When my grandfather was a child, his stepfather would bring him along as he sold moonshine to poor working men in southwestern Virginia coal country. The men adored my grandfather, who was not yet even school age, for his talent mocking Democrats. He told me this story on a few occasions to explain, I think, the inevitability of his later affiliation with the Republican Party. He was a Republican in much the same way that I am a Democrat—voting a ticket with little enthusiasm every few years and sometimes not at all.

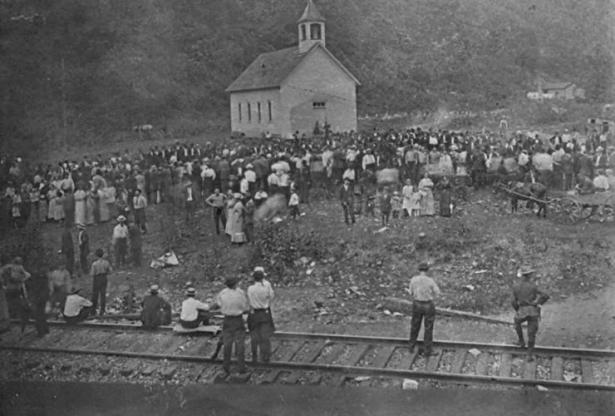

Rural spaces are often thought of as places absent of things, from people of color to modern amenities to radical politics. The truth, as usual, is more complicated.

When I consider that story now, I find myself thinking less about my grandfather and more about the men who laughed at his jokes. What were their politics? Not all were the predecessors of today’s Republicans, as we might imagine them to be. In Appalachia, so-called “mountain Republicans” comprised an old vanguard of anti- secessionists who thought of themselves as particularly enlightened—heirs, they imagined, to the legacy of Abraham Lincoln. My grandfather belonged (or at least aspired to belong) to that tradition. His audience might have consisted of Democrats, who enjoyed hearing their abuses repeated in the mouth of a child. But it is more likely that they would describe themselves as without politics, just laughing at the powerful and self-important. For a long time, it did not occur to me there were other possibilities.

My wider view of politics in Virginia’s coal country changed when I discovered that the publisher of my grandfather’s local community paper, Crawford’s Weekly, was a communist. And not just a communist in print, but a shot-while-inciting-class-war, sabotage-the-New-Deal-from-within, run-for-local-political-office-on-a-platform-of-a-producer’s-republic communist. His name was Bruce Crawford, and when my partner, also from southwestern Virginia, discovered his writings, we read them aloud to each other as though they were letters from an eccentric uncle.

Our favorite piece of his writing comes from the pages of the New Masses, a U.S. Marxist magazine that flourished between the world wars, where he announced in 1935 that he had killed his own paper because it interfered with his politics. “It was too radical for its bourgeois customers,” Crawford wrote from Norton, Virginia, “and not radical enough for me. Like capitalism, it was full of contradictions. Hence it could not go on.” The essay, “Why I Quit Liberalism,” is an exceptional piece of early #quitlit, with the same indulgent qualities. “If I get shot in the leg again, or go to jail, there won’t be that damned feeling of apology to the respectable,” he wrote. “With the more tangible roots to bourgeois life severed, I hope to know a new and meaningful freedom, whatever the hardships.”

Rural spaces are often thought of as places absent of things, from people of color to modern amenities to radical politics. The truth, as usual, is more complicated. The parents and grandparents of my childhood friends were union organizers; when my grandfather moved to East Tennessee, he went from a world of communist coal miners to the backyard of one of the most important incubators of the civil rights movement, the Highlander Research and Education Center. I now organize with people whose families have fought against economic exploitation for generations. From my vantage point in West Virginia and southwestern Virginia, what is old is new again: the revival of a labor movement, the fight against extractive capitalism, the struggle against corporate money in politics, and the continuation of women’s grassroots leadership.

The question of whether mainstream liberal opinion is shifting further left has been hotly debated in the national press after Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez won the primary for New York’s fourteenth congressional district with grassroots momentum and a socialist-friendly platform. Both conservative and liberal commentators predicted disaster, framing the twenty-eight-year-old rising political star as a gift to Donald Trump. Former Democratic congressman–turned–political pundit Steve Israel warned, “A message that resonates in downtown Brooklyn, New York, could backfire in Brooklyn, Iowa.” Nancy Pelosi waved off the win as a district-specific what-happens-in-the-Bronx-stays-in-the-Bronx phenomenon. A few months later, Ocasio-Cortez became the youngest woman elected to Congress.

In West Virginia, what is old is new again: the revival of a labor movement, the fight against extractive capitalism, and the continuation of women’s grassroots leadership.

Political veterans such as Pelosi and Israel think that the cornerstones of the emerging left platform—housing as a human right, criminal justice reform, Medicare for all, tuition-free public colleges and trade schools, a federal jobs guarantee, abolition of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and for-profit prisons, campaign finance reform, and a Green New Deal—might perform well in urban centers but not so much elsewhere. Appalachia has become symbolic of the forces that gave us Trump. After all, his pandering to white racial anxiety did find purchase here. His fantasies to make America great again center on our dying coal industry. And the region’s conservative voters, who have been profiled endlessly, have been a reliable stand-in for all Trump voters, absorbing the outrage of progressive readers. But what Pelosi and Israel see as common sense and pragmatism can also be interpreted as tired oversimplifications and a failure of imagination.

We remain attached, after all, to narratives that have worked very hard to simplify and neatly divide the state of the union: blue cities, red rural areas, a few swing suburbs. “In a period of political tumult, we grasp for quick certainties,” sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild writes in Strangers in Their Own Land (2016). Indeed, the biggest gift that the left has given the right since 2016 is not a few avowed socialists but the myth that Trump voters are inscrutable and monolithic. “I love Cleveland, but I’ve always considered it separate from Ohio,” resident Julie Goulis told the Guardian just before the 2017 inauguration. “Some of the soul-searching I’ve been doing after the election has been about how I can understand people outside of my bubble.”

It would be far better for progressives to save their bubble-popping for moments such as this, when an opportunity emerges to better understand those closer on the political spectrum in those same spaces. The limbo we are trapped in compels white progressives to see themselves in a Trump voter rather than in a rural socialist or communist—or even a rural person of color, who faces many of the same struggles as the Trump voter, perhaps even more pronounced, and chooses a different way forward.

Let us get free of that, once and for all. Appalachia should not be seen as a liability to the left, a place that time and progress forgot. The past itself is not a negative asset. The hierarchies and systems of power here feel old because they are, but this legacy also means there are many who are well practiced in the art of survival and resistance. Our present can be reckoned with, and a different future emerge, but the way forward for the left, in my world, is through the past.

***

When Ocasio-Cortez asks if voters are prepared to choose people over money, I hear echoes of a much older question that still resonates in Appalachia: Which side are you on? In 1931, when Black Mountain Coal Company cut miners’ wages in Harlan, Kentucky, a long strike ensued. Harlan’s infamously corrupt sheriff, J. H. Blair, terrorized union families; law enforcement, including the National Guard, intervened on behalf of the interests of coal operators to force miners—through threats, coercion, and violence—to return to work. When the sheriff and deputized coal company operatives ransacked activist Florence Reece’s home in search of her husband, who helped organize the strike, Reece penned what would become one of history’s most recognizable labor anthems, “Which Side Are You On?” The song galvanized workers and inspired bystanders to surrender the illusion that one could be impartial in the face of so much oppression. “Us poor folks haven’t got a chance unless we organize,” she sang. “They say in Harlan County there are no neutrals there.”

Reece set her humanity against the plundering coal bosses who controlled every aspect of her family’s life. Striking at the legitimacy of the ruling class, her question became immortal, useful not only to workers but, later, to civil rights activists. Would a candidate with Ocasio-Cortez’s platform fail in Appalachia? Perhaps. But people would find themselves animated to hear old questions in a new context, attached to new possibilities. In fact, some already have.

Appalachia should not be seen as a liability to the left, a place that time and progress forgot. The past itself is not a negative asset.

In late 2016, for example, a young man named Nic Smith, another product of southwestern Virginia, made headlines for his participation in a #Fightfor15 demonstration. Outside a Richmond McDonald’s, Smith, a Waffle House employee, connected the plight of fast-food workers with the past struggles of coal miners in his family. He also pushed back against the Trumpian reactionary politics that elevates white working-class racial anxiety over class solidarity. “Ain’t no damn immigrant stole a coal job,” Smith said. “I’ll tell you that right now. And really, even if they did, would you really be blaming the immigrants or the people that hired them? The only reason they would hire an immigrant over an American citizen is if it benefits their wallets.”

Instead of rigging a dying industry, Smith explains in a Washington Post op-ed, it would be far better to unionize low-wage workers and raise the minimum wage. He joined #Fightfor15, he wrote, because his family “has always understood that we can’t wait for a savior at the ballot box to shepherd in the change we so desperately need.”

A self-described “damn white trash hillbilly from the holler,” Smith is an exotic figure to the many media outlets that covered him. VICE complimented him for not fitting “the image of the typical millennial activist”—a former factory worker, you see, who “isn’t the kind of Democratic Socialist who spouts off at Brooklyn parties about the ‘means of production.’” Smith’s approach is fairly typical, however, if you are looking from Appalachia rather than New York. Here, activists such as Smith often connect to the struggles of their parents and grandparents as they engage in activism.

For decades, this distinct motivation has been at the heart of much of the success that the left has seen elsewhere. Helen Lewis, a beloved Appalachian educator who became an activist in the 1940s, taught poor people economic history to prime them for organizing. She began by asking them what their grandparents did for a living, then what their parents did. This strategy inspired generational thinking, and, according to historians Jessica Wilkerson and David P. Cline, Lewis’s bottom-up Appalachian Studies “influenced a cadre of activists, including grassroots leaders and white civil rights activists who migrated to the mountains to build alliances with rural whites.” Learning about the region’s history, whether through one’s family or formal study, is often a crucial step in helping people understand that their struggles are a new battle in an old war.

Brandon Wolford, for example, a teacher from Mingo County, West Virginia, grew up watching news footage of 1980s miners’ strikes that his father participated in. The price of coal had declined, and companies such as the Pittston Coal Company tried to recoup their losses by slashing workers’ wages and benefits. In the case of Pittston, the United Mine Workers of America eventually prevailed, winning back many protections and securing others, although coal’s economic slump made it difficult for organized labor to rebound fully. The memories of those and other labor victories, however, stayed with families. “Knowing the role my father and both grandfathers had played in these events sparked a special interest,” Wolford wrote in 55 Strong: Inside the West Virginia Teachers’ Strike (2018). “I wanted to be involved in a movement like that someday.”

In February of 2018, Wolford joined more than 20,000 West Virginia teachers and public school employees who went on strike to force state leaders to reckon with inflated insurance premiums, low pay, and a widespread teacher shortage. The strike closed schools in all 55 counties for 9 days and endured even after union support stopped. It ended with a 5 percent pay raise across the board and a pledge from state leaders to reexamine the state’s public employee insurance agency.

To create solidarity in the present, to make change for the future, West Virginians needed to remember their radical past.

The West Virginia teachers’ strike emerged as one of the clearest visions of the new labor movement. It inspired education strikes in other states, including Kentucky and North Carolina. But understanding the strike requires knowing a century of southern West Virginia history, notably its infamous labor uprisings, from the Mine Wars of the 1920s to big coal’s union-busting campaigns of the 1980s. When momentum to strike built in early 2018, teachers in West Virginia’s coal country were among the first to mobilize and put action to a vote. In a Facebook group, they used coal country’s labor history to portray the strike as not only urgent and just, but also natural—something that people like them had been doing for generations. In a speech at a countywide meeting, Katie Endicott, an English teacher from Mingo County, emphasized the familiarity: “If we can do this, if we can stand, then we know that our brothers and sisters in Wyoming are not going to let us stand alone. We know that our brothers and sisters in Logan County will not let us stand alone. The south will stand. And if the south stands, the rest of the state will follow our lead.”

To create solidarity in the present, to make change for the future, West Virginians needed to remember their radical past. To the extent that collective action requires a public narrative—a story that helps consolidate its moving parts and moral purpose—West Virginia’s south played its part exceptionally.

***

This past sits uneasily within Joe Manchin’s vision of West Virginia. In the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, Manchin, the state’s former governor and second-term Democratic senator, became a favorite of pundits. They predicted that Democrats’ only lifeline would be replicating his limp style of centrist politics. An Atlantic essay titled “What Joe Manchin Can Teach Democrats” touted Manchin’s utility as “a sounding board for, and bridge between, his party’s leadership and conservative, rural, white voters.” Manchin’s vote to confirm Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court amid allegations of sexual assault did little to dim pundits’ rose-colored view of the great moderate. Manchin was better than no Democrat at all, they reasoned—the best West Virginia can do.

Yet as writer Aaron Bady, a West Virginia native, counters, “It’s because I am burdened with a handful of facts about West Virginia—and a memory that goes back more than two years—that this kind of analysis stands out as the garbage that it is.” One of these facts is the 1996 gubernatorial race, in which Manchin was outflanked on the left in the Democratic primary by Charlotte Pritt. Pritt’s anti-corporate platform alienated coal industry power players; Manchin, a coal millionaire, convinced a coalition of Democrats to finance and support Pritt’s Republican challenger, Cecil Underwood. For many observers, Manchin’s vengeance went beyond politics: Pritt was a teacher and the daughter of a coal miner, you see; she was a worker and she beat an owner. The ’96 election and Manchin’s later political ascent prove less about the left’s potential in West Virginia than they reflect a common truth: bosses cheat to win.

West Virginia’s workers, whether coal miners or teachers, have never benefitted from the state’s natural wealth due to greedy corporations and the politicians they buy.

This fact of life has been proven once again by Richard Ojeda, a West Virginia state senator who recently parlayed an unsuccessful bid for Congress into the beginnings of a presidential campaign, one of the first in the Democrat’s 2020 field. Ojeda became an outspoken defender of teachers during their strike, and he garnered a lot of attention by reminding West Virginians of their history. “Teachers are joining a fight for the soul and spirit of West Virginia that started hundreds of years ago,” he wrote in a long Twitter thread. “Hundreds of years ago, investors came to West Virginia and purchased most of the land for all but nothing. Even today, you will be hard pressed to find many people in WV who own their mineral rights.”

His logic is simple: West Virginia’s workers, whether coal miners or teachers, have never benefitted from the state’s natural wealth due to greedy corporations and the politicians they buy. Ojeda’s plainspoken, often angry distillations of the state’s woes, and his tender attention to the plight of teachers, grabbed national attention. He was featured as an example of someone who could turn the tide for Democrats in “Middle American places where their party used to prevail, but has been decimated in the Trump era,” as journalist Trip Gabriel suggests.

Ojeda’s willingness to stoke rather than soothe the growing militancy of West Virginia’s rank and file undermines the claim that West Virginia is doomed to centrist Democrats. His success should not be underestimated. But, like Manchin and current governor Jim Justice (a lifelong Republican who got elected as a Democrat only to defect back to the GOP), Ojeda also has a history of straying to the right. Ojeda voted for Trump (a decision he now says he regrets) and has said he might switch teams. Moreover, Ojeda’s evasiveness about the appeal of Trump’s racism among West Virginia voters makes it difficult to embrace him as a unifying leader of the rural left. Indeed, I am reminded of former Republican senator James E. Watson’s response to Wendell Willkie when Willkie switched parties, from Democrat to Republican, to run for president in 1940. Asked by Willkie if he believed in the power of conversion, a skeptical Watson replied, “It’s all right if the town whore joins the church, but they don’t let her lead the choir the first night.”

Ojeda’s presidential bid also sends a strong signal that he approves of the media ecosystem that has branded him a novelty. That novelty is dangerous, not least because pundits and political reporters are eager to propagate the idea that to win in places such as West Virginia—and now, it seems, the nation at large—the left needs its own version of Trump: a brash populist, prone to macho posturing, with a no-bullshit persona and little time for the rules or party politics.

But the more Ojeda’s star rises, the further it departs from its grassroots origins, including a labor movement that is 75 percent women. In a story announcing Ojeda’s presidential bid, for example, the Intercept initially ran a headline that referred to him as the leader of the teachers’ strike—not just a vocal supporter. This mistake, although minor and originating from editors and not Ojeda’s team, is reminiscent of the historical erasure of women’s political work in Appalachia, particularly of women such as Pritt who are further to the left of West Virginia’s Democratic establishment. More recently, there was Paula Jean Swearengin, Manchin’s primary challenger and environmental activist, and Talley Sergent, who performed just as well as Ojeda in the recent midterms without generating a fraction of his national interest.

***

It matters that workers are rising up, and it matters that women are leading. It matters that the fight against extractive capitalism is fiercer than ever.

The 2016 election still looms over us. But if all you know—or care to know—about Appalachia are election results, then you miss the potential for change. It might feel natural to assume, for example, that the region is doomed to elect conservative leadership. It might seem smart to point at the “D” beside Joe Manchin’s name and think, “It’s better than nothing.” There might be some fleeting concession to political diversity, but in a way that makes it the exception rather than the rule—a spot of blue in Trump Country.

If you believe this, then you might find these examples thin: worthy of individual commendation, but not indicative of the potential for radical change. But where you might look for change, I look for continuity, and it is there that I find the future of the left.

It matters that workers are rising up, and it matters that women are leading. It matters that the fight against extractive capitalism is fiercer than ever. And for all of these actions, it matters that the reasoning is not simply, “this is what is right,” but also, “this is what we do.” That reclamation of identity is powerful. Here, the greatest possible rebuke to the forces that gave us Trump will not be people outside of the region writing sneering columns, and it likely will not start with electoral politics. It will come from ordinary people who turn to their neighbors, relatives, and friends and ask, through their actions, “Which side are you on?”

“Listen to today’s socialists,” political scientist Corey Robin writes,

and you’ll hear less the language of poverty than of power. Mr. Sanders invokes the 1 percent. Ms. Ocasio-Cortez speaks to and for the ‘working class’—not ‘working people’ or ‘working families,’ homey phrases meant to soften and soothe. The 1 percent and the working class are not economic descriptors. They’re political accusations. They split society in two, declaring one side the illegitimate ruler of the other; one side the taker of the other’s freedom, power and promise.

This is a language the left knows well in Appalachia and many other rural communities. “The socialist argument against capitalism,” Robin says, “isn’t that it makes us poor. It’s that it makes us unfree.” Indeed, the state motto of West Virginia is montani semper liberi: mountaineers are always free. It was adopted in 1863 to mark West Virginia’s secession from Virginia, a victory that meant these new citizens would not fight a rich man’s war.

There are moments when that freedom feels, to me, unearned. How can one look at our economic conditions and who we have helped elect and claim freedom? But then I imagine the power of people who face their suffering head on and still say, “I am free.” There is no need to visit the future to see the truth in that. There is freedom in fighting old battles because it means that the other side has not won.

Elizabeth Catte is a writer and public historian based in the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia. She is the author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia.

Become a Member

Engaged discussion of social and political issues is a fundamental public good. That's why Boston Review keeps its website and archive open to all readers—without paywalls or any commercial ads.

Your membership directly supports our mission to provide a free space for an open exchange of ideas. Memberships at each tier include a subscription to our quarterly issues, plus added benefits. Find the level that's right for you.

Spread the word