If the trends continue, the numbers look “bleak.”

That’s the word Alden Loury, who has studied the numbers for more than a decade as a reporter, researcher and former publisher of The Chicago Reporter, uses to describe the future of the black population in Chicago in a five-part series from WVON 1690-AM.

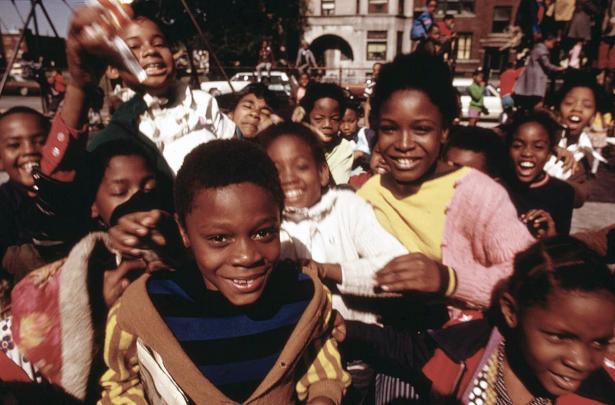

Once one of the biggest urban enclaves of African-Americans, peaking at 1.2 million in the 80s, Chicago’s black population is projected to drop to 665,000 by 2030, according to the Urban Institute.

“When I say bleak, I mean very bleak and those population numbers to me are kind of like the warning signs saying something very bad is happening here and something very bad is going to continue to happen here unless something is done,” Loury said, adding the biggest declines have occurred recently.

“Exodus: Movement of the People” uses data and expert interviews going beyond the headlines adding the political and economic climate to the raw data. Along with Loury, the docu-series features a range of experts to string together a complicated narrative including demographer Rob Paral, sociologist Eve L. Ewing and historians Timuel Black and Christopher Reed.

World War I and World War II brought a churning economy in need of workers, which attracted black people to the city. The population peaked as Mayor Harold Washington entered office and began its decline with the destruction of public housing projects.

“It’s complicated because there are lots of examples that contradict other examples. Here’s the thing, the Census Bureau shows there’s an influx of African-Americans born in Illinois, living in Georgia, which kind of makes sense. However, the African-American population of Atlanta, guess what, it’s falling,” said Paral.

While not a perfect science, one thing the numbers do show is that the population is aging.

“There are a lot fewer black children in Chicago since ten years ago,” Paral said, adding “there’s like 100,000 fewer, and we know this because all you gotta do is look at the CPS enrollment and the Charter School enrollment that basically captures kids.”

Back in 2013, Ewing was at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education when Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced the largest mass closure of public schools in the nation. On the East Coast, she was the go-to source for why this was happening even though she didn’t have all the answers.

“At the beginning of the school closures there were all these explanations for it that were given. First, it was like we’re going to save money. This is a budgetary measure and then all these analyses came out that said actually this is not going to be effective at cutting costs. Then it was like this under-enrollment idea that the schools were empty. Then it was academic like the schools are underperforming. There was always like this shape shifting rationale,” said Ewing, who chronicled those closings in her book “Ghosts in the Schoolyard.”

While the school closures left gaping holes in the South and West sides, there were outliers like Dyett High School where a tradition of community organizing helped make Chicago an enclave of black population and political power.

“What we really saw with Dyett was a group of community members saying, ‘Not today, not today. You don’t get to do that.’ Now the cost of that was they literally put their lives on the line. They were in a hunger strike for 34 days,” Ewing said.

Josh McGhee is a reporter for The Chicago Reporter. Email him at jmcghee@chicagoreporter.com and follow him on Twitter @TheVoiceofJosh.

Want more stories like this?

Get the latest from the Reporter delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe to our free email newsletter.

Spread the word