Now, we know.

When 19 sticks of dynamite planted by Klansmen exploded inside the 16th Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963, killing 11-year old Carol Denise McNair, and 14-year-olds Cynthia Wesley, Addie Mae Collins and Carole Robertson, it was not the first time white supremacists had bombed a home or place of worship in Birmingham, Ala. It was not the second. It was not the 10th, nor was it the 40th. It would also not be the last.

Although the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing is the most famous of these, it was not a lone incident. Bethel Baptist was bombed three times. Explosives were planted at the home of Rev. A. D. King twice in two years, including 50 sticks of dynamite in 1965. Between 1947 and 1965, homes, gathering places and churches in Birmingham, Ala., would be bombed 50 times.

But on that September day in 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was about to step into the pulpit at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta when someone delivered the news. King first contacted President John Kennedy and promised to appeal for peace. But of all the people on the entire planet, King wanted to have a word with one particular man. King did not blame God or Satan for this tragedy because he knew who was responsible. So he sat down, dictated a telegraph and sent it to that man, saying, in part:

...he blood of four little children ... is on your hands. Your irresponsible and misguided actions have created in Birmingham and Alabama the atmosphere that has induced continued violence and now murder.

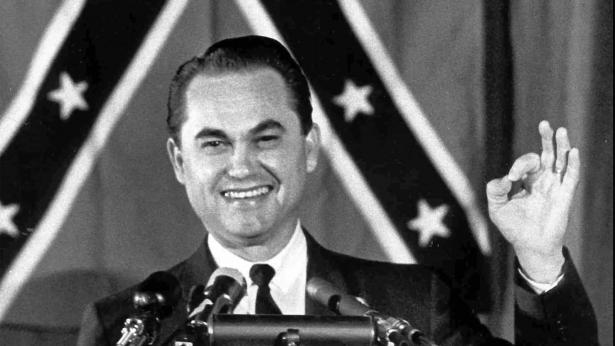

Then he sent that telegram to the honorable governor of the great state of Alabama, Mr. George Wallace.

Aside from his spelling and ability to speak in complete sentences, George Wallace was a lot like Donald Trump. His racist rhetoric fueled his constituents. His presidential campaign slogan “Stand Up for America” was the 1968 version of “Make America Great Again.” He told followers at his rallies to attack people and had protesters dragged out of his rallies. He claimed he was standing up for his base and white resentment.

But most of all, he invoked hate and racism. After a failed bid for governor in 1958, he claimed he lost because he wasn’t racist enough and vowed to never be “out-niggered” again. In 1962, Wallace ran again as the staunchest segregationist in the country and harnessed white supremacy as his platform.

When a supporter asked why he started using racism as a political tool, Wallace replied, “You know, I tried to talk about good roads and good schools and all these things that have been part of my career and nobody listened. And then I began talking about niggers, and they stomped the floor.”

And at his inauguration in 1963, after his racist invocations made him the most powerful man in the state of Alabama—much like Trump did with his white nationalist speech to the joint session of Congress shortly after his 2016 election—Wallace told the adoring crowd in his infamous “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” speech:

As the national racism of Hitler’s Germany persecuted a national minority to the whim of a national majority . . . so the international racism of the liberals seek to persecute the international white minority to the whim of the international colored majority...

But we warn those, of any group, who would follow the false doctrine of communistic amalgamation that we will not surrender our system of government . . . our freedom of race and religion . . . that freedom was won at a hard price and if it requires a hard price to retain it . . . we are able . . . and quite willing to pay it.

Doesn’t it sound familiar?

And many of those previously mentioned bombings, including the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, were carried out by a man named Robert “Dynamite Bob” Chambliss, one of the most notorious terrorists in American history. Chambliss had risen to the title of the “Exalted Cyclops” in the Ku Klux Klan. He eventually became friends with some of the most notorious racists in Alabama including Birmingham’s Bull Connor, who hired Chambliss as a city mechanic and protected him during his “one-man war” against integration.

What supposedly inspired the 16th Street Baptist bombing was George Wallace standing at the entrance of the University of Alabama to try to stop federal troops from forcing the school to integrate. The FBI’s informant says the integration of Alabama combined with the desegregation of Birmingham schools sent Chambliss “over the edge.”

But was this necessarily Wallace’s fault? Should political rhetoric be blamed for this heinous act of violence?

To say that, you’d have to prove the words were meant to incite violence. You’d have to prove that Wallace’s words were an intentional provocation by someone who knew exactly what they were doing. Maybe it isn’t George Wallace’s fault because, to him, they were just words.

In fact, those words weren’t even written by Wallace. They were written by Wallace’s speechwriter, Asa Carter (whose story may be the most fascinating one you’ve ever heard, by the way). Asa had a gift for words and became Wallace’s speechwriter after he changed his trajectory in life when he was charged with attempted murder during a shootout at one of his hangouts where he was a leader for...

The Alabama headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan

A Klansman’s words resonated with a Klansman killer. They may not have caused those bombings, but they were kerosine on an already lit fire. George Wallace might not have been personally responsible for the political violence of his day, but he at least played a small part, according to many people.

And words matter. They can inspire violence as much as they can inspire hope. Trust me, I know. Dr. King knew. Yet, in spite of the recent acts of political terror, we have learned one valuable lesson:

When Donald Trump repeats his infamous slogan, you should think of the city called “Bombingham.” You should think of the one neighborhood in Birmingham that is still called “Dynamite Hill,” which was bombed more than most war-torn countries. And you should think of the 50 separate times between 1947 and 1965 that dynamite was planted in that city

Because that is obviously the “again” part of “Make America Great Again” on the hat that makes Kanye feel like a superhero.

Now, we know.

Spread the word