film Native Son Is an Imperfect But Mesmerizing Adaptation of Richard Wright’s Classic Novel

Richard Wright published his groundbreaking novel Native Son in 1940, the tale of a 20-year-old African-American man named Bigger Thomas living on the south side of Chicago. It’s a story in three parts (named “Fear,” “Flight,” and “Fate”), one that vividly illustrated the deck that was stacked against young black men like Bigger, even when they tried to outmaneuver it.

What’s most startling and devastating, then, is that Pulitzer-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks didn’t have to change much about Wright’s nearly 80-year-old story to set it in a contemporary Chicago. Conceptual artist Rashid Johnson directed Parks’s adapted screenplay, and the resulting film was selected to open the 2019 Sundance Film Festival.

And though it has some problems as a film — some of which are part and parcel of translating a book to the screen — Native Son still packs a punch, one that connects directly with the gut.

Native Son is about a young man’s collision with a world where he’s always an outsider

Some critics — most notably James Baldwin — denounced Wright’s novel for painting Bigger as more of a stereotype than an actual character, and some of those broad strokes transfer over to the film.

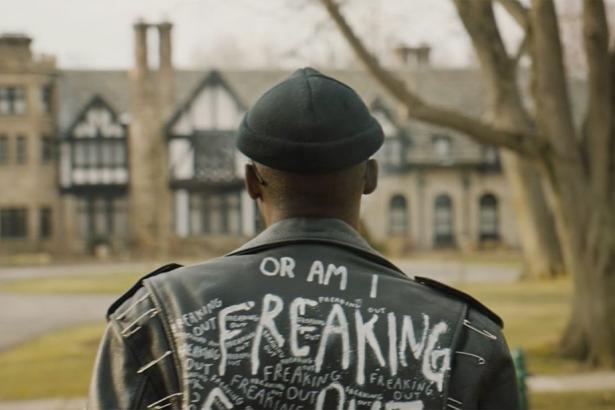

But fortunately, Bigger is portrayed by Ashton Sanders, in his first major film role since he played the teenage Chiron in the 2017 Best Picture-winning Moonlight. Lanky and charismatic, sporting grass-green hair and a leather jacket covered in slogans and pins, Sanders’s take on Bigger (or “Big,” as his friends call him) fills out the character. Big starts out as a maverick, a whirlwind of potential, and ends up as another statistic — and Sanders’s performance ensures we wholly understand what a tragedy that is. In this version of Wright’s story, Big lives with his widowed mother (Sanaa Lathan) and his siblings on the south side, and works as a bike messenger during the day. The film’s first section (“Fear”) strikes a similar tone to the novel’s first section: Big meanders through his day, encountering friends, acquaintances, enemies, and his girlfriend (KiKi Layne, fresh off her starring role in If Beale Street Could Talk) and narrating, in voiceover, a series of musings about himself and his future that form a kind of counter-melody to what he says out loud.

Big doesn’t want to get drafted into the business of selling drugs that many of his friends have gotten into, but being a bike messenger is a bit of a dead end, and he wants more. His mother’s affable boyfriend (David Alan Grier) tells him about an opportunity to drive for a wealthy white man, Henry Dalton (Bill Camp), and he gets the job.

And it’s a good one. It comes with a room in the family’s palatial home, where Henry, his blind wife (Elizabeth Marvel), and their college-aged daughter Mary (Margaret Qualley) live. The Daltons are a liberal-minded family, the kind that’s hard to see on screen these days without thinking of the “I would have voted for Obama a third time” white liberal family of Get Out.

Big was hired to drive for the whole family, but his time is quickly monopolized by Mary, who asks him to take her to political populist movement meetings, then to drive her and her boyfriend Jan (Nick Robinson) to parties or a late-night hangout.

It all feels a little familiar and cringe-y — it’s very uncomfortable to watch Big don an acquiescent smile when his new employers try to prove how chill they are — but then things go horribly awry one night, and Big is left dealing with the consequences for his future.

It’s rough around the edges, but Native Son’s story still resonates

The material here is so good, and Sanders is so magnetic as Big, that Native Son’s uneven and at times jarring direction is more or less forgivable. It’s always a relief and a joy to see a distinctive cinematic vision working itself out on screen, and even if the results feel a little herky-jerky by the end, it’s refreshing to see a filmmaker go for it.

That said, Native Son will probably baffle some audiences and frustrate others. The task of translating Big’s inner life to the big screen is largely left up to the voiceover, which at times feels like it’s in danger of spinning off into platitudes or stereotypes. The story progresses in fits and starts; every time you feel like you’ve locked into it, it seems to slam on the brakes and veer off around the corner, or to change the radio station before the current song is over.

Then again, that’s fitting for this story. Part of Big’s dilemma is he doesn’t feel like he fits in anywhere. He sticks out from the peers he grew up with, something he makes clear to us in his voiceover. He can only slip into his employers’ world because he’s willing to overlook a hundred little acts and statements per day that reduce him to a type, to whoever they think he is rather than who he actually is. And America sure isn’t going to make room for him if he refuses to fit into the neat little boxes prescribed for him.

At one point Big talks about his double consciousness, a theme that’s been part of black American storytelling for a long while, at least back to W.E.B. DuBois and his 1903 autoethnography The Souls of Black Folk and extending through much pop culture created by black filmmakers and storytellers. Just last year, at least three Sundance premieres — Sorry to Bother You, Tyrel, and Blindspotting — were all at least partly driven by the conflicts inherent in double consciousness, code-switching, and identity in contemporary black America.

What’s unique about Native Son, despite its flaws, is that it takes such an old story and, with very little tweaking, sets it now. That very act points to how, when it comes to race in America, little we’ve evolved over the last 80 years, despite our self-congratulations. Big’s tragedy, and America’s, is that things change a lot, and yet it’s striking how much they stay the same.

Native Son premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and is slated to debut on HBO in April 2019.

Alissa Wilkinson is Vox's film critic. She's been writing about film and culture since 2006, and her work has appeared at Rolling Stone, The Washington Post, Vulture, RogerEbert.com, The Atlantic, Books & Culture, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Paste, Pacific Standard, and others. Alissa is a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and a 2017-18 Art of Nonfiction writing fellow with the Sundance Institute.

Spread the word