Sure, Democrats are lining up behind Medicare-for-all. But what exactly does that mean?

This year, dozens of Democratic candidates ran — and won — on a promise to fight to give all Americans access to government-run health care. A new Medicare-for-all Caucus in the House already has 77 members. All the likely 2020 Democratic nominees support the idea, too.

“Medicare-for-all” has become a rallying cry on the left, but the term doesn’t capture the full scope of options Democrats are considering to insure all (or at least a lot more) Americans. Case in point: There are half a dozen proposals in Congress that envision very different health care systems.

“Democrats ran on health care,” says Hawaii Sen. Brian Schatz. “We now control one chamber of Congress. We have an opportunity and an obligation to demonstrate what we’d do if we were in charge of both chambers. We have an obligation to hear from experts and figure out the best path forward.”

We spent the past month reading through the congressional plans to expand Medicare (and a few to expand Medicaid, too) as well as proposals at major think tanks that are influential in liberal policymaking. We talked to the legislators and congressional staff who wrote those plans, as well as the policy experts who have analyzed them.

These plans are the universe of ideas that Democrats will draw from as they flesh out their vision for the future of American health care. While the party doesn’t agree on one plan now, they do have plenty of options to choose from — and many decisions to make.

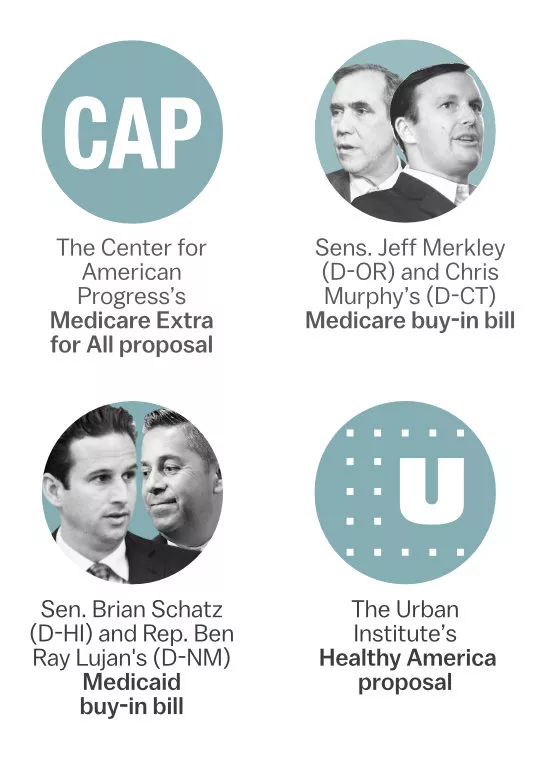

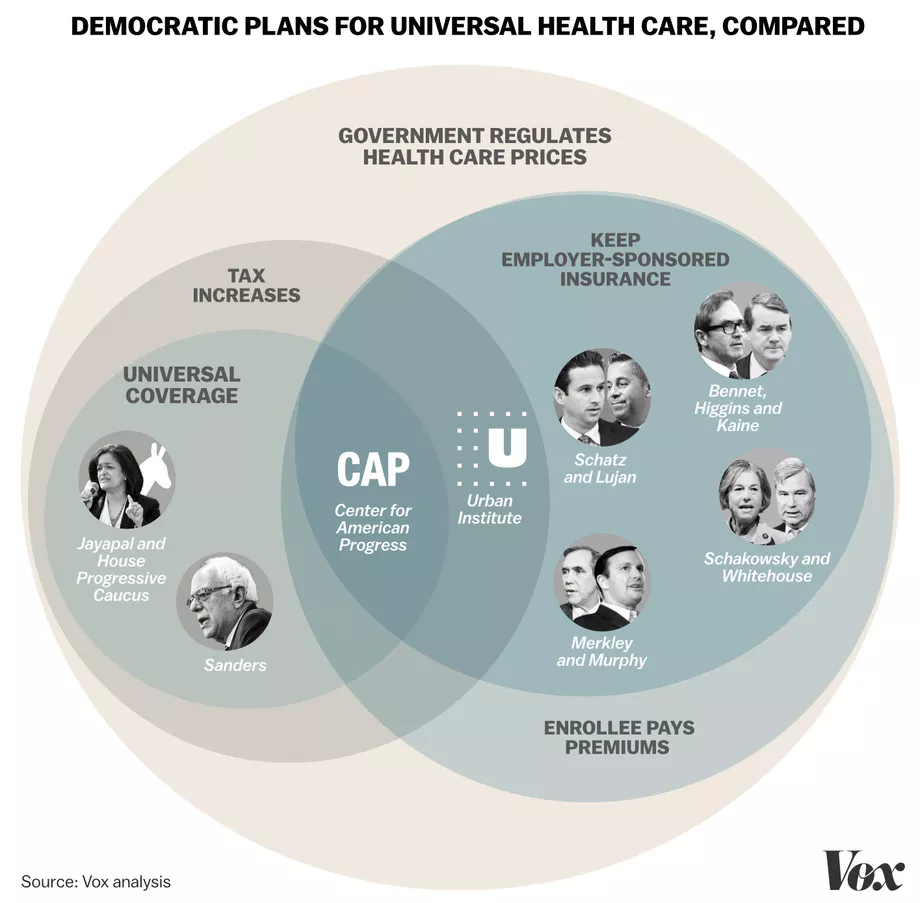

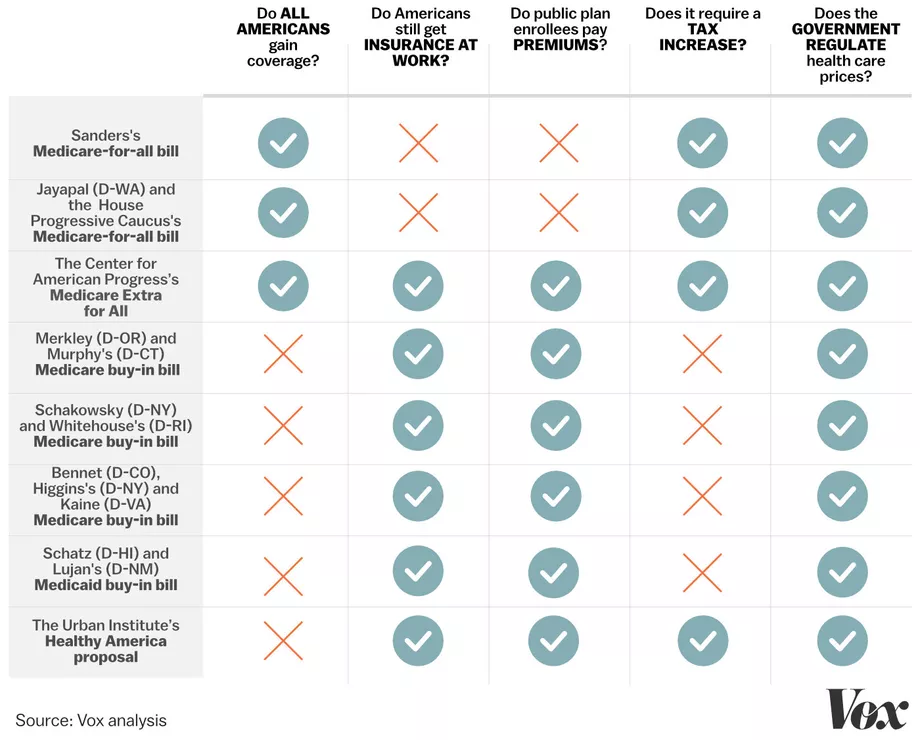

The eight plans fall into two categories. There are three that would eliminate private insurance and cover all Americans through the government. Then there are five that would allow all Americans to buy into government insurance (like Medicare or Medicaid) if they wanted to, or continue to buy private insurance.

The bills we reviewed are:

We learned these plans are similar in that they envision more Americans enrolling in public health plans. They would all give the government a greater role in everything from setting health prices to deciding what benefits get included in an insurance plan. Experts say all these bills would almost certainly create an insurance system that does better to serve Americans with high health care costs.

“If you’re really sick and have high drug costs, it would be hard not to benefit from these bills,” says Karen Pollitz, a senior fellow at the Kaiser Family Foundation who recently co-authored a report comparing the different Democratic plans to expand public coverage.

But the Democrats’ plans differ significantly in how they handle important decisions, like which public health program to expand and how aggressively to extend the reach of government. Some would completely eliminate private health insurance, eventually moving all Americans to government-run coverage, whereas others still see a role for companies providing coverage to workers.

Some bills require significant tax increases to pay for the expansion of benefits — while others ask those signing up for government insurance to pay the costs.

And while Democrats aren’t under any illusion that they’ll pass Medicare-for-all this Congress, they see the next two years as key to figuring out where consensus in the party lies. More plans are coming too: Jacob Hacker of Yale University, for example, has outlined the contours of a plan called Medicare Part E, and House legislation is in the works to flesh out the details.

“We want to have public hearings on this, we want to see movement on the issue,” says one Democratic House aide working on this legislation. “The Senate is still Republican but right now, Democrats have the opportunity to build support, have public hearings, and help move this idea along and educate members.”

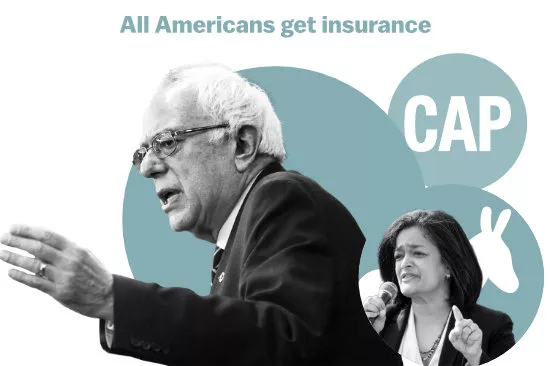

How many people get covered?

Bottom line: Some plans from the Democrats would cover all Americans — while others would provide insurance to more but leave some number of people uninsured.

In a way, this is the fundamental question. Even under the Affordable Care Act, 30 million Americans don’t have health insurance. The left believes health care is a human right, and mainstream Democrats aren’t far behind them. The whole reason Democrats are ready to take up health care reform again so soon after the ACA is to fix this problem.

Medicare-for-all (Senate and House): Every single American would be covered by a government insurance plan, after a short phase-in period.

Medicare and Medicaid buy-ins (congressional plans): Millions more Americans would likely be covered, but experts don’t expect the various buy-in plans to achieve universal coverage. They would still, after all, be optional programs.

Medicare Extra for All (Center for American Progress): The health care plan from the leading Democratic think tank would achieve universal coverage for all legal residents, through a combination of private and public insurance — at least for the next few decades. It eventually foresees getting to a very similar level of coverage as the Medicare-for-all proposals in Congress, by enrolling all newborns into a government health plan and taking steps that would diminish the role of employer-sponsored coverage.

Healthy America (Urban Institute’s Linda Blumberg, John Holahan, and Stephen Zuckerman): This center-left plan from three Urban Institute fellows is explicitly not a plan for universal coverage, by attempting to work within certain political constraints. But it would, according to Urban’s estimates, cut the number of uninsured by 16 million in its first year.

A big part of the remaining uninsured would be undocumented immigrants. The plan’s authors said the program could be adjusted to cover that population but didn’t think there’d be political will to do so.

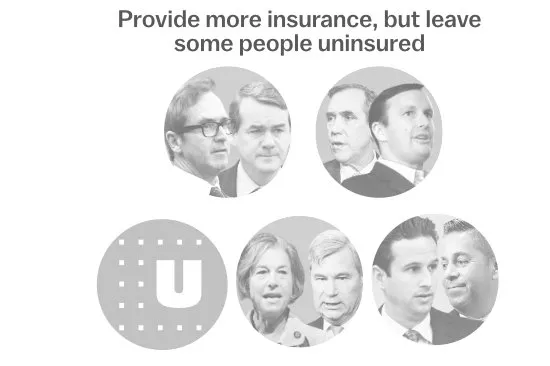

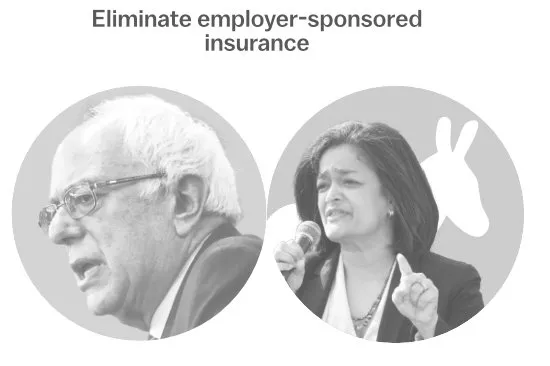

What happens to employer-sponsored insurance?

Bottom line: Democrats are split over whether expanded Medicare should make space for employer-sponsored plans — or get rid of them completely.

Nearly half of all Americans get their insurance at work — and Democrats’ various health care plans make different decisions about whether that would continue.

Currently, the American health care system provides employers with a big incentive to provide coverage: Those benefits are completely tax-free. This means companies’ dollars stretch further when they buy workers’ health benefits than when they pay workers’ wages.

This, however, creates an uneven playing field. Fortune 500 companies get, in effect, a huge federal subsidy to insure their workers, while an individual who doesn’t get coverage through their job and makes too much money to receive subsidies under the Affordable Care Act doesn’t get any advantageous treatment under the tax code.

Medicare-for-all (Senate and House): Both the Medicare-for-all plans would make the biggest change and eliminate employer-sponsored coverage completely. Under these options, all Americans who currently get insurance at work would transition to one big government health care plan.

Medicare/Medicaid buy-ins

The question of work-based insurance is prickliest for the Medicare buy-in plans. Broadly speaking, under those bills, more Americans would be allowed to purchase a public insurance plan under the Medicare umbrella. Everybody who currently buys insurance on the individual market would be allowed to buy a Medicare plan, under each of the buy-in bills.

But they differ in important ways in how much they would let people leave their current job-based insurance for the new government plan.

The “Choose Medicare” Act (Merkley and Murphy): Merkley described his bill with Murphy as, potentially, a glide path to true single-payer Medicare-for-all. Under their Medicare buy-in framework, workers could leave their company’s insurance for the new public plan — but only if their employer decides to allow it. Otherwise, they’d be shut out.

(The bill does include a provision, however, allowing workers to keep the government plan once they sign up, even after they leave their current job.)

We asked Merkley why they left the decision up to the employers, not the employees. He pointed to a workers’ compensation program that had been successful in Oregon that was modeled the same way. He’s also worried about adverse selection (employers sending sick employees to the public plan while healthier workplaces stay in the private market).

Lastly, he emphasized the workers who transition to new jobs or go for a period without coverage would have a chance to sign up for Medicare and then keep that plan even after they get a new job.

“Workers can go to their employer and say, ‘I really would prefer to be in the public option,’” Merkley says. “We wanted to avoid the situation of employers pushing people out.”

The CHOICE Act (Schakowsky and Whitehouse): Small employers who are currently eligible to buy insurance through the ACA’s marketplaces would be allowed to participate in the Medicare buy-in. Workers at larger firms would be frozen out, however.

Medicare X (Bennet, Kaine and Higgins): Likewise, small employers eligible for ACA coverage could buy into Medicare under this legislation, but large employers could not. Medicare X would actually be limited to customers in Obamacare markets that had only one insurer or particularly high costs, for the program’s first few years, before expanding to the rest of the individual market nationwide.

Think tank plans

Medicare Extra for All (Center for American Progress): This plan does let employers continue to offer coverage to their workers so long as it meets certain federal standards. At the same time, it would give employers an alluring, simpler option: stop offering coverage and instead pay a payroll tax roughly equivalent to what they currently spend on health coverage.

As to how alluring that plan would be, that depends a lot on how generous this new Medicare Extra program is. A generous plan with low premiums would likely lure many away from their employer-sponsored coverage, whereas a skimpier plan with higher premiums could convince workers to stick with what they already have. These are policy details that aren’t currently specified in the CAP plan.

What’s more, Medicare Extra makes another policy decision that would erode employer-sponsored coverage: It automatically enrolls all newborns into the public program. That means a new generation of Americans likely won’t get coverage through their parents’ workplaces — and would assure the Medicare plan a constantly growing subscriber base.

Healthy America (Urban Institute): The Urban Institute explicitly designed its Healthy America plan with the goal of disrupting the large employer market as little as possible. They expect only lower-wage workers whose current insurance isn’t very good anyway to move over into the brand new insurance marketplaces that would be set up under their plan.

Those markets would combine the Medicaid population with the people currently covered by Obamacare but more or less leave people who get insurance through their jobs alone.

“That’s a real barrier to doing anything big,” John Holahan at Urban said. “Most people with employer plans are reasonably happy with them.”

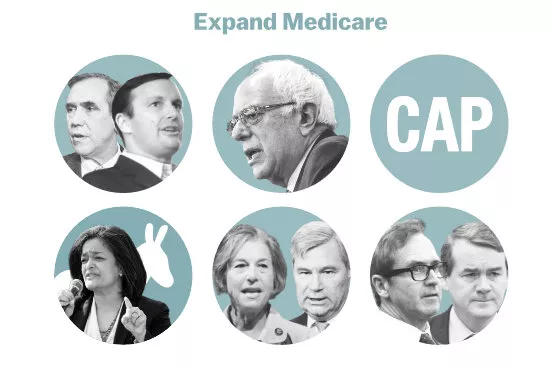

What public program will expand?

Bottom line: The vast majority of proposals expand Medicare, the plan that covers Americans over 65. But there is one option that would expand Medicaid, the plan that covers low-income Americans — and another option that creates a new government program entirely.

The American government already finances two major health coverage plans: Medicare and Medicaid. Taken together, these two programs cover one-third of all Americans: 19 percent of Americans get their coverage from Medicare, and 14 percent from Medicaid.

What’s more, both of these programs are popular. One recent poll found that 77 percent of Americans think Medicare is a “very important” program. Voters have recently given a boost to Medicaid, too: Voters in Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah all passed ballot initiatives that will expand the program in their states to thousands of low-income Americans.

Given the popularity and size of Medicare and Medicaid, nearly all the Democrats’ proposals use these programs as a base for universal coverage, changing the rules to make more people eligible. But there are differences in which programs they pick, and one plan that starts a new government program entirely.

Medicare-for-all, Medicare buy-in, Medicare Extra for All: As their names imply, all these plans use Medicare as the base program for expanding health insurance coverage. Medicare is, after all, the only major health program run exclusively by the federal government (Medicaid is run jointly with the states), which can make it an appealing choice for a national coverage expansion.

Traditionally, Democrats have focused on Medicare as a base for expanding coverage. And five of the six legislative proposals we looked at use the program that covers the elderly as the one that would absorb additional enrollees.

Medicaid buy-in (Senate and House bills): Recently, Democrats have begun to eye Medicaid as another option, suggesting that we should focus on expanding the health plan that covers the poor to Americans with higher incomes.

Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI), for example, has offered a bill that would allow every state to let residents buy into Medicaid. A companion bill is offered by Rep. Ben Ray Lujan (D-NM) in the House.

This plan wouldn’t mean moving all Americans into Medicaid — instead, it would give people the option to sign up for the public program, which would presumably offer lower premiums because it would pay doctors and hospitals lower reimbursement rates than private plans typically do.

In an interview with Vox, Schatz said he likes the idea of this Medicaid buy-in because the program has proved popular across the political spectrum. In the 2018 midterms, for example, three red states (Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah) voted to participate in Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion. “Medicaid is popular in blue, red, and purple states,” he says. “It’s not politically fraught anymore. So it’s a good place to land for progressives who want to make progress for everyone.”

Healthy America (Urban Institute): Rather than rely on any existing program, Healthy America would create a new one. Obamacare and Medicaid would effectively be combined into a brand new insurance market covering upward of 100 million people, and there would be a public insurance plan under the Healthy America brand.

What benefits get covered?

Bottom line: Democrats generally agree that health insurance should cover a wide array of benefits, although there is some variation around how different plans cover long-term care, dental, vision, and abortion.

Every country with a national health care system has to decide what type of medical services it will pay for. Hospital trips and doctor visits are almost certainly included. But there is wide variation on how health care systems cover things like vision, dental, and mental health.

Covering more services mean citizens have more robust access to health care. But that also costs money — and a more generous health care plan is going to require more tax revenue to pay for all that health care.

Even Medicare, as it currently stands, has a relatively limited benefit package. It does not cover prescription drugs, for example, nor does it pay for eyeglasses or long-term care.

Instead, many seniors often take out supplemental policies to pay for those services — or end up selling off their assets to pay for care in a nursing home.

Medicare-for-all (Senate and House)

Both single-payer options envision Medicare covering more benefits than it currently does. The Sanders bill, for example, would change Medicare to cover vision, dental, and prescription drugs, as well as long-term care services as nursing homes. It would also cover a wide breadth of women’s reproductive health services including abortion, a feature that would likely draw controversy.

The House bill covers a slightly different set of benefits but, according to one Democratic House aide, is undergoing revisions to look more similar to the Sanders package. “We want to make sure we’re able to align the coverage services [of our bill] with the Sanders plan,” said the aide, who asked to speak anonymously to discuss the ongoing negotiations.

Medicare/Medicaid buy-ins

All three notable Medicare buy-in plans would cover the 10 essential health benefits mandated by Obamacare: outpatient care, emergency services, hospitalization, maternity and newborn care, mental health and substance abuse services, and prescription drugs. None of them include vision or dental care.

The “Choose Medicare” Act (Merkley and Murphy): This bill covers essential health benefits, as well as the benefits included in Medicare’s current inpatient, outpatient, and prescription drug plans. Abortion and other reproductive services would also be covered.

The CHOICE Act (Schakowsky and Whitehouse): The ACA’s essential health benefits would be covered.

Medicare X (Bennet, Kaine and Higgins): Same. The new public plan would cover the essential health benefits dictated by the 2010 health care reform law.

“The policy would have all the ACA benefits. We’d give HHS the time and seed money to figure this out and price it,” Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA) told Vox previously. “There are studies, back from 2010, that suggest a public option would not only save money but it would make the markets more competitive.”

Think tank plans

Medicare Extra for All (Center for American Progress): The Medicare Extra plan mandates that all health insurance cover a robust set of benefits including prescription drugs, hospital visits, doctor trips, maternity services, dental, vision, and hearing services.

Healthy America (Urban Institute): The benefits package is again based on Obamacare’s essential health benefits.

How much does it cost enrollees?

Bottom line: Democrats do not agree on whether patients should pay premiums or fees when they go to the doctor. Some plans get rid of all cost sharing, while others (largely those that allow employer-sponsored coverage to continue) keep those features of the current system intact.

Medicare is currently similar to private health insurance in that it expects enrollees to pay a significant share of their medical costs.

The public program, for example, currently charges seniors a $134 monthly premium (and a higher premium for wealthier enrollees). Traditional Medicare also has deductibles and co-insurance. An estimated 80 percent of Medicare enrollees have additional coverage to help cover those costs.

The plans offered by Democrats have really different visions for whether enrollees in a newly expanded Medicare would end up paying these kinds of costs — or if premiums, deductibles, and copayments would become a thing of the past.

Medicare-for-all (Senate and House)

Both Medicare-for-all bills would eliminate cost sharing completely. This means no monthly premiums, no copayments for going to the doctor, and no deductible to meet before coverage kicks in.

The only place where enrollees might pay out of pocket is under the Sanders plan, which does give the government discretion to allow some charges for prescription drugs — but even that would be capped at $200 per year.

This is very similar to how the Canadian health care system works but is actually quite different from European countries. Most countries across the Atlantic actually do require patients to pay something for going to the doctor. In France, for example, patients are expected to pay 30 percent of the cost of their doctor visit — and in the Netherlands, copayments range from $10 to $30.

In a previous interview with Vox, Sanders said he considered copayments for his proposal but “the logic comes down on the way of what the Canadians are doing.”

The senator who rails regularly against “millionaires and billionaires” doesn’t see value in asking those people to pay when they show up at the doctor. They’ll pay more in taxes to finance a system without copayments, but when they go to the doctor, he argues, they ought to be treated the same as the poor.

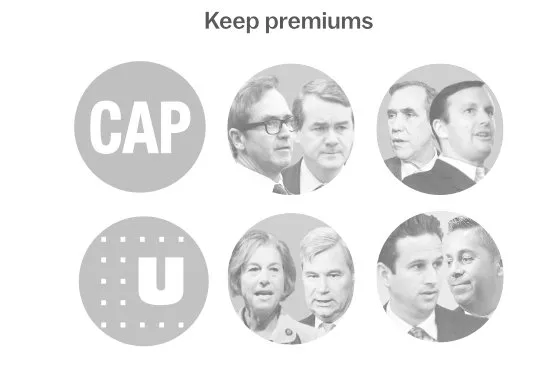

Medicare/Medicaid buy-ins

There is one important common thread through these bills: Premiums would be set to cover 100 percent of the actual medical costs that the government plan expects to cover, as well as any administrative expenses — but nothing more. There would not be any profits or robust executive compensation, as there still is in the private market. Premiums could be adjusted by a limited number of factors: a patient’s age, where they live, the size of their family, and whether they smoke tobacco.

The most notable difference in the buy-in proposal is in how much patients would be expected to pay out of pocket.

The “Choose Medicare” Act (Merkley and Murphy): This is the most generous Medicare buy-in plan. The new government plan would cover 80 percent of health care costs, matching the “gold” plans on the ACA marketplaces. The bill would also add new out-of-pocket caps for the traditional Medicare population, people 65 and older.

The CHOICE Act (Schakowsky and Whitehouse): This bill would offer several versions of the public plan, with varying out-of-pocket costs: They would cover between 60 and 80 percent of expected medical expenses.

Medicare X (Bennet, Kaine and Higgins): By default, the government plan would be offered at two tiers: one that covers 70 percent of medical costs and another that covers 80 percent. The health secretary could also decide to offer health plans covering 60 percent of costs or 90 percent, but it is not required.

Medicaid buy-in (Sen. Schatz and Rep. Lujan): The Schatz proposal would give the states leeway to decide how they want to set premiums, copayments, and deductibles. They would cap premiums at 9.5 percent of a family’s income (a provision that already exists for those covered under Affordable Care Act plans) or the per-enrollee cost of Medicaid buy-in, whichever is less.

Think tank plans

Medicare Extra for All (Center for American Progress): The plan from the center-left think tank would, unlike the congressional Medicare-for-all options, continue having some Americans pay premiums tethered to their incomes. This reduces the tax revenue necessary to finance an expanded Medicare program — but also requires a slightly more complex system that can calculate each family’s premium and collect that payment.

Low-income Americans would be enrolled in Medicare without any premiums. Higher-income Americans would be expected to pay a monthly premium (at most, 10 percent of their income) — and pay deductibles and copayments (the exact amount of these is not set in the CAP plan).

Healthy America (Urban Institute): Premiums would range from 0 percent of a household’s income, for people who make less money, up to 8.5 percent. Nobody would be asked to pay more than that.

The standard health insurance plan under Healthy America would cover 80 percent of medical costs. People with lower incomes would receive additional subsidies to reduce their out-of-pocket obligations, while consumers would also have the option to buy a plan with higher out-of-pocket costs but lower monthly premiums.

How is it paid for?

Bottom line: Most Democrats have focused their energy on figuring out what exactly an expanded Medicare program looks like. Legislators have given significantly less attention to how to pay for these expansions.

Bringing government health care to more Americans usually means finding more government revenue to pay for that expanded coverage. The Affordable Care Act, for example, expanded coverage to millions of people through a wide range of taxes that hit health insurers, medical device manufacturers, hospitals, wealthy Americans, and even tanning salons.

Right now, many of the details around financing remain murky. One reason for that is we don’t actually know how much these different plans would cost; the Congressional Budget Office hasn’t scored any of these plans yet (although there are a few independent estimates of how much the Sanders plan would cost).

Medicare-for-all

Senate: Sanders’s office has released a list of financing options that generally impose higher taxes on the wealthiest Americans, such as increased income and estate taxes, establishing a new wealth tax on the top 0.1 percent, and imposing new fees on large banks.

House: Over on the House side, aides say that while they are currently working on revisions to HR 676, that focuses mostly on updating the benefits package — and less on deciding how to pay for the package. They do not currently expect to release a financing plan in early 2019.

“Let’s get our policy straight first and then look for suggestions on financing,” says one Democratic House aide involved in the process. “It’s possible we might offer some ideas on financing, but that’s still under debate.”

Medicare/Medicaid buy-ins

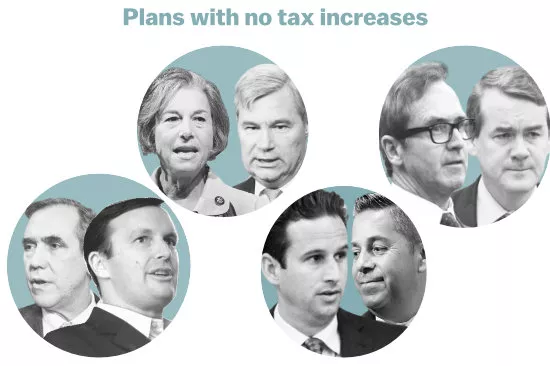

Depending on how you look at it, financing is either one big advantage of the buy-in approach or it reveals the flaw in their design. These plans still charge people premiums, which would be calculated to cover the costs of covering people who buy the new public option plan as well as any administrative costs.

So there isn’t necessarily a need for a big new revenue source; the premiums are the revenue source. None of the Medicare buy-in plans included major new taxes or anything like you would see to pay for the Medicare-for-all single-payer plans. All three of them do set aside some money for startup costs, but it’s a marginal amount in the context of the federal budget. And the Medicaid buy-in plan does bump up certain doctor payment rates, which the legislators say would come from general revenue.

The differences are so minor, they aren’t worth going through in detail. But it’s important to remember the trade-off: Medicare and Medicaid buy-ins don’t require a lot of new money because people will be asked to pay premiums — but that also means people will be asked to pay premiums, something the more ambitious versions of Medicare-for-all try to eliminate.

Think tank plans

Medicare Extra for All (Center for American Progress): Like the Sanders plan, Medicare Extra for All offers a menu of possible financing options that target the wealthy. Beyond that, Medicare Extra for All suggests one unique funding source: taxes on cigarettes and sugary beverages, as a way to raise revenue and improve public health outcomes.

Healthy America (Urban Institute): Because Healthy America combines Obamacare and most of Medicaid, the proposal is largely funded by repurposing the federal dollars that currently go to those programs. That would cover the bulk of the costs, but Urban does anticipate the need for new federal funding.

Like many of its peers, Urban isn’t yet set on a specific revenue stream, but it has floated a 1 percent increase on the Medicare payroll tax, split evenly between employers and employees. That would bring in about $820 billion over 10 years, which Urban thinks would be enough to cover most of the new costs needed to fund Healthy America.

Dylan Scott

Policy Reporter

I grew up in Ohio, lived in Las Vegas for a year and moved to Washington in 2011. I cover health care and other domestic policy. You'll probably see me tweeting about Cleveland sports or the last movie I watched.

Sarah Kliff

Senior Correspondent

Sarah Kliff is one of the country’s leading health policy journalists, who has spent seven years chronicling Washington’s battle over the Affordable Care Act. Recently, her reporting has taken her to the White House for a wide-ranging interview with President Obama on the health law — and to rural Kentucky, for a widely-read story about why Obamacare enrollees voted for Donald Trump.

Spread the word