Milton Cayette Jr. has just returned from a birthday party at the senior center in Welcome, one of the unincorporated hamlets nestled beside the earthen levee running along the east bank of the Mississippi River in the 5th District of Louisiana’s St. James Parish. Sitting in the kitchen of his home, Cayette begins listing the petrochemical facilities in the area, starting about five miles upriver near the Sunshine Bridge, where a chemical plant run by the company Mosaic produces diammonium phosphate and ammonia. Next door another plant produces styrene, a chemical used to make rubbers and plastics. Beyond these plants, the steaming stacks of a large nitrogen complex rise up behind a tree line.

Between these plants and Welcome lie large tracts of agricultural land slated to host a $9.4 billion plastics plant proposed by the Taiwanese company Formosa. The plant would be the largest of its kind in the sprawling industrial corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans — the zone commonly called “Cancer Alley” by local activists and environmentalists. Dubbed the “Sunshine Project” due to its proximity to the bridge, Formosa’s plant would use “ethane crackers” to turn natural gas products into feedstock for making artificial turf, throwaway bottles, grocery bags and other plastics.

Formosa wants to build just over a mile from Welcome, where a local pastor is building a new church for his congregation at the edge of town, not far from the local elementary school. The plant would emit roughly 28 million tons of air pollutants each year, including large amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, according to a permit application. Tons of health-endangering pollutants, including volatile organic compounds like benzene and toluene, which are known to causecancer and acute health problems, would be released as well.

A large-scale methanol plant for processing natural gas made dirt-cheap by the fracking boom is also on the way, thanks to backing from Saudi Arabian petrochemical interests. Across the river, two Chinese companies are working on their own chemical and menthanol plants. Downriver from Cayette’s home, oil and gas pipelines feed expanding “tank farms” between the east bank neighborhoods of St. James.

“It’s a shame, all the plants,” Cayette says. “It’s not getting any better. They are putting all their pollutants out into the air, and in the water, and in the ground. I do worry about my health, with the air, I surely do.”

Milton Cayette in the kitchen of his home near Welcome, Louisiana. Cayette worries about impacts that air pollution from the expanding petrochemical industry could have on his community. Laura Borealis

I ask Cayette about the other Mosaic facility across the river, a fertilizer plant where crews have been working around the clock to reinforce a 200-foot wall of gypsum that contains a massive pond of acidic wastewater. Mosaic recently reported that the impoundment was unstable and slumping, raising fears that a potential breach would allow hazardous waste to come flooding out. Cayette cracks a wry smile and points out that the Mississippi River would carry pollution away before it reaches his property, but people downriver might not be so lucky.

“It all started in 1965 when we had Hurricane Betsy,” Cayette says. “And that’s when all these plants start coming up.”

Cayette was 14 years old when Hurricane Betsy ravaged southern Louisiana, causing record damage in New Orleans and beyond. Before the hurricane, Cayette remembers gathering blackberries, pecans, honeysuckle and maypop fruit along the river. The area had been agricultural since the plantation days, when free people of color who survived slavery established settlements along the river. About 86 percent of the roughly 2,800 people currently living across the 5thDistrict’s unincorporated hamlets are Black.

Cayette’s father planted corn, but everything changed after the storm. Farmers began spraying their sugar cane fields with harsh pesticides as heavy industry crept into the area, replacing farms across St. James and neighboring parishes. By 1968, Cayette says, blackberries and pecans were difficult to find. Nowadays, odors associated with petrochemicals are a fact of life. From 2017 to 2018, 37 chemical accidents were recorded in St. James Parish, including the releases of noxious fumes and reports from residents of strong chemical odors in the air. Residents in the 5thDistrict report skin rashes, difficulty breathing and cases of cancer, according to a letter to local officials written by Cayette’s sister, Sharon Lavigne.

“We already half dead for the graveyard, but they are trying to put us in the graveyard,” Lavigne said during an interview at her nearby home.

This story is a familiar one in Cancer Alley. For decades, historic but often unincorporated Black communities have been wiped off the map out by encroaching industry, typically after air and groundwater pollution made neighborhoods unlivable and residents demanded that companies buy out their homes. Cayette and Lavigne fear they could be next if Formosa moves in next to the chemical plants already humming down the road.

Two chemical plants are already in operation between the hamlet of Welcome, Louisiana and the nearby Sunshine Bridge. A large petrochemical and plastics plant proposed by the Taiwanese company Formosa and a methanol production facility are also in the works. Laura Borealis

The industry is known for getting its way in Louisiana, and the federal government has a dismal record when it comes to holding polluters accountable for environmental racism. However, local activists are fighting back with help from allies from across the river and across the country. With the anxiety over climate disruption and plastic pollution in the world’s oceans reaching a fever pitch, the fight against Formosa could thrust the rural communities in St. James into the global debate over the future of fossil fuels.

“Read My Lips: We Don’t Want You Here”

The people who showed up to speak at a late January meeting of the St. James Parish Council fell into two camps. On one side were representatives from Formosa and a methanol company, along with a few local supporters with jobs in the industry. On the other side were opponents of new industrial development, including members of RISE St. James, a faith-based group Lavigne founded to challenge Formosa just months earlier. The majority-white council was poised to clear a crucial hurdle for the facility and approve a renegotiated land-use agreement with Formosa, but they took comments from the public first.

“Read my lips: We don’t want you here,” said RISE member Rita Cooper. “We are already dying.”

RISE St. James activist Rita Cooper addresses the St. James Parish Council in January. Despite vocal opposition from residents, the council approved a crucial land-use agreement for the proposed Formosa plant. Laura Borealis

Despite protests, heated public hearings and the company’s record of chemical accidents and pollution, Formosa’s proposal is sailing through the approval process at the state and local level. Political support for the plant runs straight up to Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat with red state pedigrees. State officials offered the company lucrative incentives for locating in St. James, including $12 million in infrastructure grants and access to workforce and tax exemption programs. Formosa has promised to create 1,200 permanent jobs, and the state expects $362 million in new tax payments during the plant’s construction phase alone, according to a state release.

While researching the proposal, environmentalists discovered that a 2014 “comprehensive plan” produced by the St. James Parish government had designated the Welcome and St. James portion of 5th District as an “industrial” and “residential/future industrial” on map detailing future land-use. About 1,500 people live in the area, and over 90 percent are Black, according to census data. The fact that a longtime residential community tracing its roots back to freed slaves would be labeled “industrial” set off alarm bells among residents and environmentalists.

“I could have sworn we were here first,” Stephanie Cooper, a local schoolteacher, told the council.

Environmental groups recently filed a sweeping request with local officials for public records on the decision-making process behind the land-use designation. The Center for Biological Diversity, a non-profit known for using litigation to challenge polluters nationwide, filed a lawsuit earlier this month against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers over a separate request for federal records related to Formosa’s application to dredge in the Mississippi River. The information requests are the first shot in what could be a lengthy battle over the Sunshine Project.

The authors of the comprehensive plan wrote that it is “not a forecast of future events, but rather a well thought out strategic plan” that includes input from a steering committee of citizens and public meetings. A spokesperson for FG LA LLC, the Formosa subsidiary seeking to build in St. James, said in an email that “hundreds” of St. James Parish citizens have expressed support for the Sunshine Project’s proposed ethane crackers. Activists and 5th District residents want to know exactly who they talking about.

“I would like to know how they went about making where I live industrial,” Lavigne said in a statement last month. “Parish officials say that people of the 5th District — my district — were in favor of the land-use plan, but everybody I talk to who lives here is against more industry coming here. That’s why we want these records, to find out what really went on back in 2014.”

After hearing emotional testimony from environmentalists, representatives from Formosa addressed the parish council, promising to install pollution monitors and provide 5th District residents with health screenings after the plant is built. They also agreed to provide a free job-training program for area residents, although jobs at the plant would not be guaranteed. The council then voted to approve the land-use agreement, a major victory for Formosa.

“I hope that they will keep their word,” said Clyde Cooper, the 5th District councilman.

An Environmental Violation of Civil Rights?

Sitting in the living room of her home in the 5th District, Lavigne says it’s no secret that the petrochemical industry is being allowed to choke out her community because it’s low-income and a majority of residents are Black.

“They don’t think we are human beings, I guess,” Lavigne says.

RISE St. James founder Sharon Lavigne in the living room of her home in the 5th District of St. James Parish. Lavigne wants to know why local officials designated her community as “industrial” and “residential/future industrial” in a 2014 future land-use plan.

Lavigne was born when Jim Crow laws still ruled the South, and her father fought to desegregate the high school where she now works as a teacher. Holding a picture of her father standing in a row of women who challenged school segregation with him decades ago, Lavigne recalls that his truck was once set ablaze in retaliation. At least they didn’t burn down his house, she says.

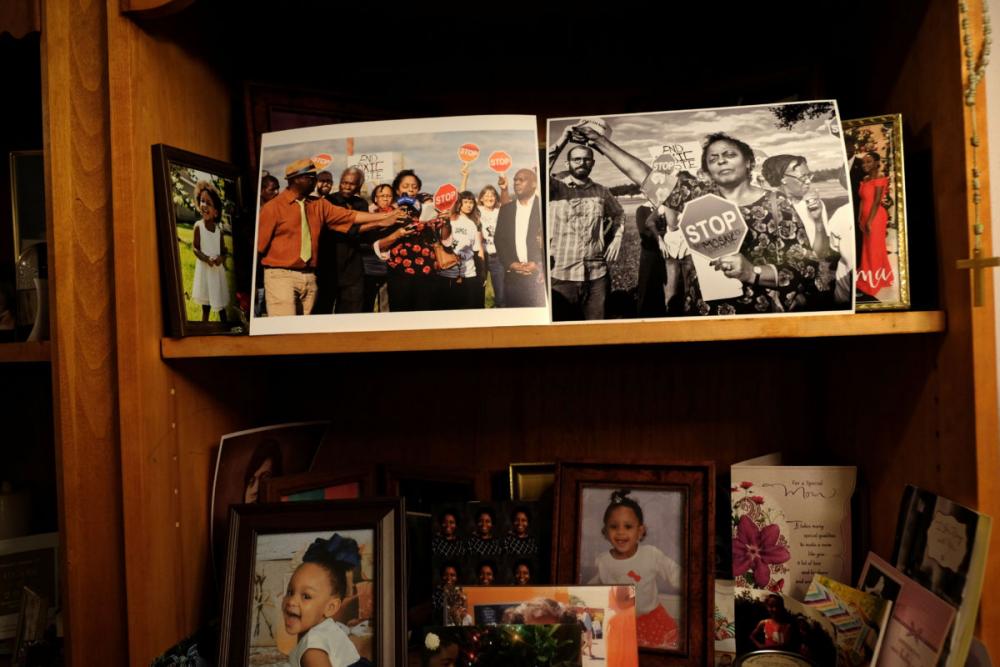

A shelf in Sharon Lavigne’s living room displays photos of her family and her activism. Lavigne’s father fought to desegregate the high school where she works as a teacher. Laura Borealis

For Lavigne, the Formosa proposal is proof that democracy still has not come to St. James Parish. In her letter to local leaders, Lavigne warned that the proposal is a “civil rights violation as well as a public relations nightmare.” In December, Lavigne laid out her case in a letter to a local newspaper:

Formosa Plastics was mandated to consider five sites when it applied for its wetland permits. Instead, Formosa submitted three proposed sites, all in predominantly black neighborhoods. Formosa couldn’t even come up with the required two other alternative sites, let alone one in a nonblack neighborhood. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and Article IX of the Louisiana constitution are supposed to protect black communities from this type of environmental racism. They haven’t in Cancer Alley.

In a statement, a spokesman said Formosa went through “an extensive site selection process” and chose the site near Welcome because the area is designated for industrial use and is as far away as possible from “all people of all races, given the constraints of the project.” It’s this industrial land-use designation, along with permit applications, that environmental groups are currently investigating. Councilman Cooper and the parish council chairman did not respond to a request for comment.

A local pastor in Welcome is building a new church at the edge of town, just over a mile from the site of the proposed Formosa plastics facility. The original church is further down the road, near the local elementary school. Laura Borealis

Plenty of data from across the country shows that sources of industrial pollution are more likely to be located near low-income communities and neighborhoods of color, and Black and Latinx people often bear the bruntof toxic accidents and emissions. More than 200 complaints filed with the Environmental Protection Agency’s civil rights division have been rejected or dismissed after languishing in an extensive backlog for years. In a landmark ruling last year, a federal court found that the EPA had violated the Civil Rights Act by dragging its feet on environmental justice enforcement.

The ruling has given new hope to environmental attorneys who are eager to use the Civil Rights Act as a tool to fight discrimination. Environmentalists often challenge polluters by targeting permits issued under the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, but federal agencies like the EPA and Army Corps of Engineers must also comply with the Civil Rights Act, which forbids federal spending on programs or activities that discriminate based on race. An executive order issued by President Clinton in 1994 goes even further, requiring environmental regulators to address disproportionate impacts of pollution on minority populations, although this directive has proven difficult to enforce. Major federal permits for the Formosa plant are still in the works, and environmental groups are watching closely.

Adrienne Bloch, an attorney for the environmental group Earthjustice, told Truthout that observers believe emissions from Formosa plant would increase local cancer risks in an area where resident say air pollution is already causing health problems.

“For instance, the ethylene oxide emissions will cause ambient levels of ethylene oxide that are 246 times that which EPA has found can cause cancer,” Bloch said in an email. “Formosa and the state must ensure that this kind of harm to public health will not occur.”

A Local Struggle and a Global Debate

For national groups like Earthjustice, the fight in Cancer Alley is not just about environmental racism and cancer rates. Thanks to the fracking boom, the U.S. is poised to become the world leader in oil and gas production. Prices have plummeted, particularly for natural gas products, which would feed Formosa’s proposed ethane crackers and nearby methanol facilities in St. James. Meanwhile, growing global panic over climate disruption threatens to reduce demand for oil and gas in the energy sector as forward-thinking countries attempt to reduce carbon emissions over the coming decades.

Now, the petrochemical industry is building new “cracker” facilitiesacross the world to make plastics, soak up cheap gas and maintain demand for fossil fuels. By 2023, at least $164 billion will be spent on 264 new plastics facilities or expansion projects in the U.S. alone, and a good chunk is going to Cancer Alley. Throwaway plastics are a persistent pollutant, particularly in the world’s oceans, where trash islands make alarming headlines and tiny bits of plastics are penetrating deeper into organisms and ecosystems than previously thought. If current consumption trends continue, analysts estimate that the plastic manufacturers would consume 20 percent of the oil produced globally by 2050, and the amount of plastic in the world’s ocean would outweigh the entire mass of fish still living in them.

With a disappearing coastline and historic storms and floods, Louisiana is already experiencing frontline impacts of climate disruption, but Edwards and other leaders are banking the state’s economic future on natural gas and plastics. Natural gas is considered to burn cleaner than other fossil fuels, but the Formosa plant alone would produce more than 27 million tons of greenhouse gases a year. This puts Louisiana and Cancer Alley at the center of some of the biggest environmental debates today, and the industry is racing to build infrastructure and lock in decades of profit before public opposition reaches a breaking point.

A yard sign opposing Formosa’s proposed “ethane cracker” plant near Welcome, Louisiana. The plant would generate feedstock for common plastic products, including grocery bags and throwaway bottles. Laura Borealis

Activists across the U.S. are taking notice. Last month, RISE St. James held a gospel-style “moral revival” and rally with the Poor People’s Campaign and Rev. William Barber, the civil rights activist known for the Moral Mondays movement in North Carolina. Activists from across Cancer Alley and southern Louisiana gathered to sing, dance, pray and testify. Joining them were water protectors who spent the past year fighting the Bayou Bridge Pipeline despite a new state law making protests around industrial infrastructure a felony offense. Considered the southern leg of the Dakota Access Pipeline that met fierce resistance at Standing Rock, Bayou Bridge bisects southern Louisiana and will feed the “tank farms” downriver from Welcome in St. James.

As Rev. Barber began his keynote speech, he asked audience members to raise their hands if they knew someone who had died from cancer in Cancer Alley. Hands flew up across the room.

Lavigne says she has seen enough illness in her community to know that existing sources of pollution are causing problems, and the addition of one more plant will make her neighborhood unlivable. Still, Lavigne says the moral revival was a bright spot in the RISE campaign to stop Formosa, and she is not losing faith. She recently gathered 537 signatures on a petition to the parish zoning commission; buses of activists are arriving from New Orleans. In November, RISE St. James held a march against Formosa, and Lavigne is already thinking about the next one.

“I asked God what I could do to stop this plant from coming, and He said ‘fight,’ and I haven’t stopped since,” Lavigne says. “And that plant isn’t coming.”

Copyright, Truthout. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission.

Mike Ludwig is a staff reporter at Truthout and a contributor to the Truthout anthology, Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? In 2014 and 2017, Project Censored featured Ludwig’s reporting on its annual list of the top 25 independent news stories that the corporate media ignored. Follow him on Twitter: @ludwig_mike.

Truthout publishes a variety of hard-hitting news stories and critical analysis pieces every day. To keep up-to-date, sign up for our newsletter by clicking here!

Spread the word