President Trump’s 2020 budget, released today, would make poverty more widespread, widen inequality and racial disparities, and increase the ranks of the uninsured. It would also underfund core public services and investments in areas that are important for long-term growth, both in 2020 and for the next decade. And at the same time that it calls for these extensive budget cuts reportedly out of concern for the deficit, it provides costly tax cuts tilted to those at the top. The budget’s major themes are clear — and disturbing.

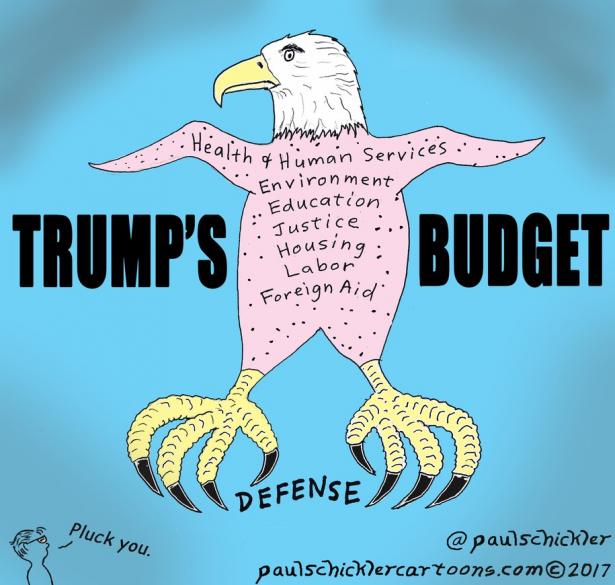

The budget proposes deep cuts in non-defense discretionary (NDD) programs alongside sizeable defense increases, which it would fund through a massive budget gimmick. NDD programs, funded through annual appropriations, range from education and veterans’ medical care to environmental protection, low-income housing assistance, child care, national parks, and international affairs. The Trump budget proposes cutting fiscal year 2020 NDD funding by $54 billion (9 percent) below the 2019 level, and by $69 billion (11 percent) after adjusting for inflation. These cuts hold NDD funding to the cap set by the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 and subsequently lowered through sequestration.

For most NDD programs, the cuts would be even deeper than these overall figures suggest, because the budget protects some programs from cuts and raises funding for others. For example, it increases discretionary funding 15 percent for the Department of Homeland Security and 7 percent for Veterans Affairs, while cutting funding by 12 percent for Health and Human Services, 18 percent for Housing and Urban Development, and 31 percent for the Environmental Protection Agency.

Cuts of this magnitude inevitably entail substantial reductions in various programs that strengthen long-term economic growth or that assist workers and low-income households, such as education, job training, and housing. In many cases, such as infrastructure (discussed below), the budget presents a one-sided view by highlighting selected program increases while downplaying cuts in related programs.

The budget calls for still deeper cuts in the years after 2020. In 2029, the budget would set overall NDD funding about 40 percent below funding in 2019 adjusted for inflation. Either the Administration knows that cuts of this magnitude are highly unrealistic, in which case their claims of deficit reduction are overblown, or it foresees a nation sharply curtailing much of what it does, from maintaining national parks to investing in education.

In defense — as in NDD — adhering to the BCA’s cap for 2020 would require steep cuts. But the budget proposes to circumvent the defense cap by providing large additional funding outside the cap. It would do so by dramatically increasing funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), a budget category that covers war costs and is exempt from the caps. The budget’s $165 billion for OCO in 2020 is almost two-and-a-half timesthe $69 billion enacted for OCO in 2019. The additional OCO funding would support core defense activities, violating the spirit and intent of the BCA. The net result of adhering to the defense cap but increasing OCO by $96 billion would be to raise overall defense funding by $34 billion or 5 percent.

The President’s budget departs sharply from the most recent bipartisan budget agreement, reached in early 2018, which eliminated the sequestration cuts for 2018 and 2019 in defense and non-defense and added funding for priority investments in both areas, reflecting bipartisan recognition that the BCA’s post-sequestration caps are too low to meet national needs in either area. The additional NDD funds paid for investments in areas such as child care, infrastructure, and opioid addiction prevention and treatment.

Even with these new investments, NDD spending in 2019 stands at only 3.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), a historically low level. And the President’s budget would hold NDD funding to the post-sequestration levels, which Congress rejected for 2018 and 2019 (and, in fact, for every year since the sequestration cuts were first slated to take effect). By 2021, NDD spending under the budget would be lower, as a share of the economy, than in any year since the Hoover Administration.

The budget would add millions to the ranks of the uninsured by repealing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and making deep cuts in Medicaid. It proposes cutting $777 billion over ten years from Medicaid and ACA subsidies that help people afford marketplace health coverage, primarily by repealing the ACA, including the Medicaid expansion, and replacing that coverage with an inadequate block grant, while also imposing a per-capita cap on the rest of the federal Medicaid program. These proposals would end the ACA’s nationwide protections for people with pre-existing conditions, cause millions more people to become uninsured, and increase costs and otherwise impede access to health care for millions more. The budget also includes other Medicaid cuts, such as making it harder for eligible people to obtain coverage by requiring additional documentation of citizenship or immigration status, re-imposing asset tests, and making it harder for some seniors and people with disabilities to qualify for Medicaid without selling their homes.

The budget would cut assistance that helps struggling families afford the basics, including food and rent. It targets for deep cuts benefits and services for people of modest means, even as it confers large tax cuts on those at the top. It would cut SNAP (food stamps) by $220 billion (about 30 percent) over ten years, cut basic assistance for people with disabilities through Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income, reduce supports to poor families with children through Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and eliminate the Social Services Block Grant. The budget calls for deep cuts in public housing, a critical source of affordable housing, and would raise rents for millions of low-income households receiving rental assistance (including both those living in public and private housing).

The budget also calls for policies that would take away assistance — including health care, food assistance, and housing assistance — from individuals who do not meet a work requirement. Significant evidence shows, however, that taking away assistance when individuals are not employed or enrolled in job programs does little to improve longer-term employment outcomes, while leaving many worse off when they lose needed assistance. According to a recent report from the National Academy of Sciences, “It appears that work requirements are at least as likely to increase as to decrease poverty.” That has been the case recently in Arkansas, the one state that has implemented a Medicaid waiver that takes away coverage from individuals not meeting a work requirement; as of January, more than 1 in 5 of those subject to the new policy had lost Medicaid, while only a few hundred had newly gained jobs or increased their work hours. The President’s budget proposal, when fully in effect, would cut the number of people receiving Medicaid by roughly 1.7 million people, based on the Administration’s own estimates of the resulting budget savings.

The budget likely shrinks funding for infrastructure over time. Although the budget proposes $200 billion in new mandatory funding for infrastructure, cuts in other infrastructure funding over time would likely outstrip its short-run funding increase. For example, the budget assumes large cuts in Highway Trust Fund spending after 2021. Although details are still emerging, the documents released today also show cuts to discretionary funding that supports infrastructure spending on priorities such as housing, transportation, and environmental protection and remediation.

The budget’s tax cuts and program changes would increase income inequality and widen racial disparities. The budget would permanently extend the 2017 tax law’s tax cuts for individuals, including those that confer large tax benefits on high-income taxpayers and heirs to very large estates. This would cost $275 billion in 2028 alone, the Congressional Budget Office estimates. Together with the budget’s proposed cuts in Medicaid, SNAP, TANF, and low-income discretionary programs, these policies would worsen income inequality.

Moreover, because of historical and ongoing discrimination and unequal educational opportunities, households of color would lose disproportionately from this combination of tax cuts and program cuts, which would shift resources to those who already have high incomes or substantial wealth. The biggest winners from the 2017 tax law were non-Hispanic white households in the top 1 percent — who receive more tax-cut dollars from it than the bottom 60 percent of households of all races. In addition, the budget’s proposed cuts in SNAP, Medicaid, and other low-income programs would disproportionately hit Black and Latino households who would get little or no benefit from extending the tax cuts.

End Notes

The defense total includes $9 billion funding that the Administration has designated as emergency requirements.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty,Washington: The National Academies Press, 2019, p. S-12, https://www.nap.edu/read/25246/chapter/2#12.

Jennifer Wagner, “Medicaid Coverage Losses Mounting in Arkansas from Work Requirement,” CBPP, January 17, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/medicaid-coverage-losses-mounting-in-arkansas-from-work-requirement.

Roderick Taylor, “ITEP-Prosperity Now: 2017 Tax Law Gives White Households in Top 1% More Than All Races in Bottom 60%,” CBPP, October 11, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/itep-prosperity-now-2017-tax-law-gives-white-households-in-top-1-more-than-all-races-in-bottom.

Paul N. Van de Water is a Senior Fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, where he specializes in Medicare, Social Security, and health coverage issues. He is Director of Policy Futures.

Joel Friedman is Vice President for Federal Fiscal Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), where he specializes in U.S. federal budget and tax issues, and a Senior Fellow at the International Budget Partnership (IBP), where he focuses on budget transparency and accountability in countries around the world.

Sharon Parrott is a Senior Fellow and Senior Counselor at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Parrott brings to the Center’s leadership team deep expertise in poverty and economic opportunity as well as the federal budget and low-income programs and will help advance the Center’s priorities across a range of policy areas.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.

Spread the word