

His standing in the liberal and centrist establishment would be revived by Trump’s petty insults toward him, which elicited fervent defenses of the senator and his record. Since 2015, McCain has been an unceasing critic of Trump, verbally assailing the president on a regular basis, and in the process rehabilitating his standing among the liberals and centrists who only a mere few years earlier had been disillusioned with him. Like a face turn in pro wrestling, the disquieting parts of McCain’s history were not so much erased as abruptly forgotten and ignored.

McCain, on the other hand, cannily used his criticisms of Trump to mask his steadfast support for the president’s agenda, his actions now consistently buried under a blanket of media coverage painting him as preternaturally honorable, decent, and bipartisan.

Meanwhile, McCain publicly pledged to block any Supreme Court pick either Obama or Clinton chose and voted for 83 percent of Trump’s agenda, defying him on issues like raising the debt ceiling to grant hurricane relief and imposing sanctions on geopolitical foes. So seductive has the mythology built up around McCain been that even the journalists who created this metric have tied themselves in knots to explain the importance of McCain’s contradictory rhetoric.

This reached its apogee with the surreal spectacle of mainstream media lionizing a brain cancer-stricken McCain’s return from his taxpayer-funded hospital stay to both admonish his party over its Obamacare repeal bill, while voting twice to advance that very same bill. McCain, who had staked his political reputation over the past nine years on promising to strip millions of their health care, surprisingly voted against the “skinny repeal” bill in the end, reportedly because he couldn’t get assurances for a wider repeal of the law. Then he voted for the GOP’s cartoonishly plutocratic tax bill, which itself decimated Obamacare, while allowing McCain’s children to receive a $22 million tax-free inheritance.

As his very final act, McCain, despite being absent from the Senate since last December — and despite 62 percent of GOP voters believing he should resign to allow a replacement to be elected — refused to leave his seat, ensuring that it would be filled by a Republican appointee who will serve through 2020. The decision means Trump’s Supreme Court pick, whom McCain supports, will likely be confirmed, and that Trump and the GOP will have another ally in Congress until the next presidential election.

It was a fitting end to McCain’s career. On the edge of death, McCain executed a cunningly partisan maneuver, handing Trump a major victory that will help stifle future progressive legislation and potentially immunize the president from investigation, all while headlines blare about the two men’s antipathy for each other.

One part of McCain’s legacy deserves special attention: his foreign policy.

It’s a fitting coincidence that the term most associated with McCain — “maverick” — is also the name of an air-to-surface missile that was first deployed in Vietnam and has since been used in both wars against Iraq. Besides his quiet support for Trump, McCain’s longest lasting legacy will be the civilians he’s killed, the countries he’s destroyed, and the regions he’s destabilized through his bellicose foreign policy.

McCain didn’t start out his political career as a hawk. Using his harrowing wartime experience as justification, McCain was an opponent of military intervention early on, opposing Reagan’s ongoing troop deployment in Lebanon in 1983, criticizing his spiraling defense budgets, and urging him to push for arms control with the Soviet Union. He opposed Bill Clinton’s intervention in Haiti and tried to force him to withdraw troops from Somalia, arguing that “the longer we stay the more difficult it will be to leave,” and that the loss of US lives there was “tragic” and “needless.”

McCain was more a realist than an anti-interventionist; his support for foreign adventures was always tied to his conception of US interests and the possibility of success. So after warning Bush against military intervention in Panama, he backed Noriega’s 1989 ouster by force. He made noises about wanting to keep the US out of Iraq the first Gulf War, but eventually supported it, declaring that “if we fail to act that there will be inevitably a succession of dictators, of Saddam Husseins.”

Throughout the 1980s, McCain was also a steadfast supporter of the Nicaraguan Contras, the paramilitary forces known for cutting a swath of murder, torture, and rape in Central America. When Congress cut off aid to the Contras (a move McCain said would be viewed “as a low point in United States history” by historians), he donated $400 of his own money to charitable foundations that had been set up to funnel money to the death squads.

At the time, McCain was serving on the advisory board of a group created by the World Anti-Communist League, a pro-Contra organization whose Latin American affiliate was fervently antisemitic and supported pro-Nazi groups. The group served as a public front for the illegal supply of aid to the Contras.

It was in the 1990s, with the Cold War over and after interventions in the Gulf and Yugoslavia (the latter of which he also supported), that McCain moved in earnest to the neoconservative right. He served as president of the Bill Kristol-founded New Citizenship Project, the parent organization of the Project for the New American Century (PNAC), and began pushing for war with Iraq in the late 1990. Only a month after September 11, he suggested Iraq was linked to the spate of anthrax attacks that had hit the US. Prominent neocons from the PNAC joined his presidential campaign.

McCain’s promotion of US meddling in other countries extended past military involvement. Since 1993, McCain served as the chairman of the International Republican Institute, a corporate-funded, quasi-governmental organization that meddled in other countries’ politics to push free-market reforms. In the 1990s, it helped to swing elections in Mongolia and Russia, with disastrous consequences for their citizens. Besides engaging in the kind of election meddling McCain has more recently called an “act of war,” the organization doubled as an influence-peddling vehicle for lobbyists and business executives to curry favor with McCain.

Since his shift to something approaching neoconservatism, McCain has supported just about every military conflict that’s come his way, including Afghanistan and the disastrous war in Libya. The latter not only established open-air slave markets in the country, but exacerbated the current migrant crisis, and destabilized the region by allowing a flood of arms to extremists in Syria, Mali, and the Tunisian border.

Besides joking about bombing Iran, McCain seriously advocated force to stop it from acquiring nuclear arms, and suggested Israel should “go rogue” to undercut Obama’s Iran deal. He pushed for airstrikes against North Korea, temporarily joined forces with Obama to call for a strike on Syria, and sent weapons to Saudi Arabia for its war in Yemen, an unspeakable humanitarian disaster. Meanwhile, he compared Obama to Neville Chamberlain for shaking hands with Raul Castro.

Trump’s election afforded McCain a significant victory on foreign policy. McCain’s criticism of Trump was almost exclusively devoted to the latter’s foreign policy rhetoric, which he viewed as insufficiently hawkish on Russia, a continuation of the same criticisms McCain had spent years making about the Obama administration. Yet even as McCain excoriated Trump publicly, his administration at last permitted the sale of weapons to Ukraine, a policy McCain had spent years unsuccessfully pushing for under Obama.

Just as McCain’s support of anti-communist forces in the 1980s put him in league with pro-Nazi forces, however, so did his support for Ukraine in the last years of his life. McCain has stood shoulder to shoulder multiple times with antisemitic neo-fascists as part of his support for an anti-Putin bulwark in Ukraine, and there’s evidence that some US weapons have made their way into the hands of far-right forces.

It’s too soon to say just how the Ukraine policy McCain pushed for until his dying day will turn out. But depending on how things develop, his foreign policy legacy could well end up even darker than it already is.

The Greatest Trick

John McCain was a relatively conventional conservative politician whose greatest accomplishment was convincing the public that he was anything but.

Armed with a self-effacing wit and a potent, patriotism-inducing life story, McCain survived nearly four decades in the beating heart of American power by charming a media and political culture perpetually on the lookout for a reasonable, moderate right. In his twilight years, he was one of the first politicians to realize the power of rhetorically condemning Trump, and used it to both successfully push his traditional concerns — namely, a hyper-aggressive foreign policy and free market economics — and to enact Trump’s agenda without having his legacy tarred by the president’s unpopularity.

McCain undeniably had a constructive side, including his push for campaign finance reform. But any victories he won in that vein have tended to be undone by the conservative movement whose goals McCain faithfully backed throughout his decades in power. Meanwhile, his support for Trump’s agenda, coupled with his shrewd and likely successful effort to ensure a hard-right majority on the Supreme Court, is a virtual death sentence for any of the moderately progressive causes McCain claimed to champion. If they are saved, it won’t be due to McCain’s speeches, but because of a mass movement comprised of the ordinary Americans disproportionately hurt by the policies McCain pushed while in office.

Perhaps McCain’s greatest victory is that he died having achieved the “renown and influence” he had always craved. After his scurrilous presidential campaign rhetoric and Obama-era obstructionism dented his public standing, he rehabilitated his image, and died lavishly feted by the media class that had once rejected him, all while changing nothing about his politics — if anything, moving further toward the edges of the extreme right. What a crock.

Spread the word