Duke Ellington leads his orchestra in a rehearsal in Coventry, England, on Dec. 2, 1966. Associated Press

Michelle R. Scott, University of Maryland, Baltimore County and Earl Brooks, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

At a moment when there is a longstanding heated debate over how artists and pop culture figures should engage in social activism, the life and career of musical legend Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington offers a model of how to do it right.

Ellington was born on April 29, 1899 in Washington, D.C. His tight-knit black middle-class family nurtured his racial pride and shielded him from many of the difficulties of segregation in the nation’s capital. Washington was home to a sizable black middle class, despite prevalent racism. That included the racial riots of 1919’s Red Summer, three months of bloody violence directed at black communities in cities from San Francisco to Chicago and Washington D.C.

Ellington’s development from a D.C. piano prodigy to the world’s elegant and sophisticated “Duke” is well documented. Yet a fusion of art and social activism also marked his more than 56-year career.

Ellington’s battle for social justice was personal. Films like the award-winning “Green Book” only hint at the costs of segregation for black performing artists during the 1950s and 60s.

Duke’s experiences reveal the reality.

Ellington and his Cotton Club Orchestra playing ‘The Mooche,’ 1928.

Cotton Club to Scottsboro Boys

Ellington first rose to fame at Harlem’s “whites only” Cotton Club in the 1920s. There, the only mingling of black and white happened on the piano keyboard itself, as black performers entered through back doors and could not interact with white customers.

Ellington quietly devoted his services to the NAACP and its racial equality activities in the 1930s. Whether it was demanding that black youth have equal entrance rights to segregated dance halls or holding benefit concerts for the Scottsboro Boys, nine black adolescents falsely imprisoned for rape in 1931, Ellington used his growing fame as a prominent band leader for a greater good.

In our literary and historical research on African American entertainment, Ellington’s ability to travel and perform across national boundaries stands out.

After success in Harlem’s night spots, Ellington composed, recorded and appeared in film shorts like 1935’s “Symphony in Black” as himself. He traveled the world with his orchestra, at first performing in the U.K. in the 1930s. Later, Ellington continued to perform on behalf of the U.S. State Department as a “jazz ambassador” in the 1960s and 70s. Audiences in such places as India, Syria, Turkey, Ethiopia and Zambia were given the opportunity to hear and dance to Ellington’s compositions.

However, not even international popularity ensured that hotels would host Ellington’s all-black ensemble during a tour in the U.K. in June 1933. Members scrambled to find boarding homes in London’s Bloomsbury neighborhood when mainstream hotels turned them away on account of their race.

Despite success, racism

Ellington’s 1932 “It Don’t Mean a Thing if It Ain’t Got That Swing” was the soundtrack for the nation’s swing era of the 1930s and 40s. The tune stayed on the Billboard charts for six weeks in 1932 and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2008.

But when Ellington traveled in the South, he still had to hire a private rail car to avoid crowded, poorly maintained “colored only” train seating, or hotels and restaurants that refused service to black Southerners.

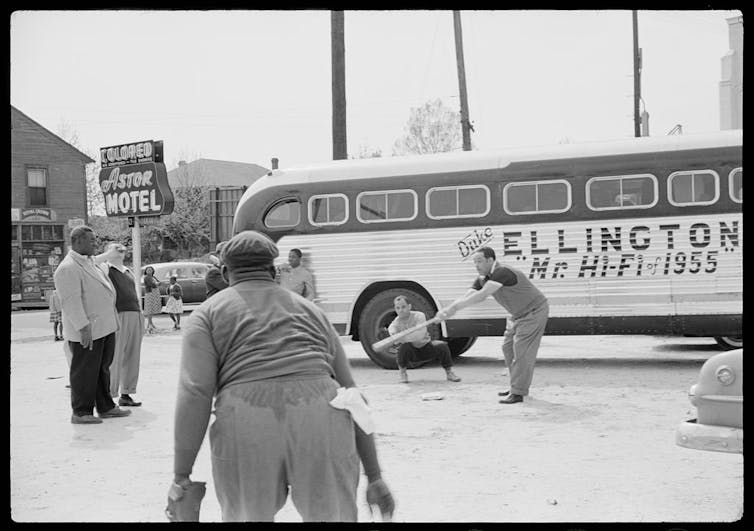

Ellington and band members playing baseball in front of the ‘colored’ only Astor Motel while touring in Florida in 1955. Library of Congress/Charlotte Brooks photographer

Northern or western engagements in the 1930s and 1940s often proved no better. While there were no “white only” signs on the doors of these hotels or restaurants, establishments enforced segregation by telling black customers to enter through back doors or purchase their meals to go.

Bassist Milt Hinton recalled that Ellington and fellow band leader Count Basie often stayed at black-owned boarding houses rather than risk being thrown out or ignored.

White band managers attempted to protect the black bands they managed from these racist practices, but this still did not prevent Ellington from being denied service in a Salt Lake City hotel’s cafe in the 1940s.

Subtle style

Once the civil rights movement of the 1950s began to fight for racial equality through direct-action techniques like mass protests, boycotts and sit-ins, activists in the early 1950s criticized the older Ellington. His subtle activism style had focused on benefit concerts, and not “in the streets” protests.

But as the movement continued, Ellington included a non-segregation clause in his contracts and refused to play before segregated audiences by 1961. He maintained in an interview in the Baltimore Afro American newspaper that he had always been devoted to “the fight for first class citizenship.”

This was a devotion best seen in his music.

Ellington used his creative musical talents against racist beliefs that African Americans were inferior or unintelligent.

His diverse and wide-ranging catalog of music demanded the kind of serious attention and respect that had previously only been reserved for elite, white composers of classical music.

Songs such as “Black and Tan Fantasy” completely challenged what was then called “jungle music,” a negative term used to reference music inspired by the African diaspora. As a fusion of sacred and secular black culture, both the “Black and Tan Fantasy” composition and film combined the speaking traditions of black preachers with the humor and rhythms of black life.

‘Black and Tan Fantasy’ melded sacred and secular black culture.

Modern black variety shows such as “Wild ‘N Out” and “In Living Color” share a lineage with Ellington’s major stage production of 1941, “Jump for Joy.”

“Jump for Joy” combined comedy skits and music into a revue that featured African American stars of the mid-20th century, including actress, singer and dancer Dorothy Dandridge and poet Langston Hughes.

Ellington claimed that his production “would take Uncle Tom out of the theater and say things that would make the audience think.”

He used his music to showcase black excellence as a resistance tactic against the negative stereotypes of African Americans made popular in American blackface minstrelsy.

Ellington also used “Jump for Joy” to call out those who borrowed from black music without any credit or financial compensation to its creators.

Duke Ellington, Paramount Theater, New York, 1946. Library of Congress/William P. Gottlieb photographer

Melody’s other purpose

One of Ellington’s most powerful works is the orchestral piece “Black, Brown and Beige.”

This work shows his ability to infuse the blues into classical music and his commitment to tell the history of black America through song.

From the spirituals developed through the trials of slavery to the fight for civil rights and the modern rhythms of big band swing music, Ellington sought to tell a story about black life that was both beautiful and complex.

For Ellington, melody became message.![]()

Michelle R. Scott, Associate Professor of History, University of Maryland, Baltimore County and Earl Brooks, Assistant Professor of English, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Spread the word