books A Son’s Memoir of His Father’s Radical Beliefs, Pursuit by the F.B.I. and Ardent Love for America

“Think of this story as a wheel,” David Maraniss writes in an author’s note at the beginning of his new book, “A Good American Family.” “The hearing in Room 740 is the hub where all the spokes connect.”

Room 740 in Detroit’s Federal Building was where Maraniss’s father, Elliott, was summoned to appear before the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) one day in 1952, to answer charges that he was a member of the Communist Party. Simply being subpoenaed to appear had already cost Elliott his job, and his refusal to cooperate with the committee’s questions would force him into years of desperate struggle to keep his family afloat.

Elliott Maraniss was no atomic spy or government mole. He was a rewrite man at The Detroit Times, a World War II vet with a wife and three kids. HUAC had come to Detroit hoping to find communists in the United Auto Workers, a powerful liberal institution; people such as Elliott and his wife’s brother, Bob Cummins, were just “collateral damage,” expected to make “a few acts of repentance and contrition” — bow their heads and name names of old friends and comrades in the ongoing theater of the Red scare. If they didn’t, they were dismissed after a brief interrogation with their lives in tatters. Elliott was not even permitted to read a prepared statement, though he was allowed to file it with the committee.

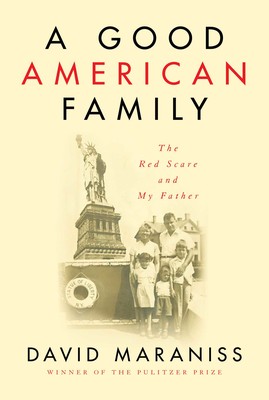

A Good American Family: The Red Scare and My Father

By David Maraniss

Simon and Schuster; 416 pages

Hardcover: $28.00; E-book: $14.99

May 14, 2019

ISBN: 9781501178375

Now, David Maraniss, in his “long overdue attempt to understand what had happened to my father and our family and the country during what has come to be known as the McCarthy era,” has unearthed that statement, and that moment. A winner of two Pulitzer Prizes in journalism and one of our most talented biographers and historians, Maraniss has used his prodigious research skills to produce a story that leaves one aching with its poignancy, its finely wrought sense of what was lost, both in his home and in our nation. It is at the same time a book that, like his family, never gives in to self-pity but remains remarkably balanced, forthright and unwavering in its search for the truth.

David’s father was “a liberal but undogmatic optimist,” whose mantra was “It could be worse.” He loved baseball and literature and funny songs; he once wrote a column under the moniker “the Ol’ Railbird”; and he had an abiding passion for nearly everything to do with the American heartland. He was, his son tells us, a brilliant newspaperman but also a constant “force for good … not only in my life and those of my siblings,” but also in the lives of everyone he knew.

So how does such a man end up writing Soviet propaganda under a fake name for The Michigan Worker? “I can appreciate his motivations, but I am confounded by his reasoning and his choices,” Maraniss confesses.

Elliott was the son of Jewish immigrants from Odessa and Latvia, a Boy Scout who grew up in Coney Island, an outstanding student and editor of the school paper at Abraham Lincoln High School — a place almost painful to behold in its glowing idealism and dedication to learning, even in the midst of the Depression. A fellow student was Arthur Miller, whose own encounters with communism and the Red scare are another “spoke” connected to Room 740. Like Miller, Elliott went on to the University of Michigan, then “in one of its own golden periods” of scholarship, where he discovered his great love for the Midwest.

He also encountered a key influence on his political development: 17-year-old Mary Cummins, a wisp of a girl with strawberry blond hair and deeply held radical convictions. The Cumminses were another remarkable American family, originally dirt-poor Kansas homesteaders living in a one-room dugout cut out of a hillside. Mary’s father was a civil engineer who couldn’t afford to finish his degree, but made enough money to drive a Cadillac and send his five children to college. The courtship of Elliott and Mary included strolls through Ann Arbor to gaze at a “little blue house on Stadium Boulevard” they dreamed of owning one day. Throughout their long marriage Mary insisted on buying the homes the family lived in — strange behavior for an avowed communist.

By 1939, as editorial director of The Michigan Daily, Elliott was defending the monstrous Stalin-Hitler pact that triggered World War II — a stance that outraged and mystified many of his readers and friends, as well as his son, who calls it one of Elliott’s “indefensible positions.” When the war reached the United States, Stalin was back on the side of the Allies and both Maranisses threw themselves into the struggle. Elliott enlisted, while Mary helped build B-17s, and advocated for civil rights at her plant.

Rising to the rank of captain, Elliott was put in charge of a black salvage-and-repair company in the still segregated Army, arriving in Okinawa in July 1945, just after the terrible battle there. He excelled in his position, and the experience seemed to fill him with patriotic ardor. He wrote passionately to his wife about Franklin Delano Roosevelt, General MacArthur and especially Dwight Eisenhower, whom he would later admit to having voted for in 1952. He always harbored, it seemed, a desire to belong to a wider America, even as he saw its shortcomings.

Unbeknown to Elliott, though, his assignment to command black troops was the end result of a desire by military intelligence, wary of his “communistic” tendencies, to exclude him from sensitive work while in the Army. Before his file was finally sealed, some 14 F.B.I. agents would interview 39 “confidential informants” about him. Their investigation would culminate in Room 740, but it would not end there. Even after HUAC had finished with him, the F.B.I. sent agents to interview Elliott’s employers whenever he got a job, knowing it would likely cost him the position. The consequence was a series of agonizing sojourns back and forth across the country, as Elliott sought to find and keep gainful employment, badly straining his family and his nerves.

“A Good American Family” is intercut with Maraniss’s deep dives into the lives and backgrounds of all those other “spokes,” before, during and after the hearing in Room 740 — an effort to explore one congressman’s amazement that even some communists hailed from “good American families.” Here are his father’s radical friends who went to fight (and die) in Spain, along with his lawyer, fellow witnesses, the professional informer — a five-foot grandmother and high school dropout — who had ratted out Elliott, along with the prosecutor and leading inquisitors on the committee. Maraniss is able to spare some sympathy for the corrupt, drunken Democratic chairman of HUAC at the time, Representative John Stephens Wood, an inveterate racist with an appalling secret in his past — whose society wife would have little to do with him after she discovered his Cherokee ancestry.

This is, in the end, a fascinating confluence of America, and if the story drags in places — we don’t really need to know that there were 17,000 varieties of American apple by 1905 — more often one is bowled over by the vibrancy of that vanished nation. It’s a world where David’s sister listens to a new song called “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” and the family watches mesmerized as exquisite lines of Detroit cars appear every summer. Elliott’s wanderings take him to an Iowa newspaper that grew out of a strike by union typographers. Later, he sees his revered new publisher, William T. Evjue of The Capital Times, in Madison, talking and laughing in his office with Carl Sandburg and Frank Lloyd Wright. Did we ever live in such an America? Did we just dream it?

After a long travail, Elliott and Mary Maraniss and their children would come through, buoyed by their unflagging optimism and faith. (Remarkably, the book’s cover photo, of the Maranisses posing in front of the Statue of Liberty, was taken after Elliott’s ordeal in Room 740.)

For all of Maraniss’s research, a mystery remains at the heart of “A Good American Family”: Just what were his parents, and especially his father, doing in the Communist Party in the first place? This is a question Maraniss cannot answer, because his parents, for one reason or another — shame? embarrassment? an effort to spare their children? — rarely spoke of it. About the furthest his father would go was to admit that he had been “stubborn in his ignorance about the horrors of the Soviet Union.” But this gives us little insight into how this great American spirit ended up stuffing himself into a closet of dreary Russian dogma.

In the end, even in the best of families, some things remain secret.

Book author David Marannis is an associate editor at The Washington Post and a distinguished visiting professor at Vanderbilt University. He has won two Pulitzer Prizes for journalism and was a finalist three other times. Among his bestselling books are biographies of Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Roberto Clemente, and Vince Lombardi, and a trilogy about the 1960s – Rome 1960; Once in a Great City (winner of the RFK Book Prize); and They Marched into Sunlight (winner of the J. Anthony Lucas Prize and Pulitzer Finalist in History). A Good American Family is his twelfth book.

[Essayist Kevin Baker is a New York-based writer and editor. His first novel, Sometimes You See It Coming (1993) is, based loosely on the life of Ty Cobb. Dreamland (1999), part of Baker’s New York‚ City of Fire trilogy was followed by Paradise Alley (2002), and succeeded shortly by Strivers Row (2006.) Baker was the chief historical researcher on Harold Evans’ history, The American Century, wrote the monthly “In the News” column for American Heritage magazine from 1998-2007, and has been published in The New York Times, The New Republic, Politico.com, New York magazine, The Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, The Los Angeles Times, The Frankfurter Rundschau, and Harper’s magazine, among other publications. He is currently finishing a book on the history of New York City baseball.]

Spread the word