Democracy, they say, is in crisis. The Washington Postran a Super Bowl ad warning us that “Democracy Dies in Darkness.” Political scientists Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky have published a book titled How Democracies Die. And Larry Diamond, éminence grise of democracy scholarship, has diagnosed a global democratic recession.

It is not my aim to pour cold water on these kinds of concerns. There is much in recent history to fret about. Yet a single-minded focus on contemporary events can mislead. In studying only today’s backsliding, we risk ignoring the forest for a few Trump-shaped trees.

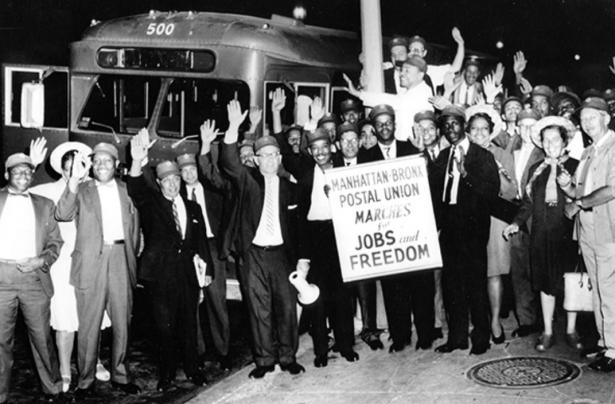

To understand democracy — to defend it and to deepen it — we should examine its long history rather than obsess about recent headwinds. In a recent article published in the American Journal of Sociology, I attempt to do just that. My research suggests that democratic progress over the last 150 years is the fruit of the changing character of class struggle over the state. Democracy has its origins in the capacity of the poor to disrupt the routines of the rich.

It is not wrong to worry, as many do, about new ideas, institutions, and ideologues. But history teaches us that the task of saving democracy is in large part the task of reviving the disruptive capacities of ordinary people.

The Democratic Transition

One need not be Pangloss (or Steven Pinker) to note that the rise of democracy has transformed the world. At the heart of this ascent lies a paradox. Democracy, after all, introduces equality into societies riven by class and status hierarchy. To our ancestors, there would have been nothing stranger than learning that kings and lords would soon cede power to their serfs. Yet steadily, our unequal world democratized. Our best indicators record extraordinary, mostly steady progress since the French Revolution.

Why is this? What changed? One answer is that politics changed because our ideas about politics changed. Steven Pinker argues something like this in his recent history of human progress. Democracy, he suggests, emerged once Reason took charge of human affairs.

An obvious problem with this argument is that it answers one question only to raise another. If democracy emerged because our ideas about liberty and equality changed, why did our ideas change?

For a long time, the most common answer to the democratization puzzle was that democracy was the result of economic growth. There was always some disagreement about why — some argued economic development yielded a tolerant middle class, others believed a complex economy demanded a complex polity — but the general view was that modernization brought democracy in train.

Recent work has challenged this view. While richer countries are indeed more democratic, it is not clear that countries democratize as they develop. Economic expansion may entrench elites as much as it topples them. The modernization view has given only passing thought to the protagonists and villains of the democratic transition. Who demands democracy from whom? And under what conditions are they most likely to succeed?

The Class Struggle Over the State

In seeking to answer these questions, economists and political scientists have conceived of the battle over democracy as a struggle between the rich and poor over the state. The rich, who are a minority, fear political equality. The poor, who are numerous, pine for it.

These authors are right to assume that democratization is a contest between contending classes over the state. Yet they have mostly misunderstood the character of this contest. Specifically, they have misunderstood the conditions under which the poor win democracy from the rich. The leverage of the poor comes not from growing wealth (as Ben Ansell and David Samuels argue) or from the threat of an unexpected rebellion (as Damon Acemoglu and James Robinson or Carles Boix claim). Rather, their leverage is the result of economic developments that give the poor the capacity to challenge the routines on which elites depend for their wealth.

To appreciate this, we need only observe a few basic facts about the economy and the state.

First, in any inegalitarian society, the state will show deference to the rich over the poor — even if the state is not staffed by representatives of the rich. The reason is simple: The state depends on a healthy economy to yield the revenues it requires for its own aims. And because the health of the economy is a function of the health of investment, those who own the economy’s commanding heights have disproportionate influence over the state.

Of course, the poor can also disrupt economic life. But because their only asset is their capacity to work, they cannot exercise power as individuals, unlike the rich. To disrupt economic life, they must coordinate with others. Since collective action is much more difficult than individual action, the rich will always have more power over the state than the poor.

Second, this balance of disruptive capacities, while always unequal, is not stable. The capacity of any given poor person is a function of the work they do. Some poor people have greater leverage over economic life, whether because they work in key industries or because they have relatively scarce skills. Others find it easier to coordinate collective action because they work in large, densely clustered workplaces.

Critically, economic development creates new roles for the poor to fill (and thus, different forms of dependence of the rich on the poor). It also shifts the distribution of the poor across existing roles. In doing so, it transforms the balance of disruptive capacities between rich and poor. Sometimes, these transformations narrow the gap in aggregate capacities between rich and poor. When this happens, the poor acquire influence over the state.

What does this imply for the fate of democracy? Quite simply, where ordinary people accumulate the ability to disrupt the economy, we should expect to see progress towards democracy.

In my paper I tested this hypothesis quantitatively, using the share of the working-age population employed in the historic redoubts of the labor movement (manufacturing, mining, construction, and transport) as a measurement for the disruptive power of ordinary people. I drew on data spanning dozens of countries over much of the modern period.

My estimates suggest that ordinary people’s ability to disrupt the normal workings of the economy is a significant, powerful predictor of patterns of democratization over time. All else equal, as a country’s working-age population clusters in these industries, so grows the quality of democracy in that country.

Separately, I found that, as others have also shown, one of the key obstacles to democratization is the existence of a strong landlord class. Landlords are particularly threatened by democratization because they often depend on antidemocratic institutions to maintain their workforce (like coercive labor arrangements) and because their assets are fixed in place. Historically, large landowning classes have thus been hostile to even formal democratic arrangements.

To observe that the class struggle over the state drives democratization is not to argue that nothing else matters. I found some evidence that democracy is more likely when a country’s neighbors are also democratic, that more unequal countries are more likely to democratize, and that education incubates democracy. But the most consistent, powerful explanations for the rise of democracy are these two: the growth of the disruptive capacities of ordinary people and the death of the landlord class.

Defending Democracy Better

For the big questions that worry scholars and citizens today, this history has some important, abiding lessons.

Most importantly, we should never forget that democracy is the awesome task of bending the powerful to the public interest. Because economic inequality gives its beneficiaries the tools to undermine political equality, there will always be something unavoidably difficult about defending democracy in an inegalitarian order. Some fraction of democracy’s present-day woes may be the result of the rise of new media or particularly able demagogues. But at its core, our problem is an ancient one.

And so, in aiming to defend and deepen democracy, we should hold on to the story of its origins. The history of democracy is the history of the struggle between rich and poor over the state. To defend it, we must defend the ability of the poor to challenge the rich.

Spread the word