On Feb. 24, 2016, after winning the Nevada caucuses, Donald Trump told supporters in Las Vegas, “I love the poorly educated.”

Technically, he should have said “I love poorly educated white people,” but his point was well taken.

We have been talking about this since Trump came down that escalator four years ago, but we haven’t quite reckoned with the depth of the changes in the electorate or the way they have reshaped both parties.

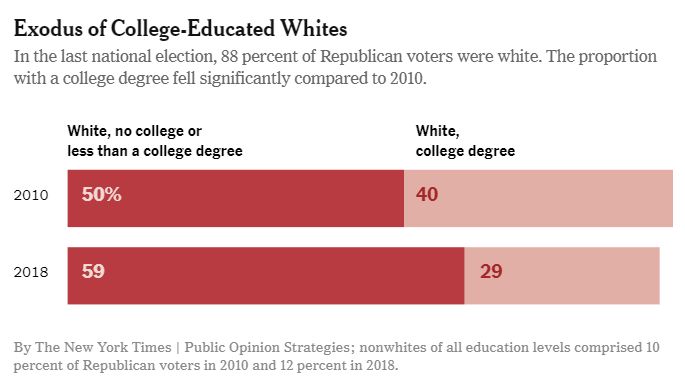

Take a look at this graphic of the changing makeup of the Republican electorate based on NBC/Wall Street Journal poll data provided by Public Opinion Strategies.

In less than a decade, from 2010 to 2018, whites without a college degree grew from 50 to 59 percent of all the Republican Party’s voters, while whites with college degrees fell from 40 to 29 percent of the party’s voters. The biggest shift took place from 2016 to 2018, when Trump became the dominant figure in American politics.

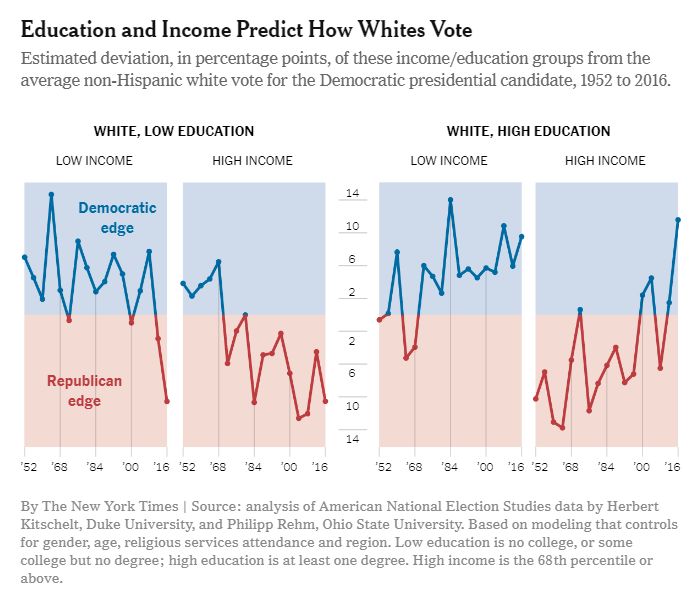

This movement of white voters has been evolving over the past 60 years. A paper published earlier this month, “Secular Partisan Realignment in the United States: The Socioeconomic Reconfiguration of White Partisan Support since the New Deal Era,” provides fresh insight into that transformation.

The authors, Herbert Kitschelt and Philipp Rehm, political scientists at Duke and Ohio State, make the argument that the transition from an industrial to a knowledge economy has produced “tectonic shifts” leading to an “education-income partisan realignment” — a profound realignment of voting patterns that has effectively turned the political allegiances of the white sector of the New Deal coalition that dominated the middle decades of the last century upside down.

Driven by what the authors call “first dimension” issues of economic redistribution, on the one hand, and by the newer “second dimension issues of citizenship, race and social governance,” the traditional alliances of New Deal era politics — low-income white voters without college degrees on the Democratic Party side, high-income white voters with degrees on the Republican side — have switched places. According to this analysis, these two constituencies are primarily motivated by “second dimension” issues, often configured around racial attitudes, which frequently correlate with level of education.

Perhaps most significant, Kitschelt and Rehm found that the common assumption that the contemporary Republican Party has become crucially dependent on the white working class — defined as whites without college degrees — is overly simplistic.

Instead, Kitschelt and Rehm find that the surge of whites into the Republican Party has been led by whites with relatively high incomes — in the top two quintiles of the income distribution — but without college degrees, a constituency that is now decisively committed to the Republican Party.

According to the census, the top two income quintiles in 2017 were made up of those with household incomes above $77,552. More than half of the voters Kitschelt and Rehm describe as high income are middle to upper middle class, from households making from $77,522 to $130,000 — not, by contemporary standards, wealthy.

Kitschelt and Rehm write:

Individuals in the low-education/high-income group tend to endorse authoritarian noneconomic policies and tend to oppose progressive economic policies. Small business owners and shopkeepers — particularly in construction, crafts, retail, and personal services — as well as some of their salaried associates populate this group.

In an email, Kitschelt elaborated:

Unlike much of the current debate, the ‘white working class’ — concentrated in the low-education/low-income sector of the white population — is not the category that has most ardently realigned toward Republicans. It’s higher income/low education whites who are currently still doing well, but fear that in the Knowledge Society their life chances are shrinking as high education becomes increasingly the ticket to economic and social success.

Low-income whites without college degrees have moved to the Republican Party, but because they frequently hold liberal economic views — that is, they support redistributionist measures from which they benefit — they are conflicted in their partisan allegiance.

The authors point out that members of this group

tend to support progressive economic policies and tend to endorse authoritarian policies on the noneconomic dimension. In occupational terms, this group consists primarily of low-skill and intermediate routine blue-collar manufacturing or clerical-administrative jobs (the ‘working class’).

One key to Trump’s success with contemporary voters, the authors note, is that his repeated campaign promise to protect Medicare and Social Security put him on the side of core adherents of the welfare state.

“What is noteworthy,” Kitschelt and Rehm write, is that most voters

perceived the Republicans’ 2016 presidential candidate Donald Trump as substantially more moderate than his party, and as more moderate than most Republican presidential candidates since 1980.

For Democratic voters who switched to Trump in 2016, “this perception would have removed cognitive dissonance and inhibitions” that would have prevented them from supporting an economic conservative in the mold of Mitt Romney. Freed of that inhibition, they could vote for Trump, Kitschelt and Rehm argue, “based on socio-politically authoritarian, and often racist, positions that were served by Trump’s rhetoric.”

In the 1950s and 60s, low-income whites without degrees formed the base of the Democratic Party; now this group leans Republican. In 1952, they made up 49.6 percent of all whites in the electorate; in 2016, their share fell to 39.7 percent.

High-income whites without college degrees were swing voters sixty years ago, pursued by both parties; now, they are rock-ribbed Republicans. Their share of the white electorate has fallen, however, from 42.1 to 22.0 percent.

Two generations ago, there were almost no low-income whites with college degrees, a group that made up 1.5 percent of white voters in 1952. These voters were a swing bloc without firm commitment to either party. By 2016, this constituency had grown to form 14.3 percent of all voters. They have, in turn, become the most loyal white Democratic constituency.

In the 1950s, high-income whites with college degrees were the base of the Republican Party — although in 1952 they made up just 6.7 percent of white voters. By 2016, this cohort had moved decisively toward the Democratic Party, as its share of the white electorate had grown to 26.0 percent.

Kitschelt and Rehm track the shifting voting patterns of whites in the accompanying graphic.

Kitschelt and Rehm separately provided data on the rates of union membership among the various categories of white voters. The data points to the devastating consequences of declining union membership for the Democratic Party.

Non-college whites, both low- and high-income, were heavily unionized in the 1950s and 1960s, when both groups cast majorities for Democratic presidential candidates. Over time, each group has experienced a precipitous decline in union membership.

Among those with low incomes, the level of unionization fell from 22.7 in 1952 to 13.0 percent in 2016. Among those with high incomes, the rate of unionization dropped from 38.9 to 19.6 percent.

The election of Donald Trump has prompted a groundswell of studies of white voters.

The key bloc for both Trump and the Republican Party is made up of white Christian evangelicals. Eight out of ten of these voters cast ballots for Trump, and intensely religious voters make up 40 percent of the Republican electorate.

Emily Ekins, director of polling at the libertarian Cato Institute, argues in her paper “Does Religious Participation Moderate Trump Voters’ Attitudes about Diversity?” that white evangelical Christian Trump voters are substantially more moderate on issues of race and diversity than less religious Trump voters. At the same time, Ekins argues, the partisanship of these religious voters is stronger than their self-described moderate racial views, and their loyalty to Trump remains unshakable.

Ekins documents her assertions with polling from 2016, 2017 and 2018 conducted by the Democracy Fund’s Voter Study Group. These polls show, for example, that 74 percent of Trump voters who attend church weekly or more often report warm feelings toward black Americans, compared with 48 percent of Trump voters who never attend services. Nine percent of churchgoing Trump voters said their white identity was “extremely important to them” compared with 26 percent of those who never go to church. The same patterns emerge on questions concerning diversity, immigration and attitudes toward Muslims and Hispanics.

In a reflection of the complexity of the effort to analyze Trump’s white support, Paul A. Djupe and Ryan P. Burge, political scientists at Denison University and Eastern Illinois University, have challenged Ekins. They argue that the seeming racial moderation of white evangelical voters is superficial, far less important to them than their partisan commitment to Trump and the Republican Party.

“Why are religious Trump voters showing more support for Trump when they hold more liberal attitudes?” Djupe and Burge ask. Because, they argue, “partisanship is their core value and all else is secondary, including their religion.”

In their critique of Ekins study, Djupe and Burge suggest that the racially moderate views of churchgoers

may capture socially desirable representations and do not reflect their true attitudes. While it is possible that they are simply dissembling, religious congregations exert considerable pressure on attenders to conform to a set of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors.

In a more telling critique, Djupe and Burge examined the small fraction of Trump voters who by 2018 reported that they had “regrets” about voting for him:

If so many Trump-supporting church attenders have liberal outlooks on politics and toward politically salient groups, they should be more likely to express regrets for their vote for Trump.

Instead, the exact opposite happened:

As their warmth toward minorities climbs, the proportion expressing regret drives to zero among frequent church attenders. Only among those who never attend church do we see the expected relationship — warmth toward minorities drives up regret for voting for Trump.

I asked Ekins about the Djupe and Burge analysis, and she replied by email:

The strong support for Trump among religious conservatives at first may seem perplexing. But, it’s not entirely surprising given what we know about religious conservatives’ higher levels of partisan loyalty and the impact of partisanship on opinion.

Trump voters who attend church once a week or more, Ekins noted, “are much more likely than those who do not attend regularly to identify as a ‘strong Republican.’ ” Partisanship, she continued, “can outweigh even core values” and “clearly seems to be playing an important role in explaining evangelicals’ support for Trump.”

Trump supporters celebrating at a caucus-night watch party in Las Vegas in 2016. Credit Ethan Miller/Getty Images

Ekins provided poll data showing that 43.4 percent of Trump voters who go to church weekly identify as “strong Republicans,” while 34.3 percent of those who seldom go to church and 26.3 percent of those who never go identify as strong Republicans.

Closely allied to the work of Ekins, Djupe and Burge is research seeking to answer a recurring pair of questions in political science: how to measure racial prejudice and how to assess the role race prejudice plays in American elections. For example, are the voters who Djupe and Burge report as having “racially moderate views” primarily presenting “socially desirable” versions of their beliefs, or are they more genuinely without race prejudice?

In 1981, political scientists Donald Kinder and David O. Sears wrote in their widely cited paper, “Prejudice and politics: Symbolic racism versus racial threats to the good life” that there are

Two major theoretical approaches to prejudice by Whites against Blacks: realistic group conflict theory, which emphasizes the tangible threats Blacks might pose to Whites’ private lives; and a sociocultural theory of prejudice termed symbolic racism, which emphasizes abstract, moralistic resentments of Blacks, presumably traceable to pre-adult socialization.

The most widely used measures of racial resentment have come under attack from such scholars as Ryan Enos and Riley Carney, both political scientists at Harvard.

In their 2017 paper, “Conservatism and Fairness in Contemporary Politics: Unpacking the Psychological Underpinnings of Modern Racism,” Carney and Enos tested a common measure of racial resentment and described their method:

To investigate the attitudes underlying modern racism scales, we offer a novel test: we deploy surveys using the exact questions that constitute standard modern racism scales, but we substitute Blacks for other target groups that are not commonly associated with known stereotypes or overt prejudice in the United States. For example, we substitute Blacks for Lithuanians and then measure the difference between mean resentment toward Lithuanians and Blacks. Across multiple groups and multiple samples on different survey platforms, we find a strong and consistent pattern: the results obtained using groups other than Blacks are substantively indistinguishable from those measured when Blacks are the target group.

Carney and Enos see race prejudice as setting itself against the broad category of “other.” They have devised an experiment that addresses the tradition of allowing “humanity to be divided into two groups: one that embodies the norm and whose identity is valued, and another whose identity is defined by its faults, devalued and susceptible to discrimination.”

In a country as diverse and multiethnic as the United States — with so many “others” — these findings have drawn considerable attention.

Christopher D. DeSante, a political scientist at Indiana University, and Candis W. Smith, a political scientist at Penn State, have explored the use of new tools to measure racial attitudes.

In “How Racial Empathy Moderates White Identity and Racial Resentment” and “Fear, Institutionalized Racism, and Empathy: The Underlying Dimensions of Whites’ Racial Attitudes,” the authors have come up with what they call a “four-Item FIRE Scale” with FIRE an acronym for Fear, Institutionalized Racism and Empathy.

The questions ask those surveyed whether they agree or disagree with these statements:

-

I am fearful of people of other races.

-

White people in the U.S. have certain advantages because of the color of their skin.

-

Racial problems in the U.S. are rare, isolated situations.

-

I am angry that racism exists.

The authors tested the questions in a sample of more than 40,000 white voters conducted during the 2016 primary elections by the Cooperative Congressional Election Study.

They found that Trump voters, as opposed to voters supporting other Republican candidates, were “less empathetic (angered by racism), they were more likely to deny Whites have an advantage in America and expressed far more fear of other racial groups.” In addition, DeSante and Smith found that the FIRE questions proved especially effective in identifying voters who backed Obama in 2012 and switched to Trump in 2016.

In an email, Candis Smith described the advantages of the FIRE question battery:

We developed FIRE for a number of reasons. First and foremost, because while we (scholars/journalists) tend to conflate ‘racial attitudes’ with ‘racial prejudice.’ But, there’s more to it than that. There’s all sorts of feelings, attitudes, and knowledge surrounding issues of racial groups and racial inequality. FIRE aims to get at this multidimensionality. So, it’s not just that some people are resentful, but some people are fearful, some people are unaware or unwilling to be aware of (structural) racism, some people are actually empathetic about inequality. Taken together, we can say more about how the various dimensions of racial attitudes influence political attitudes/behaviors.

Exploring these dimensions, Smith continued, enables you to identify

people who are fearful of other racial groups (and you might be surprised that people are willing to admit this) were more likely to vote for Trump. So here, it’s not just “resentment” but fear that influenced people. FIRE allows us to pinpoint how both feelings (affect) and knowledge (cognition) influence people’s orientation toward politics.

Much effort has been devoted to understanding the role of race in shaping American politics over the 55 years since passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

It’s clear that all the leading Democratic presidential candidates are committed to the idea that improved race relations are crucially important. And it’s not too much to say that the future of the nation depends on arriving at a more equitable sharing of resources — tangible and intangible.

The 2020 election will be fought over the current loss of certainty — the absolute lack of consensus — on the issue of “race.” Fear, anger and resentment are rampant. Democrats are convinced of the justness of the liberal, humanistic, enlightenment tradition of expanding rights for racial and ethnic minorities. Republicans, less so. This may well prove to be a base-vs.-base election, but even so the outcome may lie in the hands of the substantial proportion of the electorate that is undecided — 7 percent according to Pew. And if Democrats want to give themselves the best shot of getting Trump out of the White House, it is toward these voters that they must make concerted efforts at pragmatic diplomacy and persuasion — and show a new level of empathy.

Thomas B. Edsall has been a contributor to The Times Opinion section since 2011. His column on strategic and demographic trends in American politics appears every Wednesday. He previously covered politics for The Washington Post. @edsall

Spread the word